A bewildering upbringing: Why Margo Perin was made to have a nose job at 13

- Published

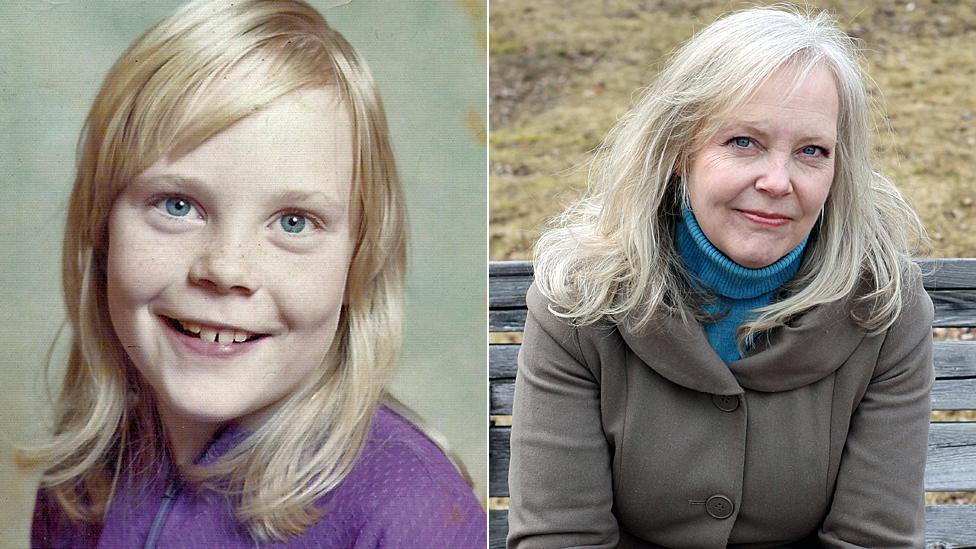

Margo at Butlins, Ayr, in 1966 or 1967

Margo Perin knew there was something dodgy about her parents - especially her violent father - but it took her years to find out what they were hiding.

Margo Perin was 13 when her father summoned her to the living room of their home in Glasgow's West End, and asked if she'd like to look prettier. He sat facing her, smoking with a shiny black cigarette holder, his gold lighter and onyx ashtray by his side. "They can do remarkable things these days," he said.

He'd taken time out from his busy schedule to visit a specialist in London, he went on, who agreed that Margo should have cosmetic surgery to reduce the size of her nose before she stopped developing. He had even made the appointment.

Margo's family before the birth of her youngest sibling, New York, 1961

Nearly everything about Margo's upbringing was traumatic and bewildering. For the first seven years of her life, Margo, her six siblings and parents lived in New York City - much of that time in a Manhattan penthouse suite. But then their life became more erratic. They adopted new surnames and uprooted themselves with unusual frequency, taking only what they could carry with them in hastily packed suitcases.

They went to live in Mexico. There, one day, their home was broken into. The place was ransacked though nothing seemed to be taken - it was as if someone had been looking for something. "How did they find us?" Margo heard her mother wailing. "No-one was supposed to know we were here." Bundled into taxis, the family was on the move again, this time to the Bahamas.

Margo's parents never explained the reason for these sudden upheavals. They rarely talked about the past either - the only clues about what was going on were the snatches of their conversations and arguments Margo overheard, in which the letters F B I would often crop up. "It was completely confusing," Margo says. "But I think what happens with children who are lied to is that they almost become like detectives."

Arden and Margo, Florida, 1963/4

Lilyan and Arden, Margo's mother and father, were very glamorous. Arden always immaculately dressed with a handkerchief in his breast pocket, shoes shined, nails manicured and hair pomaded. Lilyan had beautiful dresses and make-up, her pencilled-in eyebrows giving her a look of permanent surprise. There was a lot of cocktail-drinking, Margo remembers, and, while they lived in New York at least, her parents went out to the opera or movies almost every evening, leaving Margo's eldest sister in charge.

The children had it drummed into them that they mustn't tell anyone too much about their family life and their father even taught them a little trick to deal with any unwanted probing. If someone asks you a question that you don't want to answer, he said, you just give them another answer. "Direct questions were not encouraged," Margo says.

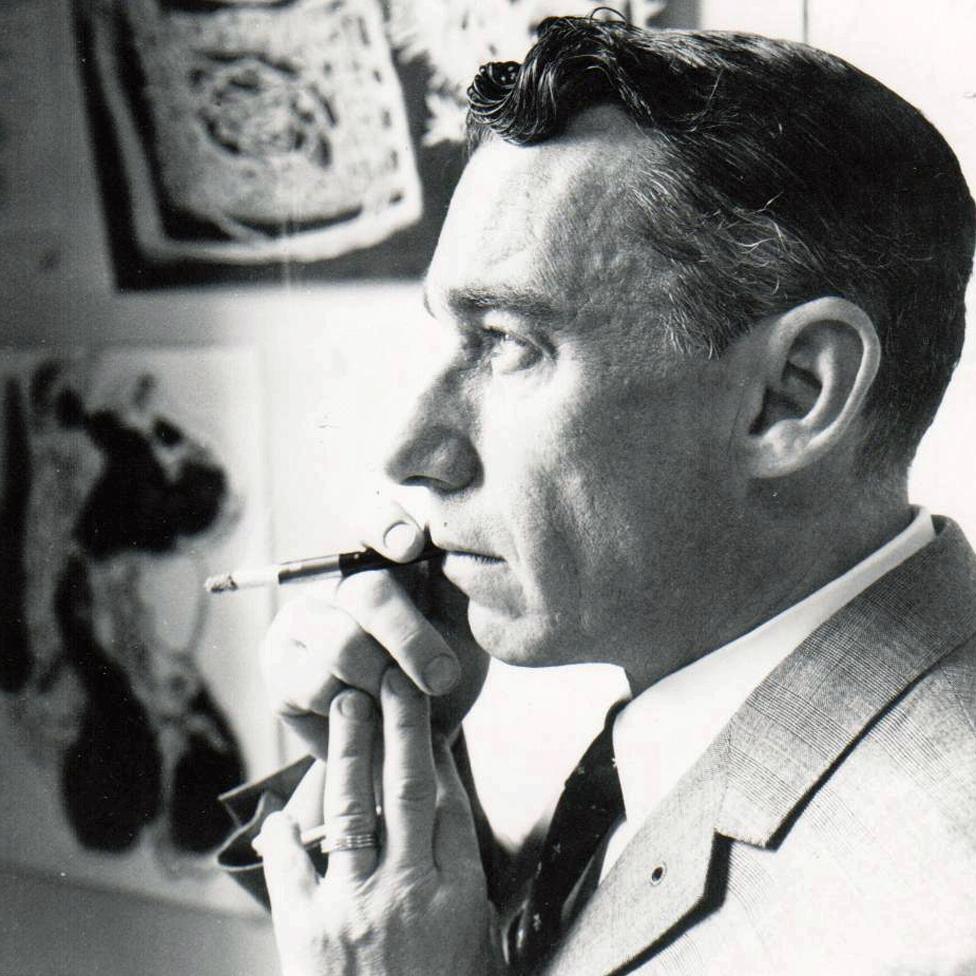

Arden, Glasgow, around 1967

One day Margo returned home from school in Miami Beach to discover that the "bad men" she'd heard veiled references to had caught up with her father. "Have you seen Dad?" one of her sisters asked. He'd been beaten up and his face was black and blue. But their parents never explained why he'd been attacked or by whom, or mentioned that the stranger sitting in the living room from then on was a bodyguard - and the children knew better than to ask.

While they always had a place to live and food to eat, and they always went to school, they lacked any love and care from their parents. It wasn't just the forgetting of their birthdays - the children were scared witless of their father. On his return from work he'd put them over his knee in turn and hit them with a table tennis bat in retribution for any wrongdoings, while their mother watched, looking vindictive.

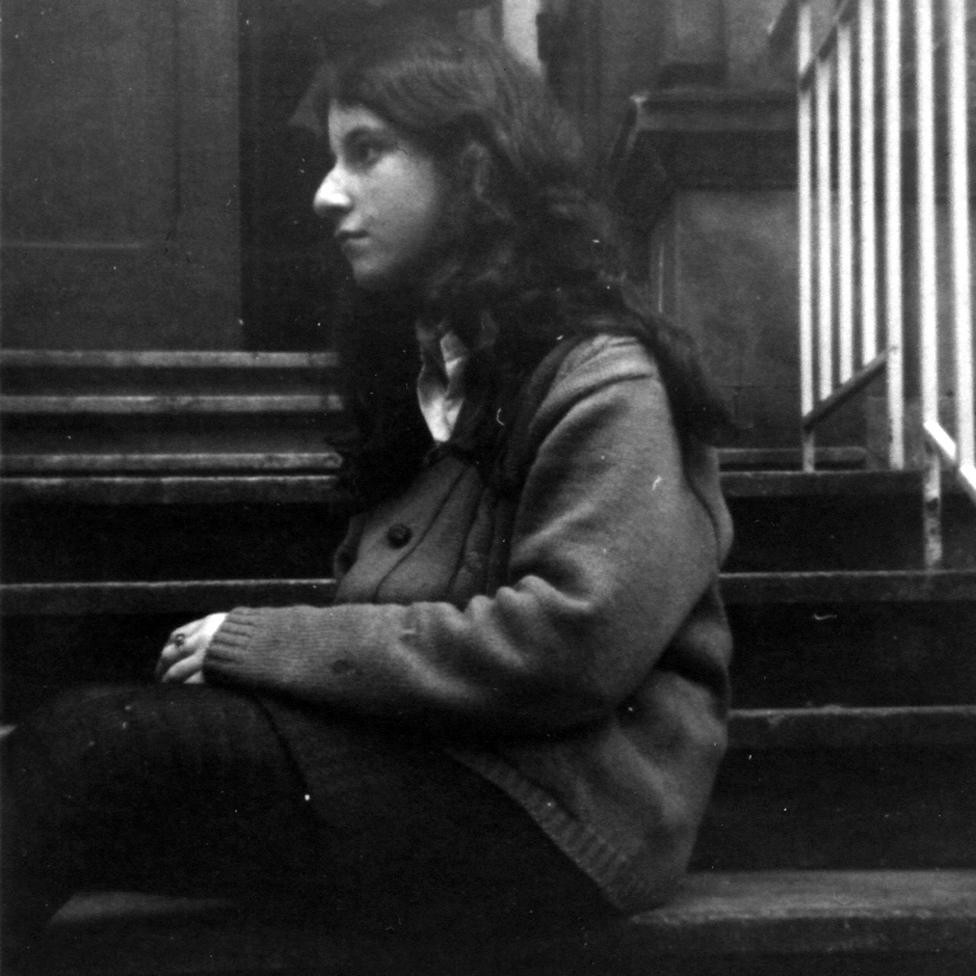

Margo on the front steps of her home in Hyndland, Glasgow, in 1967/8

Even though Margo was terrified of her father, she initially refused to have the nose job. It was only when her closest sister later came to her room, crying and wringing her hands with anxiety, that Margo realised she didn't really have any choice. "Please, please do the nose job," her sister implored. "If you don't do it, Dad won't let me leave home."

They were all desperate to escape from their parents, and Margo couldn't stand in her sister's way. "I had this feeling of going numb," she says. "All I wanted to do was protect my sister."

At the nose doctor's Harley Street office, Margo was shown a portfolio with page after page of different noses. Arden then left his daughter at the hospital where the operation would take place and flew back to Glasgow.

Three days later - her nose still in bandages, her eyes still black and swollen - 13-year-old Margo made her own way home to Scotland.

Find out more

Margo Perin spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service

It wasn't long before Arden announced that the family would be moving again. London, he told them, was a better location for expanding the business. When Margo's younger brother asked what kind of business, he replied: "Don't forget to bring your sweater."

Within a couple of months of arriving in the new city, Margo realised she was in deep trouble. "He's going to kill me," she sobbed down the telephone to her older sister, who'd managed to stay behind with her boyfriend in Glasgow.

"Who's going to kill you?" her father's voice boomed from behind her, as he ripped the phone from her hand, grabbed her by the hair and twisted her head to one side until she blurted it out.

On her last afternoon in Glasgow she'd slipped out to a pub, looking for a friend she'd wanted to say goodbye to. When she hadn't found him, she'd accepted a drink from a bearded stranger and they'd ended up back at his flat, where Margo watched curiously as he cooked up a mixture of brown powder and water on a spoon, drew the liquid up into a needle and poked it into the crook of his arm. They'd had sex on the cold black-and-white floor tiles in the bathroom, before Margo eased herself out from under his sleeping body to make it home before her regular bath time - her last in the Glasgow house.

Now she was pregnant and her father was calling her every name under the sun, punching her in the abdomen and demanding to know whose baby it was.

Margo didn't want to have the abortion, but as with the nose job, she had no choice. Her mother pushed her into a taxi, threw in an overnight bag and made a point of telling her how difficult it had been to arrange.

The law making abortions legal in England had been introduced two years earlier, in 1967, but disapproving attitudes often prevailed even so, especially when it came to unmarried under-age girls.

At the hospital in south London, Margo was put in a room of her own just off the labour ward and told not to speak to anyone. She could hear laughter, chatting and newborn babies crying. One of the nurses muttered "slag" under her breath, as she left the room.

Margo (left) on a family holiday after her nose job and abortion - her mother had made her cut her hair

After finally leaving home at 16, Margo began to self destruct - going from boyfriend to boyfriend, living in bedsits and squats, and using drugs.

But then, at 19, she was diagnosed with cancer - Hodgkin lymphoma - and was told she could easily die. "I knew I wanted to live," Margo says, "and I really wanted to make something of myself." When she had recovered, she started turning her life around.

By this stage she had very little contact with her parents, and the further away she got from them the better she felt.

Margo in San Francisco, 1986

But her strange upbringing continued to puzzle her.

It was only years later, when one of her sisters wrote a letter to the New York Times, and it was printed on the Letters to the Editor page, that Margo began to learn the truth about her parents.

The letter was noticed by her father's sister-in-law, part of the extended family Margo and her siblings had never known. The FBI was looking for Arden, the sister-in-law explained, and had interrogated them all.

More information came in 2007, when Margo's brother's wife managed to locate Arden's death certificate. He had died three years previously in Eastbourne, Sussex, after a series of strokes; his occupation was listed as "Economist, retired".

When Margo sent this to the FBI with a request for his records, they returned a 100-page file with details of a criminal career stretching back to the 1940s.

The extent of her father's deception hit her, she says, "like the sensation in your stomach when a lift suddenly hits the ground floor after floating in mid-air". Arden had been intertwined with the New York mafia and was wanted by the FBI for bankruptcy fraud to the tune of $140,000 - about $1m in today's money. He'd been an expert at persuading people to invest in things that didn't exist. In Scotland he'd sold shares in a whisky business, which operated out of a warehouse that didn't contain a single drop of whisky, never mind a barrel. He'd spent almost his entire life on the run, an international fugitive, with his family in tow.

Margo in Italy, 1998

Margo felt stained. "My father's profession was stealing money," she says. "He was a gangster who really liked getting the better of people, he was a low-life."

But why on Earth had he forced her to have a nose job?

Margo's theory is that he was concealing the fact that he was Jewish, and feared that her nose would give him away.

Growing up, Margo and her siblings hadn't known anything about their ethnicity. The subject of where the family came from was one of many their parents had always skirted around, though people always used to tell Margo that she "looked Jewish". Eventually Margo concluded that her father thought her nose might undermine the false identity he had constructed for himself.

"It makes me feel nauseous just thinking about it," she says. "It was so cruel what he did."

Is there a "Jewish nose"?

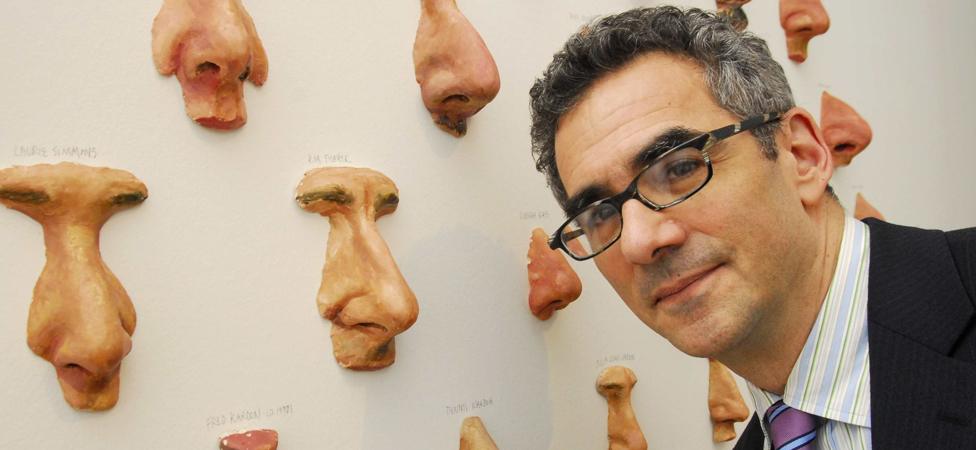

The artist Dennis Kardon with his installation, 49 Jewish Noses

In Tablet Magazine, earlier this year, historian and theorist of the body and face Sharrona Pearl declared that the Jewish nose was "not really a thing, external".

"There is no such thing as a Jewish nose. There are Jews, and they have noses, just like almost everyone else. Those noses are in no way remarkable or significantly different from the noses of the general population," she wrote. "The big (often hooked, frequently grotesque, generally repulsive, and highly caricatured) Jewish nose is a myth."

To support this conclusion, Pearl cited research by anthropologist Maurice Fishberg, who "measured 4,000 Jewish noses in New York (with calipers!)" in 1911.

She also noted that Jews only began to be depicted with large hooked noses in the 12th Century.

Pearl underlined that she had nothing against big noses, on whomever they may be found - "which is pretty much everyone, everywhere, in roughly equal proportion".

Now 64, Margo has many achievements to look back on. Although she left school without a single qualification, she went on to become a writer, and a teacher of creative writing in universities, colleges and schools, in both in the UK and the US.

Although she loves children, she never had any of her own. She gave herself intellectual reasons for opting out of parenthood, but now believes it may have been a consequence of the trauma of her forced abortion at the age of 14.

Margo at San Francisco County Jail, 2006

The idea that helping other people to express themselves through writing would bring her catharsis was never really on Margo's radar, but when she began teaching creative writing and poetry in prisons she found that she really identified with the incarcerated, powerless men and women she was working with - because that's how she'd felt as a child. Her parents had been her jailers.

"The violent men were letting me see the humanity inside them, and that was very comforting," she says. "I felt loved by them, and I never got that from my father." Not only was she helping the prisoners come to terms with their pasts through their writing, she was coming to terms with her own.

Helping others to overcome trauma has become the central point of her teaching. Personal stories of healing are also at the heart of her three published books.

Processing her childhood has taken Margo years - she's had decades of therapy - and it's a work in progress. But her father was a sociopath and she's not like him, nor "twisted" like her mother. As her therapist keeps telling her, she's nothing like the two people who brought her into this world.

"I have a very loving relationship, I'm not violent and I don't rip people off," says Margo, who returned to the US in 1986. "I should look back on my life and feel good about myself and everything I've achieved in spite of them."

Margo Perin is the author of an autobiographical novel, The Opposite of Hollywood

All images copyright Margo Perin unless otherwise stated.

You may also like:

Pauline Dakin's childhood in Canada in the 1970s was full of secrets, disruption and unpleasant surprises. She wasn't allowed to talk about her family life with anyone - and it wasn't until she was 23 that she was told why.

Read: 'The story of a weird world I was warned never to tell'