The woman who dares to run a feminist radio station in Afghanistan

- Published

The northern Afghan city of Kunduz is not the kind of place you'd expect to find a radio station run by women, promoting women's rights. But this is precisely what Radio Roshani is, and it's broadcasting today despite several attempts by the Taliban to kill its founder and editor, Sediqa Sherzai.

Radio Roshani broadcasts to a man's world. In most of Afghanistan, tradition has long dictated that women and girls are rarely seen or heard outside the home.

Amazingly, many men actually consider them their property.

In 2008, Sediqa set up Radio Roshani to challenge such attitudes but quickly found herself at loggerheads with the Taliban. Although no longer in government, it has remained a force to be reckoned with in many parts of the country. At first it warned Sediqa to stop broadcasting. Then, in 2009, rockets were fired at the station.

Briefly Sediqa halted broadcasts. She asked the Afghan government for protection, but it became clear that none was forthcoming. So after a few days she went back on air, "because we just couldn't give in to threats".

There has continued to be much local resistance. Men have often told Sediqa that she is leading local women astray, and promoting conflict between men and women in the home.

"These actions are so bad that you deserve to be killed - even more than an American does," they told her.

Find out more

Listen to Mike Thomson's radio report on Sediqa Sherzai and Radio Roshani on The World at One at 13:00 on BBC Radio 4 - or catch up online afterwards

It's part of a series on the importance of local radio in places that are isolated or plagued by conflict - listen to Mike's report on the two-wheeled station operating in South Sudan's largest camp for displaced people here (from 27 minutes 28 seconds)

So it was with particular horror that Sediqa watched Taliban sweep into Kunduz in September 2015, taking complete control of the city. Very soon her phone rang.

"Someone speaking in the Pashtu language asked me where I was, wanting me to give my exact location," says Sediqa, who mostly speaks Dari (an Afghan version of Persian). "I wasn't sure who this person was and was suspicious. After that I turned off my phone and did my best to get away."

This was a wise precaution. After finding the radio station's staff had fled, Taliban fighters destroyed the station's archives, stole its equipment and planted mines in the building.

Even though they were eventually driven out of the city, the station remained closed for two months while explosives experts defused the mines and staff replaced the missing equipment. But death threats against Sediqa and her team have continued ever since.

People of Kunduz returning home after the Taliban takeover in 2015

Radio Roshani promotes womens' rights largely via phone-in programmes. One of the commonest concerns among women in Kunduz, Sediqa Sherzai says, are disputes that sometimes arise between wives in polygamous marriages.

"A lot of men, as soon as they have some money, go for a second or third wife, and so on," Sediqa explains.

According to Islamic convention, this is acceptable in cases where the first wife cannot bear children, she says, but in practice it's mainly done "for sex life purposes".

The husband is supposed to promote justice and harmony among his wives at all times, but Sediqa says they often don't. Most disputes between wives arise because the husband shows favouritism to one over another, she says.

"When the second wife brings more children, she's being treated more favourably than the first. And if the first or second wife are illiterate and the man then gets an educated wife, again she is treated more favourably because she is more educated," Sediqa says.

Often the wives who have the hardest time are those who did not consent to the marriage, having either been sold to the man by their parents or given to him in lieu of a relative's debt.

She adds that it's very rare for the women to support one another, and to apply collective pressure on the husband to behave well.

"There is little understanding or sympathy between them, because of the tensions in the marriage. Some are jealous of other wives because they are closer to the husband, while they [themselves] are more distant. So there is often hardly any co-operation between them."

While Radio Roshani is now the only radio station in Kunduz run by a woman, there are three others that were launched by women, and which still broadcast some programmes for women even though they are now mainly run by men.

Zohal Noori, who works both for Radio Roshani and one of the other stations, says that some men tune in to women's programmes, and that this is helping to change attitudes.

More are now willing to allow their wives to go to work and become active in the local economy, she says.

A growing number are also permitting their wives and daughters to be examined in hospitals, Zohal says, thanks largely to an influx of women doctors. There are still men, though, who regard this as unacceptable.

"They take [their wives and daughters] to clerics, who just tell them to read specified parts of the Koran. These women have no option but to just put up with the situation. Some get very depressed and some have even taken their own lives," Zohal says.

But if in general the situation for women in Kunduz has been improving, there have also been setbacks, partly because of a shaky security situation - underlined by a new major Taliban incursion on 31 August, which led to battles across the city.

"There are lots of assassinations, kidnappings and crime," Zohal says. "Kidnappings are very common at night and things are just getting worse and worse."

As a result, some families that had begun to allow girls to go to school with their brothers are now changing their minds.

It's also feared that talks now being held between US and Taliban representatives, could end up unravelling the progress made on women's rights that Radio Roshani and the other women broadcasters have fought for for so long.

The worry is that in the haste to pull its forces out of Afghanistan, the US will let the Taliban bring back Sharia (Islamic law).

"We're hoping that the peace negotiations will become a real peace," Sediqa says. "And not at the cost of women sitting back at home all day, and that all our achievements are not reversed."

You may also be interested in:

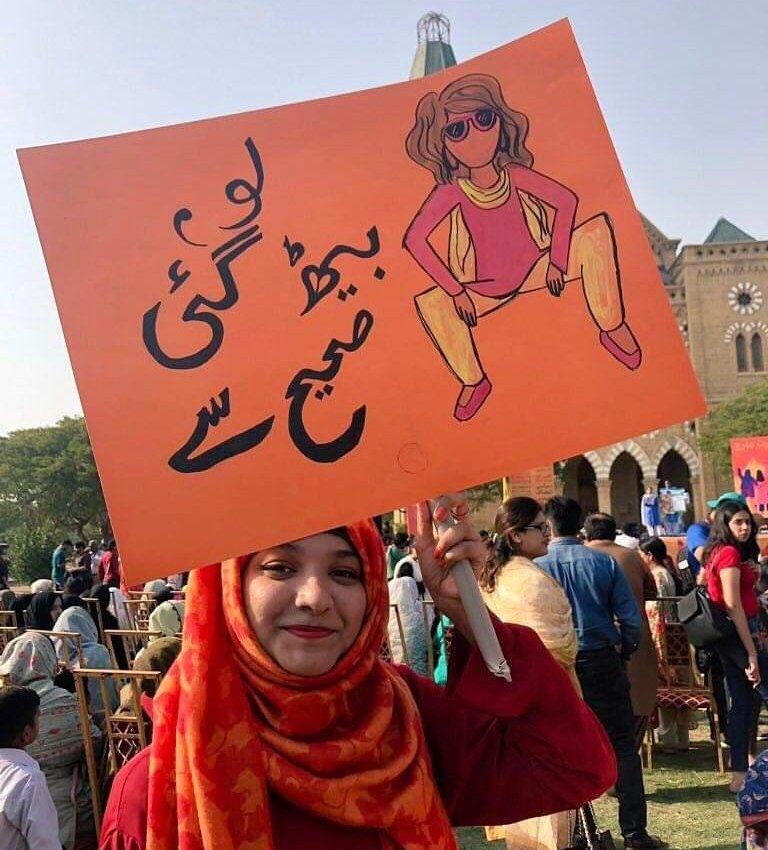

When Rumisa Lakhani and Rashida Shabbir Hussain created a placard for an International Women's Day march in Pakistan, they had no idea just how much it would place them at the centre of a fierce national debate.