Moneta Sleet: The great black photographer you've never heard of

- Published

It's 50 years since photographer Moneta Sleet became the first African American to win a Pulitzer prize for journalism. Has his work received the recognition it deserves?

On 9 April 1968, Moneta Sleet Jnr made his way to the front of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, as the funeral of Martin Luther King Jnr was about to begin. He found a position that allowed him to see Coretta Scott King, the civil rights leader's widow, and the photograph he took of her won him a Pulitzer Prize.

It almost didn't happen. Initially, no black photojournalists were selected to cover the funeral, but when word of this reached Mrs King, she insisted that the black media be represented. If Moneta Sleet were not allowed into the church, she is reported to have said, there would be no photographers at all.

The shot that won the following year's Pulitzer prize for feature photography shows Dr King's dignified, veiled widow clutching her youngest child's head to her lap, while the eyes of her daughter, five-year-old Bernice, gaze mournfully across the church.

The Getty Images website only credited the photograph to Moneta Sleet after this story was published

Although Gwendolyn Brooks had won a Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1950, Sleet was the first African-American man to win one, and the first African-American to win one for journalism.

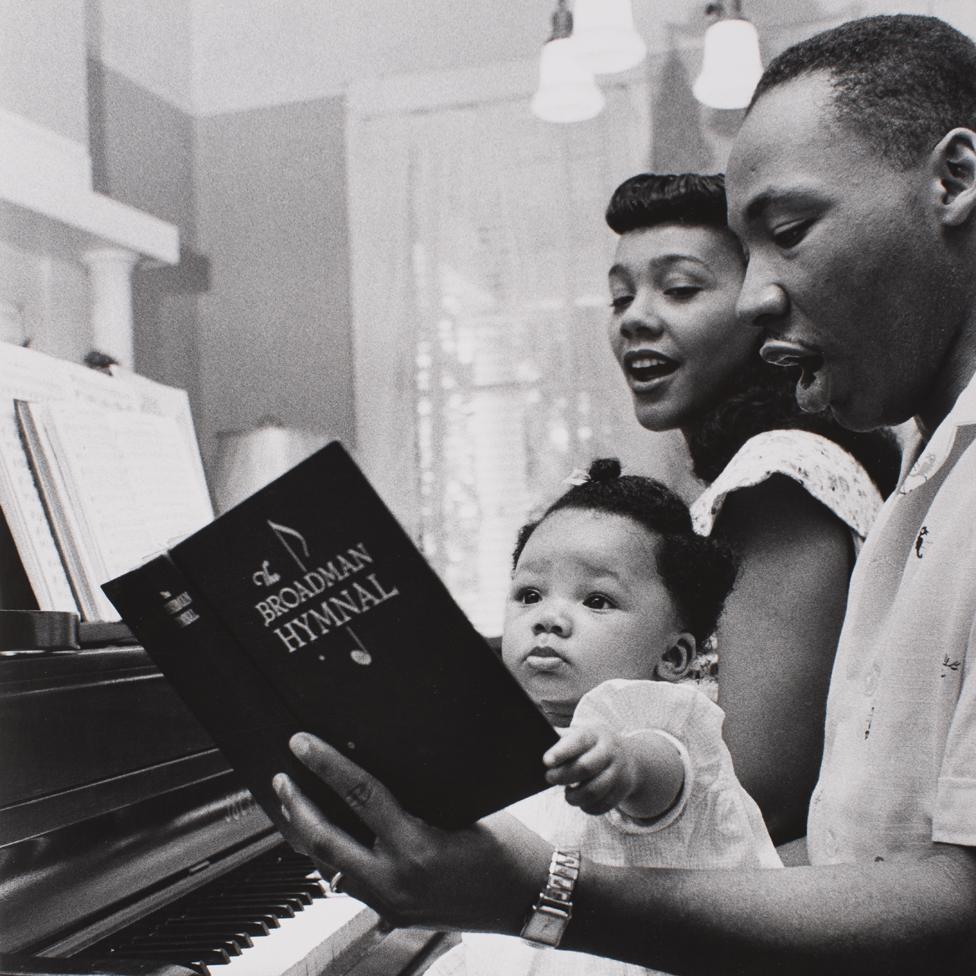

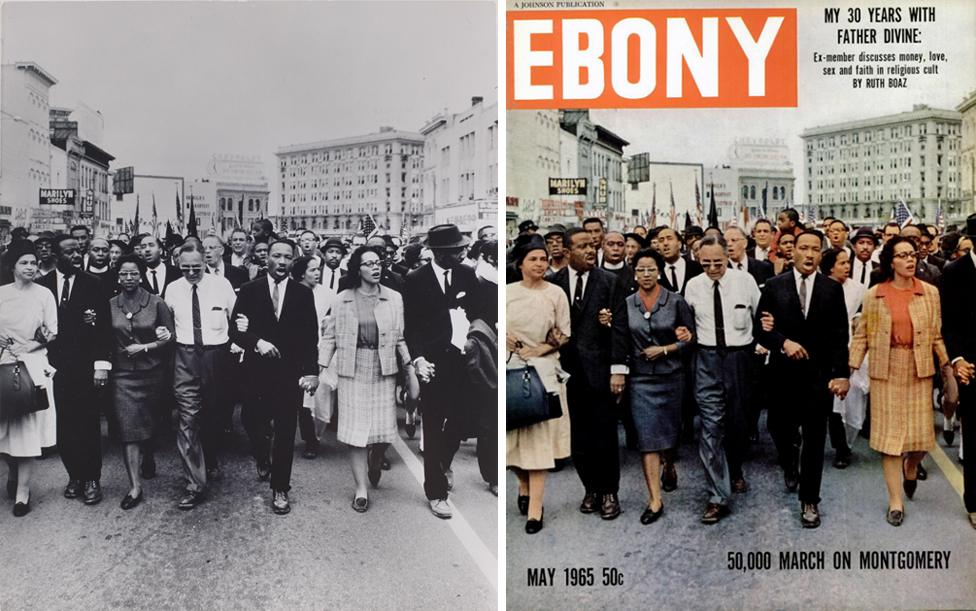

Sleet had come to know the Kings while covering the civil rights movement for Ebony, the leading magazine for the African-American market. In his first year there, he covered the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. He was on the ground for the 1963 march on Washington and the events in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

Sleet was in good shape physically, and tall, about 6ft 2in (1.88m), with a long stride. He would walk up and down the marches capturing the now iconic images - he estimated he had actually walked 100 miles on the 50-mile march from Selma to Montgomery. He would also often find himself in the way of police batons, fire hoses and dogs.

"Dad had many opportunities, thankfully, to cover seminal events in the life of the [King] family, in the life of Dr King. We all benefit from that history," says Sleet's eldest son, Gregory.

Sleet also accompanied Martin Luther King on his trip to Oslo to collect the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, which led to a memorable encounter for Gregory in an airport VIP lounge.

"My dad said, 'Stay right here,' and a few minutes later the crowd parted - it was sort of like the Red Sea - and coming through the crowd, walking, was my dad and Dr King. And Dr King walked straight up to me and extended his hand and I was in shock," Gregory remembers.

Gregory Sleet, Moneta Sleet and Martin Luther King in 1964

Many years later Gregory received an envelope from his father, containing a 8in x 10in black-and-white photo of the handshake. Accompanying it was a programme from the Nobel ceremony with a handwritten inscription: "To Gregory, for whom I wish a great future and whose father I admire very much [the word very is underlined], signed Martin Luther King."

Gregory went on to become the first African-American district judge in Delaware. The photo took pride of place in his office, hanging above his desk until his recent retirement.

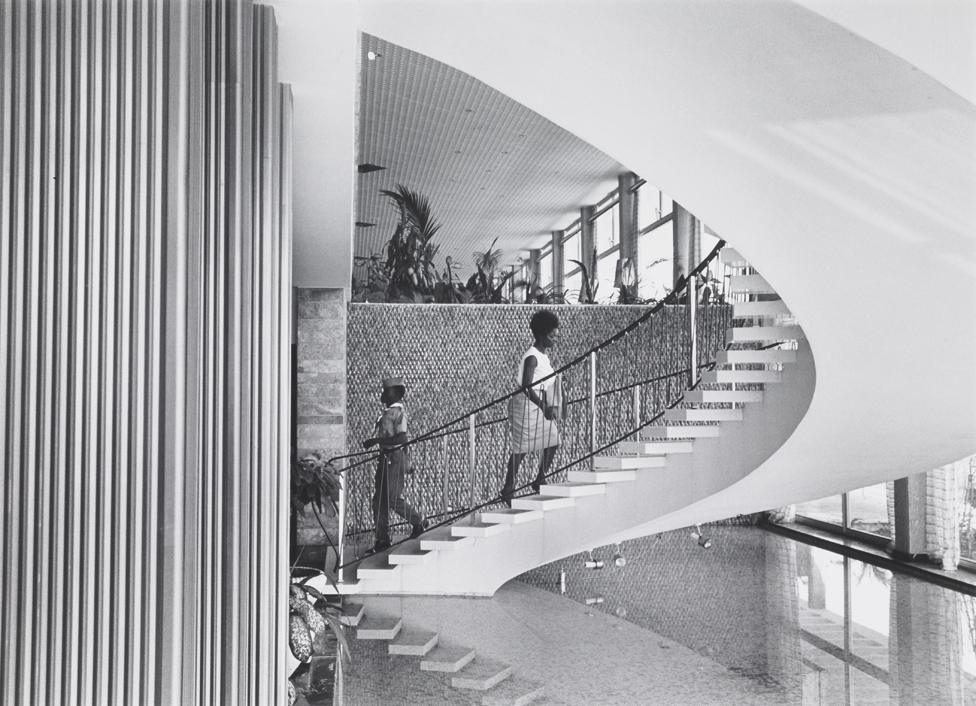

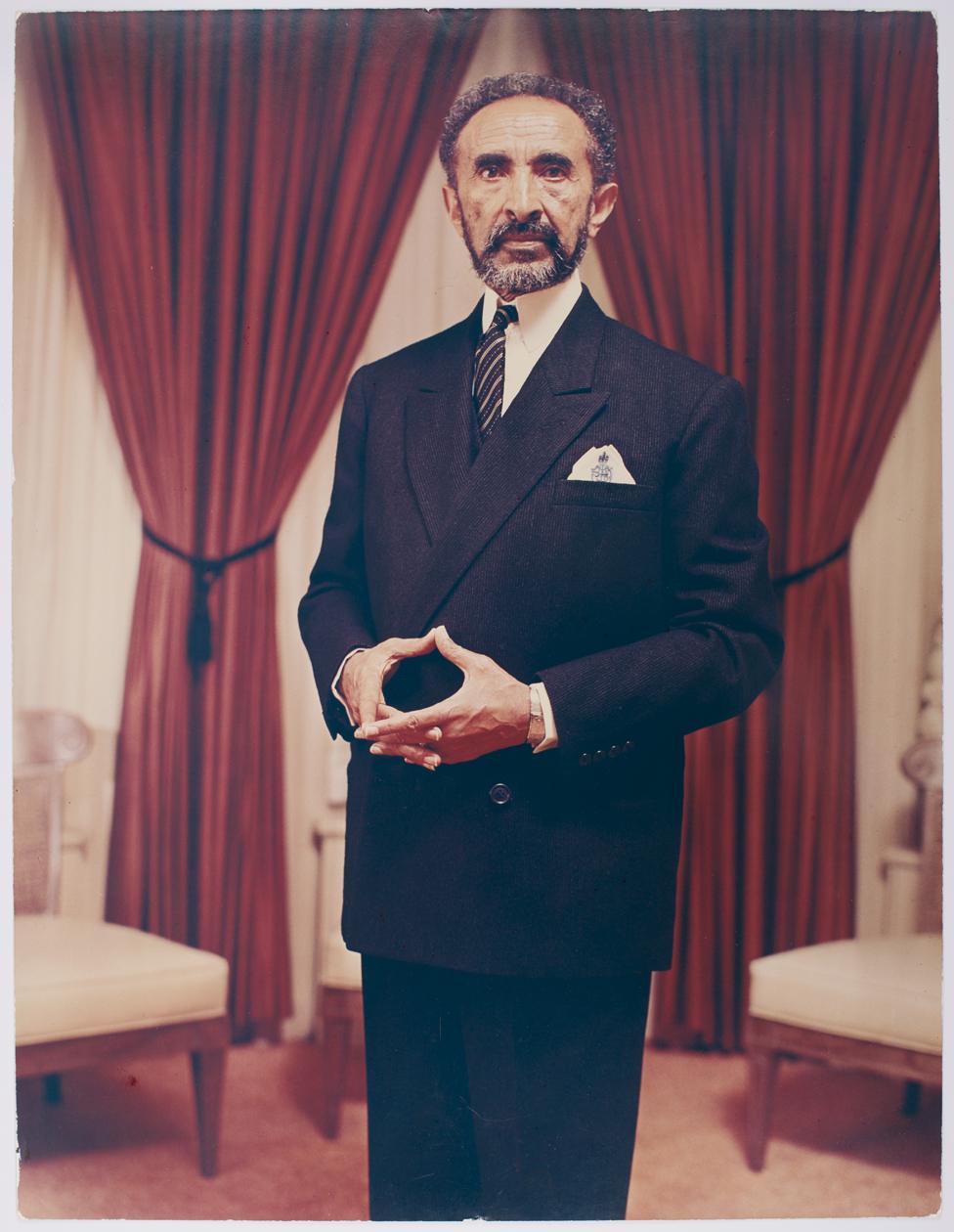

While Moneta Sleet may be remembered now mostly for his images of the civil rights movement, in his 41 years at Ebony magazine he photographed almost every aspect of the black experience in the US. His early assignments for the Johnson Publishing Company, which owned Ebony, included photographing prison inmates on death row, a hospital in Harlem, and a beauty contest. He shot nearly every black celebrity from the 1960s to the early 1990s and travelled widely in Africa, photographing the countries newly freed from colonial rule.

A stairway in Monrovia, Liberia, 1964

Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia

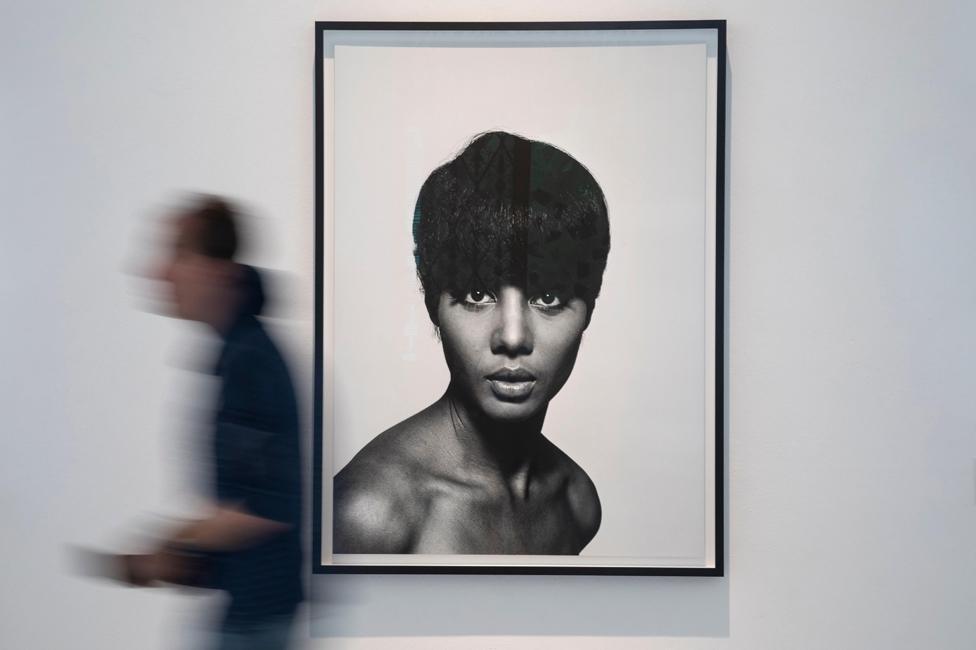

An exhibition titled the Black Image Corporation, curated by the installation artist Theaster Gates, recently showcased Sleet's fashion photography, alongside that of fellow Ebony photographer Isaac Sutton.

Gates selected these images from the photographic archives of Ebony and a sister publication, Jet, which were bought earlier this year by the Getty Institute and the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). In the long term, this may make Sleet's work more accessible to the public, though the NMAAHC says it has "much work to do to catalogue, preserve, digitise, and store the archive, and to develop a plan for long-term dissemination".

Black Image Corporation: fashion shots by Moneta Sleet...

... Isaac Sutton (left) and Moneta Sleet (right)

Russell Frederick, vice-president of Kamoinge Inc, an African and African-American photography collective founded in 1963, says Sleet has been slowly forgotten in the 23 years since his death.

"As a matter of fact, what he has accomplished has been under-represented and ignored," he told the BBC. "The reason is flagrantly obvious. Mr Sleet worked for a black publisher, whose primary objective was to cover the achievements and concerns of black America."

Prison cell block, Jackson, Michigan, 1953

Frederick says that when he asks young photographers, African-American or white, to name a great black photojournalist or portrait photographer Sleet's name "is never mentioned".

"Very few are aware of the extraordinary significance of Ebony and Jet magazines. Moneta's contribution to American history is unknown to far too many. There should be a scholarship in his name."

Find out more

Being a black journalist in 20th Century America made it impossible to remain an impartial observer. Sleet was born in Kentucky in 1926, in the era of segregation, and served in a segregated unit in the US Army in World War Two. On his return, after finishing his degree at Kentucky State University, he travelled north in search of opportunities that were denied to African Americans in his home state He received his master's degree in journalism from New York University in 1950.

Sammy Davis Jr in 1956

Miles Davis in 1961

Gregory Sleet remembers going to visit his grandparents in the south.

"There would be coloured facilities and white facilities that we'd have to stop in along the way, and you bet your bottom dollar he didn't like it. He was a civil rights activist. It's one of the things that drove him and I think motivated his expression through his camera," he says.

"My dad felt that there was a story that he was telling, but that he wanted to tell the story from his perspective as a black man in America. He said that he had a point of view and he wanted to represent that point of view with his camera lens. I think that informed a lot of his photography and a lot of his journalism and a lot of his art throughout his career."

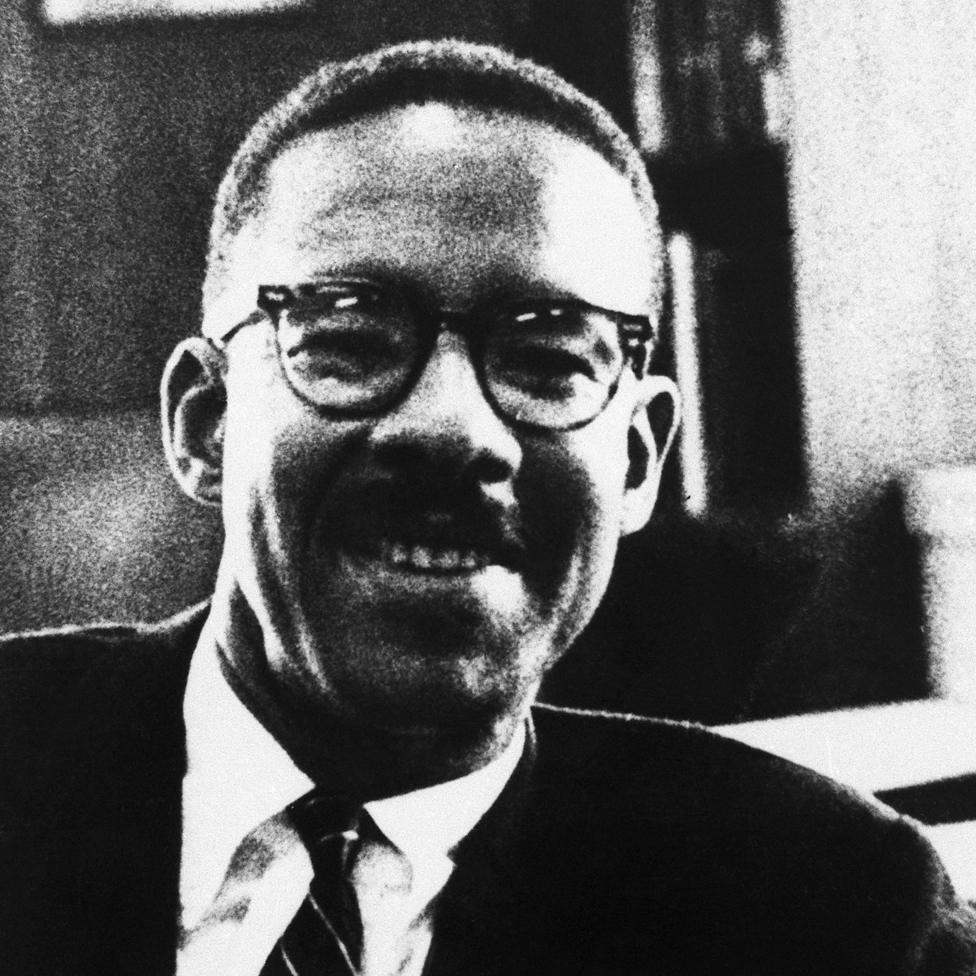

Moneta Sleet 1926-1996

This was certainly true when he shot the Pulitzer-prize-winning photograph at the funeral of Martin Luther King.

"I was photographing the child as she was fidgeting on her mama's lap. Professionally, I was doing what I had been trained to do, and I was glad of that because I was very involved emotionally. If I hadn't been there working, I would have been off crying like everybody else," he said later.

Black Pulitzer-winning journalists

A 2016 study in the Columbia Journalism Review found that 84% of 943 named winners had been white, while only 30 had been African-American, external

Four more African Americans have been named as winners since then

Since Moneta Sleet (1969), four other African Americans have won the Pulitzer prize for feature photography - Matthew Lewis (1975), John H White (1982), Michael duCille (1988) and Clarence Williams (1998)

Gregory Sleet also remembers this moment.

"We all a felt a great sense of loss. My dad felt it more acutely then I ever could have," he says. "He described to me how emotional it was for him. I know at various times he was on the verge of tears. He was a seasoned journalist but he was a human being and he admired Dr King very much."

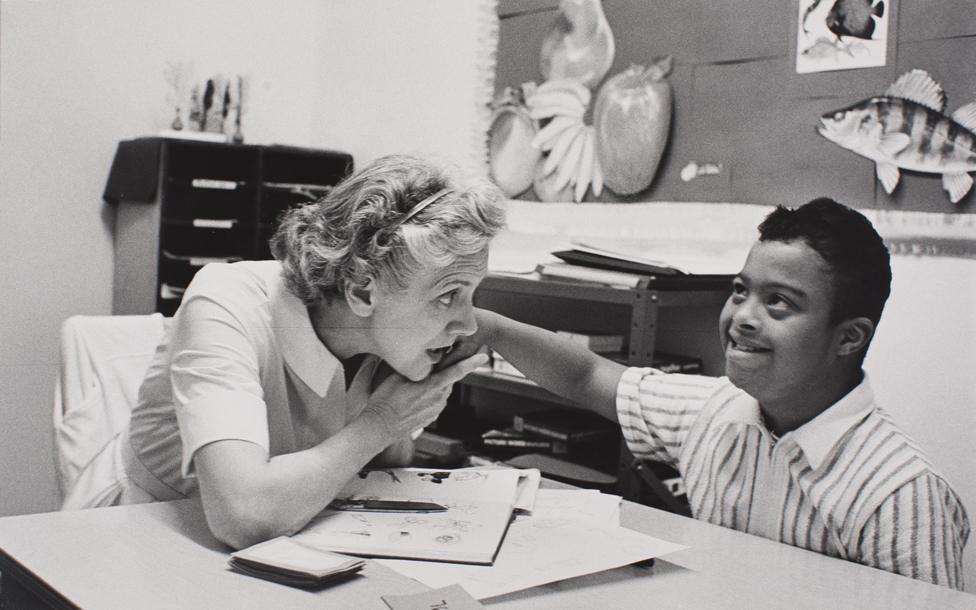

The haunting look in Bernice King's eyes captured the pain of the moment, but Gregory Sleet says that children were generally one of his father's favourite subjects, providing a break from the ugliness he often had to chronicle.

One of the assignments he enjoyed most came quite early in his career, when he went to photograph a special needs school attended by his second son, Michael, who had Down syndrome.

Which of his own photographs was Sleet's favourite?

Gregory says it was a photograph taken on one of the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, an image of a woman with a rain hat on, and her head turned to the sky.

"You could see it was raining hard, you could see that in the black-and-white photo, and she's clapping and she's belting out a song, she's marching for civil rights," he says

Despite many offers of work elsewhere, Moneta Sleet remained at Ebony magazine throughout his career. He died of cancer in 1996 at the age of 70, shortly after returning from covering the Olympics in Atlanta.

The report of his death in the New York Times, external spoke of his "gentle engaging personality... his perpetual optimism, his ever-present smile and his knack for making others smile even when they didn't feel like it".

All photographs courtesy of Saint Louis Art Museum unless otherwise specified: Moneta Sleet Jr, 1926-1996, either chromogenic print or gelatin silver print, either Gift of Johnson Publishing Company or Gift of Moneta Sleet Jr. © Estate of Moneta Sleet Jr.

You may also be interested in:

'I choreographed This is America, and this is my story'