'How I became a secret daytime DJ'

- Published

In the 1980s, many British South Asian teenagers were expected to spend evenings at home, so an underground club scene began to emerge in the afternoons. One of the people behind the "daytimer" trend in Bradford, a young DJ called Moey Hassan, told the BBC's Kavita Puri how it began.

It is December, 1985 approaching ten at night. Moey Hassan is driving his taxi in Bradford when he stops to pick up a young man. It's a DJ who wants to go to a nightclub in Leeds. The fare is £5, but - to Moey's annoyance - the passenger has no cash. He says he'll pay him later. In the meantime he gives him a cassette, a tape that will change Moey's life.

Moey had been born in 1966 in Mirpur in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. He has few memories from living there but recalls the house they lived in was made of simple materials and there was lots of family around - his great-grandfather, his grandmother and many others. He laughs heartily as he remembers always being thrown from one auntie to another.

He came to Bradford when he was four. The family lived in a small house not far from one of the city's many textile mills, where his dad worked shifts. Moey called everyone in the street "uncle" and "auntie" and he thinks they really were, in some way, related to his father.

His mum was a housewife. His parents spoke little English - they spoke Mirpuri at home - so Moey was their translator. It was a strict household. Even when he was 18 he wasn't allowed out after nine. "And if I did go out, I would sneak out through the bathroom window and then climb in back up the drainpipe... It was dangerous because there were spikes and everything." He breaks into his infectious laugh again. He tells me he would be visiting friends or going out clubbing.

One day his brother suggested he take his grey Datsun taxi out at night. Moey jumped at the chance. Soon he was earning good money and enjoying his freedom.

On that December night when he begrudgingly accepted a tape in payment, he played it on the way home. "I was used to the Top 40 Charts, and I thought that was all there was in the world." What he heard were sounds he'd never experienced before. The Chicago House scene had just come in with artists like Daryl Pandy and Mr Fingers. There was underground R'n'B, and soul music. "I was just taken aback, I was blown away," Moey says.

Find out more

Moey Hassan features in the new series of Three Pounds in My Pocket, which starts on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 on Friday 6 December

The man who gave him the tape was a well-known local DJ. Moey picked him up again in his cab, and this time he asked for a cassette. The DJ soon became a regular customer, and Moey wasn't interested in cash, he wanted payment in tapes and DJ-ing lessons. Soon he was spending afternoons at the DJ's studio, where the walls were covered in his awards and newspaper clippings. There, Moey learnt about music and mixing. Then he started to get gigs in clubs. It wasn't long before Moey was "DJ Moey", and he was thriving.

Moey Hassan learning the DJ's art from Mark Lacey in 1986

"When I look at myself as an Asian man in the UK, it's very difficult to have a sense of belonging. And in that environment it was great," he says. His success as a DJ could be measured in the takings on the bar. "All of a sudden you had a sense of belonging and you were earning your money deservedly."

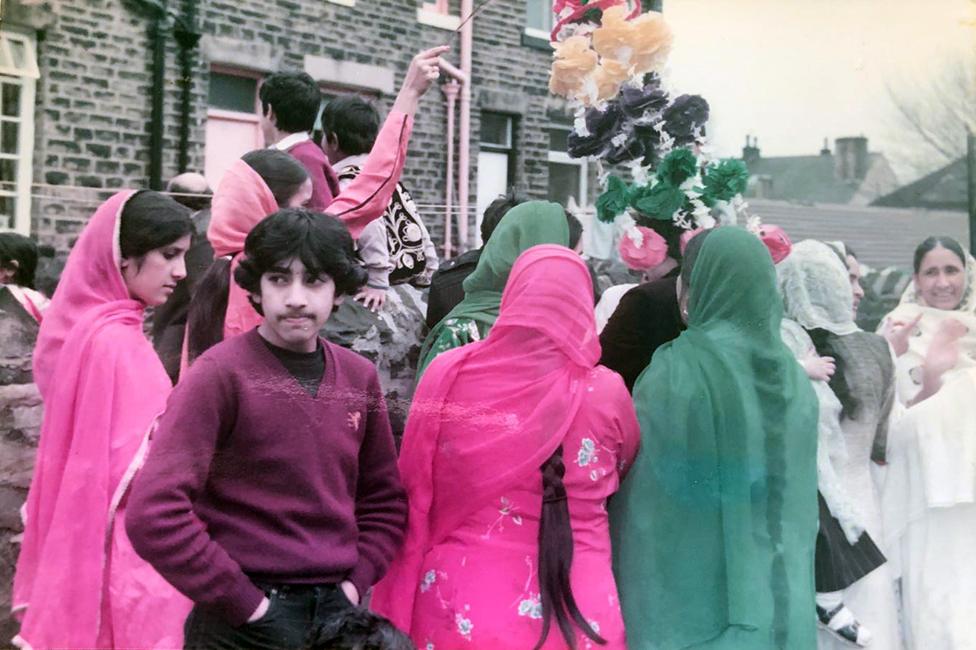

Moey's dad was one of thousands of men who had come from Mirpur to work in the textile mills of northern British cities, beginning in the early 1960s. By the 1980s their wives had come over too, and their children, many born here, were coming of age. There were now more than one million South Asians in Britain, not just Mirpuris, but also people from other areas on the Indian subcontinent like the Punjab or Sylhet in Bangladesh - others were Asians from East Africa.

Many of the second generation had lived through the outright racism of the 1970s, epitomised by the National Front, and they were finding ways to express their identity not just in music, but film and theatre too. Like Moey, they were forging their own path, in a very different way from their parents.

The clubs Moey DJ'd in were almost never frequented by young British South Asians. Moey knew that a lot of South Asian kids, like him, weren't allowed out at night, "and especially Asian women". There was new music on the scene now - bhangra. It mixed Punjabi folk songs with Western music. He'd heard people playing it at college. He once went to Tumblers, a club, during the day - and they were playing bhangra to a handful of British South Asian kids. It gave Moey a business idea.

He got together with some other Asian DJs and hired the Queen's Hall, which was next to a further education college, where they put on a club session from midday to four. It was held every Wednesday, as that was a half day at the college. It took time to get off the ground, but with targeted promotion and word-of-mouth, soon around 300 young British South Asians were turning up to this new underground club scene. The events became known as "daytimers".

DJ Radical Sista played at many of the Bradford daytimers

Moey recalls how South Asian girls turned up in their salwar kameez with a carrier bag. They'd go into the toilets and emerge wearing jeans and a leather jacket. "They came out looking like Olivia Newton John," he says. They played bhangra, as well as bands like Loose Ends, Maxi Priest, and tracks from the Chicago House scene. "It was groundbreaking."

As Moey saw it, it was an opportunity for young British South Asians to express themselves on the dancefloor and let their hair down. "They needed an outlet. And that outlet was not available to Asian people at that time," he says. For Moey, it was good business too. Every clubber paid a £2 entry fee - not a small amount back then.

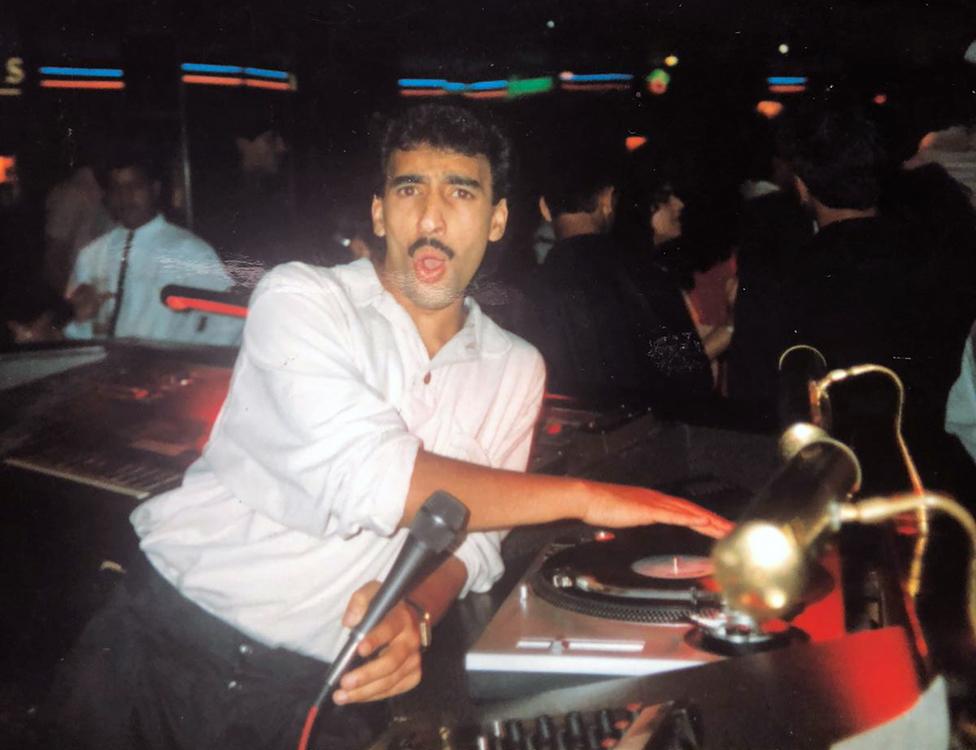

Moey Hassan at the microphone, after shaving off his hair and moustache

As he was on his decks he would look down at the dancers and feel elated. "To be able to move people was such a thrill. They felt free. They came from stifling homes, here they could express themselves. It was beautiful."

There was no alcohol. Even if they had wanted a licence, they wouldn't have been able to get one at that time of day. People who came were, like Moey, second-generation Mirpuris, or from Bradford's Punjabi community. "Back then religion wasn't really a problem" he recalls. Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus danced together in the Queen's Hall, Bradford, in the middle of the day. They formed friendships, even relationships - though they were discreet. But Moey points out that in some cases the women who came had no brothers to object to them being seen at this underground club. (Or if they did, they made sure their brothers weren't around.)

Later it became easier for young Asians go go out at night

After a year or so, Moey had bigger plans. He organised day-time events in larger venues in Bradford, like the Maestro. "I wanted them to experience a real nightclub with the lights and everything," he says. At the same time, daytimers were occurring elsewhere in places with large British South Asian populations - West London, Birmingham, Luton and in the Midlands - sometimes with well over 1,000 in attendance. Moey organised coaches to take young people from Bradford to some of them, though he always tried to make sure they were back in time for dinner at their parents' home. Moey even organised daytimers outside Bradford himself. It was at one of them in 1990, at Applejacks in Manchester, where he was approached to present a music programme called Bhangra Beat for mainstream British TV.

Moey says after a few years people eventually grew out of daytimers. He wanted to move on too. He was more interested in getting into mainstream music, and trying his hand at acting. Looking back, he is still amused his parents had no clue about this other life. "I know it's a bit bad," he says, "but we lied about what we were doing."

You may also be interested in:

When a family arrives in a new country, often the children are first to pick up the new language - and inevitably, they become the family translators. Researcher Dr Humera Iqbal describes what it's like to be a child responsible for dealing with doctors and landlords, bank staff or restaurant suppliers.