Pramila Le Hunte: 'I tried to be the first female British Asian Tory MP'

- Published

Of the 365 Conservative MPs elected last week 14 were of South Asian heritage and four of them were women. It's a far cry from 1983, when Pramila Le Hunte became the first British South Asian woman to stand for parliament as a Tory, writes the BBC's Kavita Puri.

In the late spring of 1983, Cambridge University student Bem Le Hunte was on her way to watch an address by Margaret Thatcher. She was with a group of friends, carrying a basketful of eggs. That's when the news reached her. It was about her mother - she had just been selected as the first British Asian female Conservative Parliamentary candidate in the forthcoming election.

The announcement caused huge media excitement. Bem, however, was unimpressed, although it did make her think she'd better not pelt the prime minister with eggs, as she'd been intending. Pramila recalls that Bem felt "terribly ashamed to be my daughter".

Unlike Pramila, nearly all British South Asians in the early 1980s voted Labour. Pramila says it was in their genes when they arrived in the UK.

"Because who gave them independence? Clement Attlee [the Labour prime minister]. Who was against us? Winston Churchill… So Labour was deified from day one.

"The good people of Britain were Labour. And the baddies were the burra sahibs, the important white gentlemen."

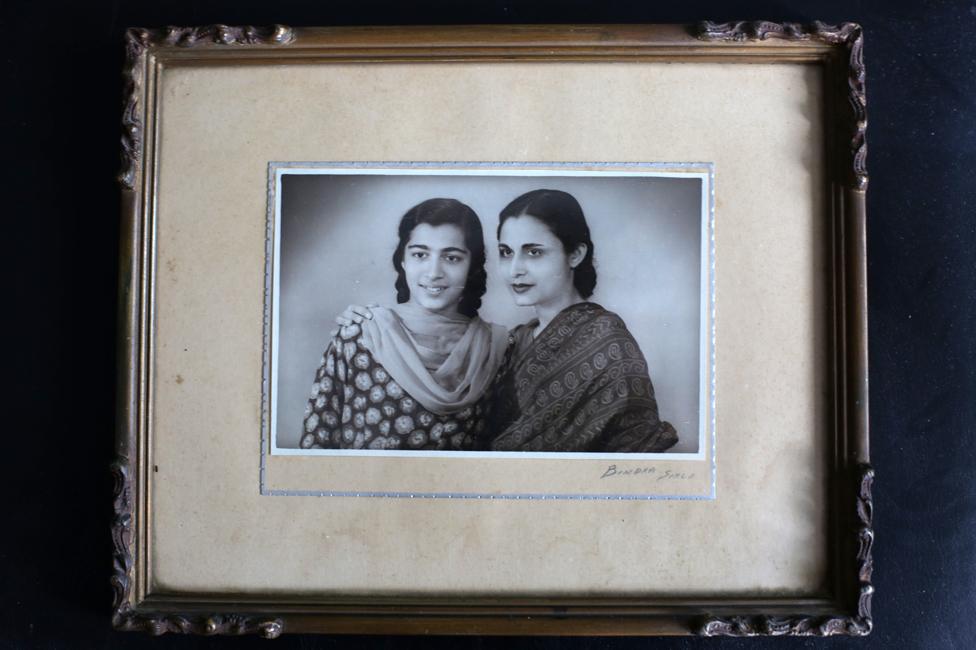

Pramila Le Hunte and her mother

When thousands came to post-war Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, many working the most difficult shifts in mills, factories and foundries, these early settlers also felt that the Labour Party "stood for the working man" like themselves, Pramila says.

She had lived a charmed life. Born in 1938, she had spent her early years in British India in "the jungle" in Mosaboni in Bihar. Her father supplied timber to the British copper mine there. They were the only Indian family living among "Britishers", as they were known then. She recalls hearing Mahatma Gandhi speak publicly about taking a stand against the British, during the Quit India movement. She decided, as a little girl, to try that out one late afternoon, at the company tennis courts where she used to meet her English friends. She picked up a stone and, throwing it, said, "All right, Margaret, quit India." She hit her target. Margaret responded by throwing a stone at Pramila, striking her on the head. It was to be Pramila's first political foray.

Pramila's first language was English. She still remembers the first poem she learnt:

A beetle got stuck in some jam,

he cried "Oh how unhappy I am!"

His ma said, "Don't talk, if you really can't walk,

you better go home in a tram."

She was an avid reader throughout her childhood, and in 1957 she went to Cambridge University to study English literature. There were few Indians around in those days and she liked to ride her bicycle wearing a sari. "I felt rather special. Must be a little bit of showmanship. I quite liked the idea of bombing around in a sari in King's Parade." She was delighted to be in the UK, free of all parental controls.

Find out more

Listen to Pramila Le Hunte in the new series of Three Pounds in My Pocket

The final episode can be heard at 11:00 on BBC Radio 4, on Friday 20 December

She admits she was not a typical Indian girl. She says there used to be a Poppy Day with celebrations and street parties, and she took charge of her college float, basing it on the Paris cabaret club, the Moulin Rouge. She got people to chant: "A shilling a kiss, a bob for two." Men would jump on the lorry and get a kiss, she says, shaking her head and smiling. "Now which Indian girl would do that?"

She met her English husband in her third year. They lived in India together for a number of years with their four children, before settling in Richmond, south-west London. There weren't many South Asians there then, she remembers, and it was the time of the Conservative MP Enoch Powell's Rivers of Blood speech, in which he criticised mass migration, especially from the Commonwealth countries. Her children suffered a lot from racism at that time, she acknowledges.

Pramila went on to study further to become an English teacher. It was important to her to be "top notch". She felt that "for an Indian wanting to teach English to the English… you have to have credibility." She went on to be a teacher at some of the most prestigious London day schools. She also supported the Conservative Party, becoming chairman of a Richmond Council ward. She was asked if she would consider putting her name forward for a number of seats with large British South Asian populations, and in 1983 she got selected to stand in Birmingham Ladywood, a staunch Labour constituency.

Pramila Le Hunte in the classroom

Even though Margaret Thatcher was known for anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric, she also saw potential voters among the million-plus British South Asians of the time.

She praised the community for its family values, hard work and entrepreneurial spirit. Local and national press were fascinated by Pramila. "I think it was an oddball interest… they asked me, 'Is this tokenism?' I remember saying, 'What's wrong with it?' Someone has to start somewhere."

Ladywood had a large British South Asian population - mostly Sikhs, and Mirpuris from Pakistan-administered Kashmir. When she met with them she would wear salwar kameez - baggy trousers with a long shirt - and she would cover her hair with a veil, so she could "mix and merge". Pramila's parents were Hindu Punjabis, and she felt there was a natural connection with the Sikh community, the majority of whom were Punjabi too.

"I dressed like them. It's the same ethic, ate the same food. We were no different."

Pramila Le Hunte in clothes she'd wear among the South Asian community...

Even though they were all Labour supporters, they told her they would vote for her. She rationalises it by saying, "I'm Punjabi. Their culture. Their person." They told her no politician had ever come to speak to them before. She would eat lunch sitting on the ground in their Sikh temples. Some of the community offered to protect her as she went around canvassing. She refused.

While campaigning, Pramila also met members of the Mirpuri community, whom she had never met before either on the Indian subcontinent or England. "Never met a single one until I went there. I was not moving in those circles." Yet she says they also perceived her as one of them. "I look the same."

Her father was from northern India, growing up near the borders of the North-West Frontier and she says she could almost speak their dialect. Even though she was Hindu and they were Muslim, the affinity was instantaneous, she says. "It was like striking a match." She mostly spent time with the women. They knew what she ate, she would speak to them about clothes, jewellery, arranged marriages, "girly stuff". And as their lives were quite restricted, they had many questions for her. "They were curious about the world outside and India."

... and in an outfit she would wear with white voters

The outfits changed when Pramila was canvassing in the leafier suburbs. She laughs as she says the English middle class would not take well to a woman in Asian clothing. "I never wore that. Never. I dressed in what would make them comfortable." She says she swapped the salwar kameez for trousers, a top and a scarf, while she was sipping sherry with the women of Ladywood in their twin sets and pearls.

There was hostility towards Pramila. One day, close to the election, she was going around with a loudspeaker on the back of an open-roofed lorry when a stone came flying towards her. "It happened so fast," she makes a whooshing sound. "It touched my hair. A bit of breeze came with the stone." She doesn't know who it was - or the motivation.

"So in my life I've had two stones hurled at me. One in Birmingham, and one as a little one being political. Two political stones."

Female British South Asian MPs

While the first male British South Asian MPs were elected in the 19th Century, there were no female equivalents until 2010

That year, six were elected at once - five from the Labour Party, and Conservative Priti Patel representing Witham, Essex

One of the Labour MPs was Shabana Mahmood - who won in Birmingham Ladywood, 27 years after Pramila Le Hunte's failed attempt

Patel (above) became a junior minister in 2014 and entered the cabinet in 2015 as Minister of State for Employment

Pramila admits it was tough canvassing in a Labour stronghold. She remembers that it was a time of huge unemployment. She recalls going to homes in the tower blocks around the Bullring area. People were at home she says because they didn't have jobs. "And you got abuse because Thatcher wasn't flavour of the day." There were even death threats. She admits she also got abuse for being non-white, though she doesn't like to dwell on it.

Pramila was at the count on election night. Clare Short - who would go on to be a Cabinet Minister years later - won for Labour. Pramila did, however, nearly double the Conservative vote in Ladywood. She says she knew she was never going to win such a Labour stronghold, but "I thought I would make an impression."

Pramila Le Hunte in 2019

She didn't stand in 1987. She and her husband had divorced by then and she knew the only seats available to her were ones with a South Asian population. These voters would not be able to accept an unmarried woman as an MP - so she felt it unlikely she would be selected.

Pramila went back to teaching. She is a published playwright, and is writing a book about her life. She is still a member of the Conservative Party, but thinks it must have forgotten her part in history. In the 2015 general election she approached her local Conservative office offering to help out behind the scenes, as knocking on doors is difficult for her now. They declined. She says she sent an email to the current Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sajid Javid, when he was standing to be the leader of the Conservative party, to help him with delivering speeches, but "not a dickie bird".

Now aged 81, looking back she acknowledges that by standing in the 1983 election she was "making footsteps in the sand for the next generation".

"More than that, somebody has to trailblaze," she says. "And I had the kind of mentality to do that. And the lack of fear. I was quite gutsy."

You may also be interested in:

It was unusual for first-generation Asian women to learn to drive after arriving in England in the 1960s and 70s, but some were determined to ignore convention.