'Abuse on the campaign trail doesn't shock me any more'

- Published

Racist slurs, rape threats, being chased with a sledgehammer - abuse of political candidates and their teams is on the rise. How do those running to be an MP cope in this toxic environment?

"I've been told that I'm not English enough, that I should go back to where I came from. I've been told that, because of the way my surname sounds, I'm a nobody."

Before she put her name forward as the Liberal Democrat candidate in Camberwell and Peckham, south London, 33-year-old Julia Ogiehor had a difficult decision to make. Was standing up for what she believed in worth the toll on her mental health?

And sure enough, she says, she faced a torrent of abuse, some of it racist. She was told that she didn't deserve to represent the seat, and should go and work in McDonald's.

"I'm human too, I've got feelings. I don't always have to be the strong black woman," she says.

Julia Ogiehor campaigning in south London

"I have cried on this campaign. I've had moments when I just couldn't get out of bed. I just didn't want to speak to anybody.

"I was prepared for the abuse on the right but I was dismayed, disappointed, hurt and then frightened by the abuse from Labour supporters."

For candidates running for election across the UK, the general election wasn't just a succession of 18-hour days, it also meant enduring an unprecedented level of personal attacks.

According to a study by the University of Sheffield, the number of abusive tweets sent to candidates - racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-Semitic or in other ways offensive - was up dramatically in 2019.

Find out more

The Next Episode podcast followed seven people standing for election, all of whom kept a record of the abuse they received. Download the episode here.

The researchers registered 158,000 abusive tweets, compared with 31,000 during the election period in 2017. This year 4.5% of replies to the candidates' tweets were abusive, compared to 3.3% at the last election.

"The abuse has become normalised and it doesn't shock me any more," says Andrea Jenkyns, who was re-elected as Conservative MP for Morley and Outwood in West Yorkshire.

She says she has received rape and death threats since she was first elected in 2015. She came off social media for three months after a man rang her office and threatened to rip her face off.

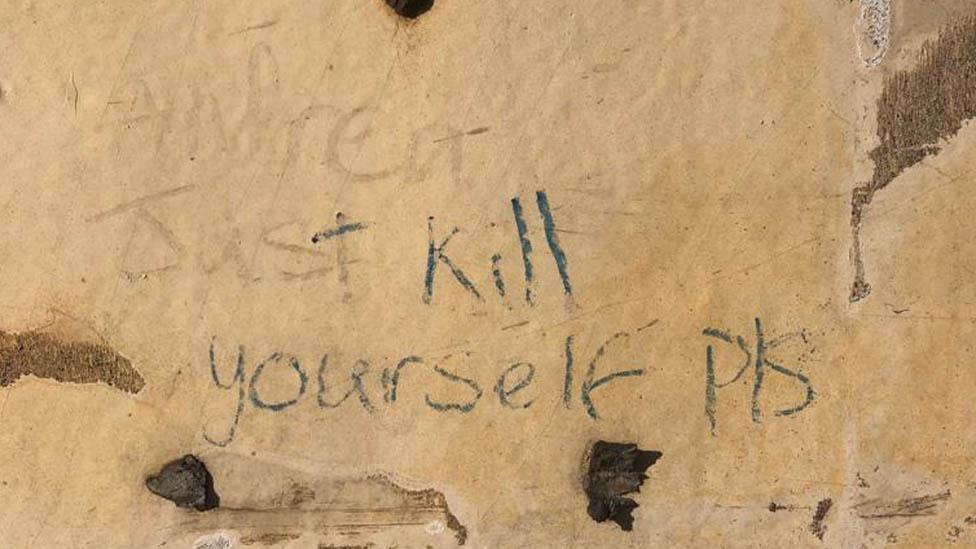

But she says the level of abuse in the most recent general election was worse than in 2015 or 2017. This year, she says, every piece of outdoor signage put up by her campaign was defaced. One of her canvassers was even threatened with a sledgehammer.

Graffiti targeting Andrea Jenkyns

The murder of Batley and Spen MP Jo Cox in 2016 has left many candidates feeling understandably fearful. For the first time, police advised candidates not to engage with abuse online or in person, to block abusers online and to report any intimidation. This was for their own safety, they said.

Some candidates have their own rules, too - they might not go out alone, or after dark, and some carry personal alarms.

Labour's Luke Pollard, the first openly gay MP to represent Plymouth, has his office in the centre of his constituency so it can be easily accessible to constituents. Twice during the election campaign it was vandalised with homophobic graffiti.

Luke Pollard painting over graffiti outside his office

Pollard says that although he was keen for the building "not to look like Fort Knox", he took security advice and had bomb-proof windows installed. The abuse, he says, "kind of eats away at you". Like Andrea Jenkyns, he has a "file of hate" - a collection of all the abusive correspondence received in case it needs to be taken to the police.

But he tries not to let the abusers get to him as "that's what they want."

Charlotte Nichols, 28, who was elected for the first time in Warrington North for Labour, was so frightened by some of the messages she was sent that she called the police.

"I've been called things like 'another southern Labour slag', I've had stuff about how I'm a vile sewer rat, that I'm a traitor," she says. "Probably the most sinister and hurtful one for me personally was someone who sent an anonymous letter to the local Catholic churches to let them know I've had an abortion."

Charlotte Nichols

Nichols, who converted to Judaism in 2014, also faced abuse connected with her religion. "There's a lot of stuff saying how could I be Jewish if I was campaigning on a Saturday? And how can I be Jewish if I'm a Labour Party candidate, when the party has got issues with anti-Semitism?" One person accused of her being a "kapo" - a term that was used for Jewish people who became concentration camp guards.

Sometimes, however, it is the candidates themselves who are accused of contributing to the toxic environment. Nichols was criticised during the campaign when old tweets came to light in which she swore and told one antagonist that she hoped "you lose your virginity".

Nichols acknowledges that, as someone who now holds public office, "I will have to react differently."

But she refuses to apologise for tweeting that a group of Italian football fans pictured giving fascist salutes in Glasgow should "get their heads kicked in". Her Conservative opponent in Warrington North accused her of inciting violence. She responded: "I believe fascism should be physically confronted."

After the 2017 general election, the independent Committee on Standards in Public Life conducted an investigation into abuse of candidates. Its chairman, Lord Jonathan Evans, says that two years later some of its recommendations have yet to be implemented. He's particularly disappointed that the parties have yet to agree to a joint code of conduct.

The current situation is deterring people from entering politics, he believes.

"This is really important to the future of our democracy," he says. "Because if people don't feel confident to stand, or if, as we have seen, some people stand down, then that means we are going to have a less representative and less effective democracy." MPs have told him that they have changed their votes in parliament as a result of "intimidation".

According to the Sheffield University researchers, first-time candidates running in areas they aren't likely to win tend to experience more online abuse than others.

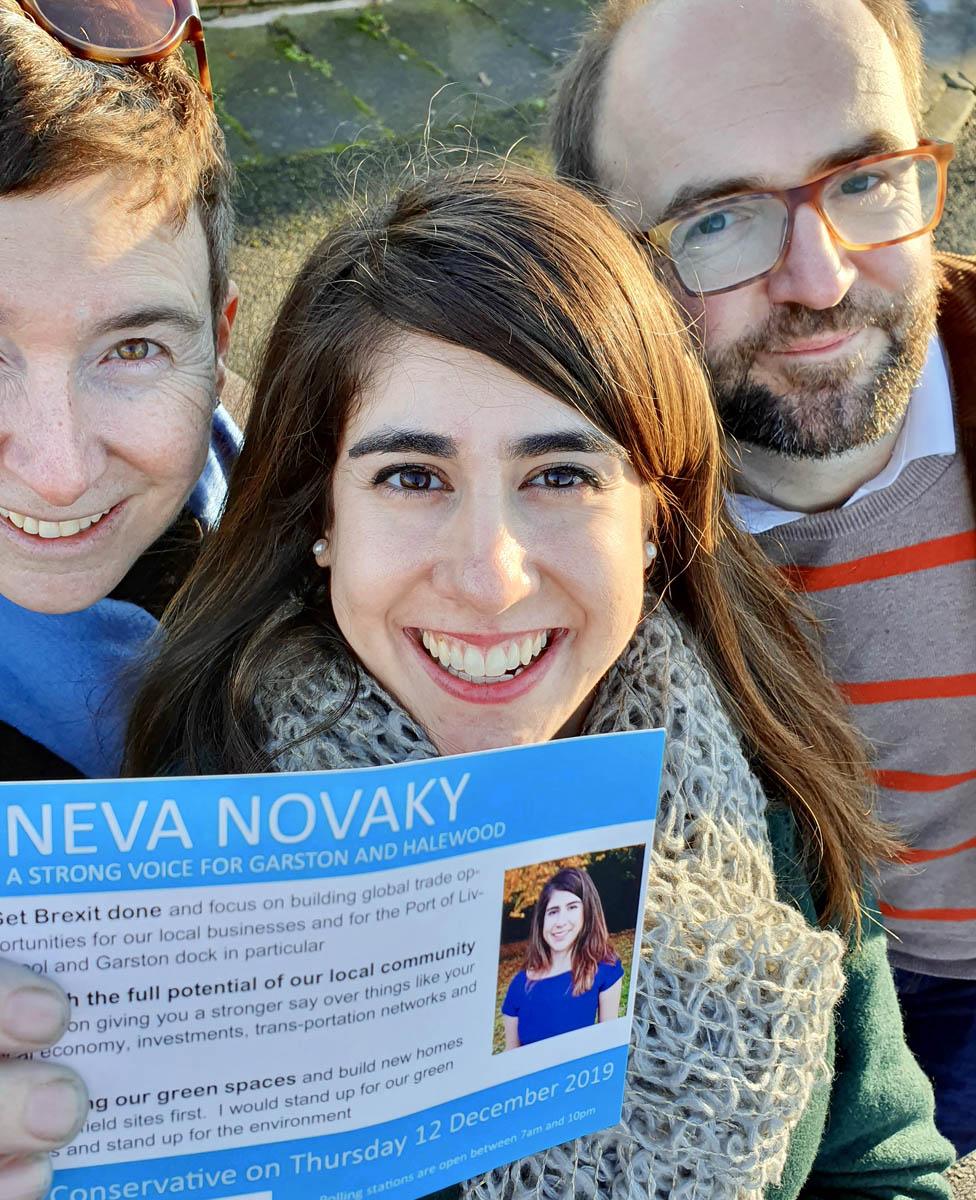

Neva Novaky, 32, says she was taken aback by the vitriol she was subjected to in her first parliamentary campaign for the Conservatives in Garston and Halewood, a safe Labour seat in Merseyside.

"What I was not expecting was the level of animosity and the way that you get a lot of anger and hate directed at you as an individual," she says. People swore at her and told her she was a liar. One of her canvassers was threatened with a shovel, another with a hammer, she says.

But no matter how much abuse they've suffered, candidates still want to go out and campaign.

Julia Ogiehor says the moments when she didn't want to get out of bed or speak to anyone always passed. They "revived me to then get back out there", she says. "I will not stop fighting."

The reporter on the Next Episode podcast was Molly Lynch