'The closest thing on Earth to interplanetary travel'

- Published

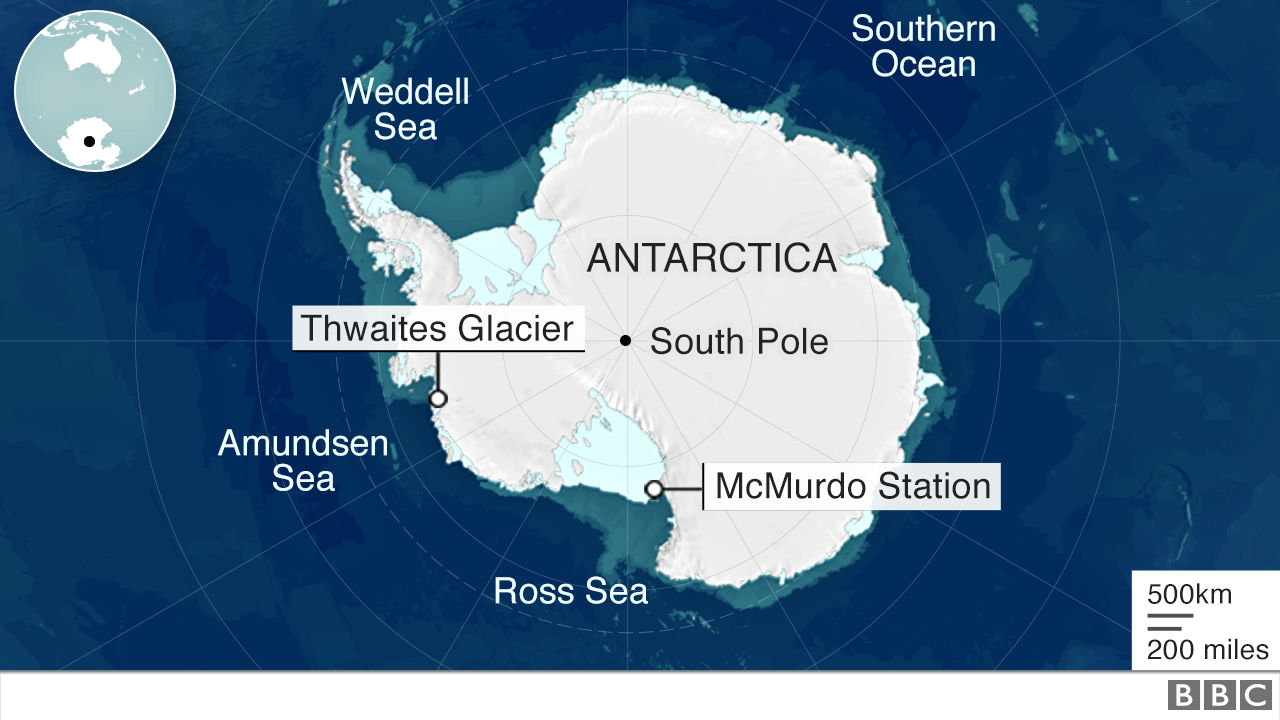

Finding out how fast Antarctic ice is melting is critical to understanding the scale of the climate crisis. The BBC's chief environmental correspondent, Justin Rowlatt, is therefore joining scientists as they check the health of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. But first he has to undergo some checks himself.

We were an hour into the medical examination.

Dr McGovern had asked every conceivable question. He had peered at, measured and squeezed me.

Then there was a pause.

"Now I need to examine your prostate", he says.

"You're kidding," I say.

"I am not," he replies, reaching for a latex glove.

Mount Erebus - the southernmost active volcano on Earth

Don't get me wrong, I understand why men of a certain age should undergo the procedure, I just couldn't see why this should be a condition of going to Antarctica.

But, as I was discovering, everything Antarctic is extreme. Fall ill and dozens of people might have to risk their lives to try and rescue you.

It is the coldest and driest continent, and is also vast - home to 90% of the world's ice.

You're familiar with the marine life here, the penguins, seals and whales, but the largest indigenous land animal is actually a wingless midge.

"Travelling to Antarctica is the closest thing you'll get to interplanetary travel while staying earth-bound," one old Antarctic hand told me when I visited the British Antarctic Survey's HQ in Cambridge.

I had a stack of books about the continent beside me on the long flight to New Zealand.

They are full of tales of the first explorers' epic exertions in the tooth-shattering cold.

They call it the Heroic Age, but it says a lot about Antarctica that the "heroes" we celebrate were more often failures, defeated by this unforgiving place.

Scott didn't come back.

Shackleton did, but on his most famous journey never actually set foot on the continent.

Meanwhile Amundsen, who planted the flag, is regarded by some as a cheat, because he didn't suffer enough.

David Vaughan, the head of science at the British Antarctic Survey, is dismissive of those who come to Antarctica in search of adventure.

"If you want to suffer you can do that just as well in the Lake District," he tells me over coffee in the spring sunshine of our hotel in New Zealand.

The air smells of fresh-mown grass. Birds squabble in the trees. A Christmas tree flashes incongruously in the corner.

David takes another sip of cappuccino.

"You can die of exposure there too, if that's what you want to do."

I'm not heading down south for adventure - but what I'm doing is very adventurous.

I'm here because the ice at the end of the world has begun to stir. Satellite images show the retreat of the mighty Thwaites glacier has begun to accelerate.

Timelapse satellite images of Thwaites Glacier melting

It already accounts for 4% of global sea-level rise.

If Thwaites goes, the world's oceans would rise by over half a metre, but it would almost certainly also precipitate a wider collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet - which could add another three metres or more.

The scientists I'm with want to find out how likely this is to happen and, if it does, when.

But only a handful of people have ever been to Thwaites, one of the most challenging places to reach - let alone work in - in the whole of Antarctica.

It is remote, 1,000 miles from the nearest research station, the glacier is riddled with treacherous crevasses, and the whole region is subject to terrible storms.

By the time the C-17 cargo plane skids to a halt on the Ross Ice Shelf we're already late - snow on the runway has set us back a day.

I walk down the ladder and into a dazzling world of white and blue. The light is refracted into rainbows as it scissors off the ice. It is breathtakingly beautiful but I am entering a world in which time dissolves.

Within days of arriving at McMurdo, the main American research station in Antarctica, I feel as if I have been here for years. It isn't just that the sun never sets, it is also because the 1,000 or so people here are so friendly.

Justin Rowlatt (left) and cameraman Ben Sadd pose with the masked organiser of an Antarctic 10K run, and (right) David Vaughan

Perhaps the vastness of the landscape and vagaries of the weather make co-operation and generosity the default option down here.

I'm piling second helpings on to my plate in the galley - the canteen that serves the base - when a man in overalls and a shaggy beard asks what I'm here for.

"I'm with the Thwaites project," I tell him.

"You mean hurry up and Thwaites?" he says with a laugh.

It turns out not a single flight has made it from McMurdo to our base camp in West Antarctica for days. Three of McMurdo's Hercules planes are broken and there's a nasty weather system barrelling our way.

I help myself to an extra scoop of fries. When I sit back down I discover a fascinating marine biologist has joined our table. She's studying how the extraordinary marine life forms that have evolved in Antarctica's frigid waters respond to changing sea temperatures.

There are worse places to wait than the end of the world, I tell myself.