Belching in a good way: How livestock could learn from Orkney sheep

- Published

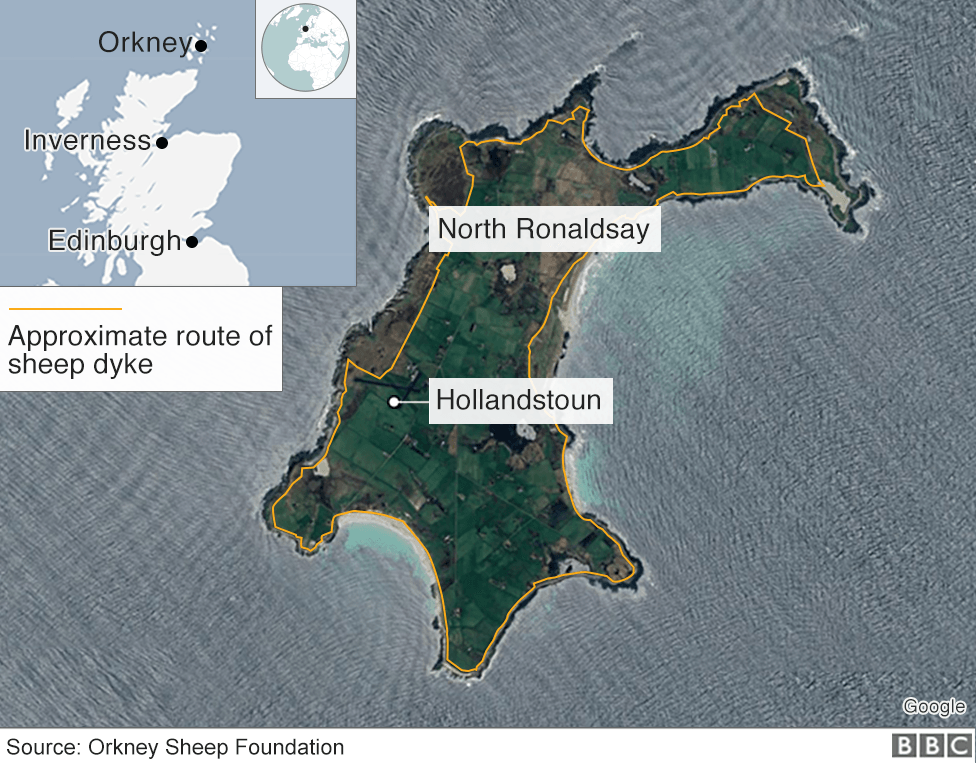

The northernmost Orkney island, North Ronaldsay, is home to just 50 people and 2,000 sheep. Since the 19th Century, when islanders built a stone wall to confine the flock to the shoreline, it has survived on seaweed alone - and it now seems that this special diet could hold the key to greener, more climate-friendly livestock farming.

"It's a bit like doing a jigsaw," laughs Sian Tarrant as she heaves another large stone on to the wall. "Only there are no straight edges and some of these pieces are really heavy."

The wind, which has been viciously squally all morning, punches at our faces and blasts the smaller slates on Sian's rock pile until they shudder and rattle like teeth.

"My contract is for three years," she tells me, securing her flying hair under her bobble hat. "I really hope I can finish repairing the wall by then!"

Twenty-eight-year-old Sian is North Ronaldsay's great hope. Back in the summer, she successfully answered an advertisement to become the island's sheep warden, but shepherding is not her only responsibility - she must also repair the 21km dry stone dyke that circles the island just above the shoreline.

It's this wall that has stopped her flock from eating grass, and made it utterly unique.

"But I will admit," she says, wiping her eyes which the wind is relentlessly needling, "until I started researching I had no idea how special the sheep were."

Dr Kevin Woodbridge, the island's retired GP and member of the Sheep Court - the management body that oversees the flock - has never been in any doubt of this. Short-tailed, small and coloured white, grey or chocolate brown, the sheep are descendants of the most primitive breeds of ruminants, Kevin says, and have been living on the island for thousands of years.

At the sound of our boots on the pebbles, the timorous flock wheels round and shoots off, leaping bits of rope and debris left by the tide. Kevin laughs and tells me, a little self-consciously, that he's sure the sheep are more intelligent than most and certainly more devious.

"I mean, just look at this wild habitat they live in," he says, nodding at the rocky beach and the sulky steel-grey sky with its bulging, herniating clouds. "You have to be pretty adaptable to survive this."

And the sheep certainly have adapted. Since 1832, when the islanders decided to build the 2m-high dyke to keep the sheep from pasture they needed for cows, the flock's diet has been restricted to seaweed foraged from the shore. They are one of only two groups of animals on Earth that exist purely on seaweed; the other is a marine iguana which lives in the Galapagos Islands.

"People think seaweed isn't very nutritious," smiles sheep farmer Alison Duncan, who also runs the Bird Observatory, as we drive round the little island in her electric car, checking up on the sheep. "But we never have to feed the sheep and just have a look at them - they get pretty fat on it, especially in winter when there's lots of fresh seaweed washed up. And the lambs have a pretty good life - we don't send them for slaughter until they're three or four years old."

We park up and trudge over the fields towards the coastline, where the sheep are grazing, our heads low against the buffeting all-prevailing wind. We startle a chunky little woodcock that's sheltering in the long grass and it twitters its indignation shrilly.

Find out more

"The sheep's peculiar diet gives their meat a fuller, more gamey flavour," shouts Alison over the gusts. "And it's really sought after now, not only by local chefs in Orkney but also in big London hotels, and it's quite a delicacy."

In fact, North Ronaldsay mutton was served to the Queen on her Diamond Jubilee and is now in the process of acquiring Protected Geographical Indication status from the EU, like Wensleydale cheese and Jersey royal potatoes.

But lately the sheep have been enjoying even greater fame. Studies from the US, New Zealand and Australia have shown that livestock that have some seaweed in their diets belch far less methane than animals fed on grass or general feed. And since methane is a greenhouse gas that has a warming effect almost 30 times as powerful as that of carbon dioxide, the solely seaweed-eating North Ronaldsay sheep could provide an answer to greener farming.

At Shotts, outside Glasgow, David Beattie takes me to the see the giant bins being filled at the Davidson's Animal Feeds mill. David will be spending the next three years studying how protein-rich seaweed could be introduced into general livestock feed. Part of a Knowledge Transfer Partnership which couples academia with industry, David is dividing his time between the factory floor at Davidson's and his laboratory at the James Hutton Institute in Dundee.

"You'd be amazed how picky animals are about their food," he explains, as we examine a new mix of sugary-smelling sheep pellets the mill has just produced. "We have to put molasses into the mix to get the animals to eat it - otherwise they just pick out the bits they like and leave the rest. So, it's quite a task to introduce seaweed into the feed and to make sure it's still protein-rich and of top quality."

In a year, a cow produces about the same greenhouse effect as a car that burns 1,000 litres of petrol, so it's fairly evident how beneficial it would be to reduce livestock's carbon hoof-print simply by altering their diet. Experiments have shown that carbon dioxide as well as methane emissions are lowered when seaweed is introduced into feed. And if he succeeds in creating a nutritious seaweed blend that's palatable to ordinary livestock there would be other environmental benefits too, including being able to source more animal feed locally and sustainably.

"A large proportion of the ingredients we put into animal feeds in the UK at the moment are sourced from across the world, like oil seed from South America," says David, showing me the empty fleet of lorries waiting to take the giant sacks of pellets to farms across the UK. "This clearly has negative implications for the environment both in terms of farming methods to harvest that crop but also in terms of transportation. If we could identify a seaweed variant that could substitute oil seed, it would have a huge environmental benefit."

While the North Ronaldsay sheep have thrived over the centuries, the islanders have struggled.

The island used to host a profitable seaweed business, harvesting two varieties of kelp - one known as "tangles" - which were used in the production of iodine and other chemicals.

But last century it was discovered that it was cheaper to source the seaweed from South America. After that the island's population dwindled dramatically from 500 to just 50 today.

David Beattie hopes that his research will help Scotland to re-establish commercial seaweed farming, creating jobs and revitalising coastal towns.

"Can you imagine the benefits if we could introduce seaweed into a supply chain as big as the livestock industry?" he asks.

He reminds me that seaweed, since it is grown in the sea, needs neither fresh water nor fertiliser and that, potentially, fields currently used for growing crops to put into animal feed could be reclaimed to grow food for human consumption. And one of Scotland's other big industries, salmon farming, could also benefit, David adds. Growing seaweed close to the farms helps protect the fish from sea lice - a major problem for salmon farmers - while the nitrogen excreted by the fish helps the seaweed grow.

"So, I really do think we stand to learn a lot from the seaweed-eating North Ronaldsay sheep," he says.

The arrival on the island of Sian the sheep warden a few weeks ago was critically important partly because of the damage to the beautiful dry stone dyke caused by brutal storms and rip tides which battered the island's coastline in 2012 and 2014.

Under the rules of the Sheep Court, it's up to the islanders who own the flock to repair any damage to the wall, which is listed Category A by Historic Scotland. But with a dwindling and ageing resident population, that's no longer possible.

"That's where I come in," laughs Sian good-naturedly, waving her spade. "The young blood! I'm the great hope to make sure the sheep are confined to the shore and the seaweed!"

Worryingly, there have been several reports recently of "loopers", escapee sheep who have spotted a gap or a partially tumbled-down bit of wall and leapt over it, straying on to the rich grasslands on the forbidden side. Although ewes with newborn lambs are deliberately brought briefly on to the grass in the summer - the males, which are sent for slaughter, are never permitted to venture on to pasture - the sheep's stomachs are no longer adapted to grass and they risk copper poisoning if they eat too much.

Just then we spot a sly looper skulking close to the wall. It's on the unauthorised side, its eyes darting towards the prohibited patch of green near our car. Alison finds a torn oil skin the sea has dumped on the shingles and prepares to try to catch it.

"Then we really have to work out how it got in," she tells Sian, the novice sheep warden. "We will have to block up that entry point because as soon as a sheep finds a gap, he will tell his friends and before you know it, they're all on the grass or in your garden!" She laughs. "You see, sheep are very curious animals and for them, the grass is always greener on the other side!"

With amazing matador skill using the oil skin as a shield (Sian insists modestly that it's beginner's luck) the Houdini sheep is recaptured by the pair and after Alison examines his teeth (it turns out he doesn't have any, due to advanced age), together the women heave him on top of the dry stone wall where he teeters for a moment, as if weighing up his options, before he finally jumps back on to the beach side and gallops off on his spindly legs towards the waiting flock.

We walk away from the beach and towards the old lighthouse where the retired GP and sheep owner, Kevin Woodbridge, shows me around the island's mill. Here the sheep's wool with its beautiful muted colours is spun into beanies, fleecy jumpers and soft yarn. The mill currently employs three people but is set to expand into new premises due to increasing demand for genuine North Ronaldsay garments.

Kevin Woodbridge (left) and a member of staff at the mill

"I've always thought of our sheep as an organic product," Kevin says thoughtfully, when I ask him how he feels about the discovery that the island's sheep could help us reduce greenhouse gas emissions from livestock. We look out over the beach where a small group of sheep are enthusiastically grazing on a fresh crop of moist seaweed the bigger waves have just delivered.

"We know we need to reduce our red meat consumption and if we can reduce the impact of red meat production as well, then that's really good news for the sheep."

Alison and I sit in the warm breakfast room at the Bird Observatory watching a pair of hen harriers intently searching the fields for food.

"We would be really proud if scientists could learn from how our sheep are digesting seaweed and producing less methane," Alison tells me, putting down her binoculars. "That could help all farmers reduce their carbon footprint and could give us a good bit of publicity for selling the sheep elsewhere."

It's getting dark now and having temporarily patched up the section of wall over which the looper made his bid for freedom, sheep warden Sian Tarrant decides to call it a day and cycle home.

Opposite her house the little school stands quiet and empty. No children have been raised here for many years.

I comment that I've heard that some islanders are pinning their hopes on her to change that.

"Yes, that has been mentioned to me!" she agrees, laughing. "But maybe let's sort the sheep problem first!"

Against the brooding, dark skyline, a cluster of sheep huddle together on a crop of rock as the wind continues to hurl along the length of the coastline. They scour the heaving waves patiently, waiting for the bigger ones to deliver their next seaweed dinner, which they will digest in their longstanding, idiosyncratic methane-modified way.

Far away on the mainland, scientist David Beattie is experimenting with the nutritional make up of seaweed variants, and writing up notes for the speeches he will deliver at forthcoming European conferences on greener farming.

As they graze in the moonlight, the North Ronaldsay sheep silently belch their satisfaction. Ruminant recognition doesn't get much better than this.

Photographs by Fionn McArthur, Start Point Media, unless otherwise specified

You may also be interested in:

Orkney has been invaded by geese. The numbers are now so huge, and the damage so great, that permission has been granted for the wild birds to be shot - and eaten, reports the BBC's Emma Jane Kirby.