'Why can't I find an Afro-Caribbean egg donor?'

- Published

When Natasha and her husband had difficulty conceiving a child, doctors gave her two pieces of bad news. The first was that she would need to find a donor egg. The second was that Afro-Caribbean eggs are rarely donated. But she hasn't given up hope.

Natasha is 38 and is struggling to have a baby.

She got married in 2011, and started trying to conceive immediately. Eventually it became clear there was a problem.

"I actually had four rounds of IVF treatment and obviously none of them were successful. And after the third round the doctor said, 'We doubt that your eggs are going to be any good and you probably need to consider going down the egg donation route.' And she literally got up from her seat and said, 'I'll give you some time with your husband to discuss,' and she walked out the room. And that was it."

Natasha's next step was to call organisations that might help her obtain a donor egg. One was a donation bank.

"They basically said, 'We're going to have to be honest with you, but we don't have many black Afro-Caribbean egg donors come forward.' They told me straight and I appreciated the honesty rather than being sent on a goose chase."

Natasha then cast her net further afield. A clinic in Spain offered her an egg donated by an African. Many might think this was not a bad solution, but Natasha was not sure it would be right for her.

"My heritage is Caribbean. My grandparents on both sides of the family are both from the Caribbean… it was important to me to at least have some cultural connection with the child, and I felt that if it was from a different heritage, I may not…"

She also felt that her family, which she says "has a big hang-up about who looks like who", might discriminate against a child that they knew had come from a donor.

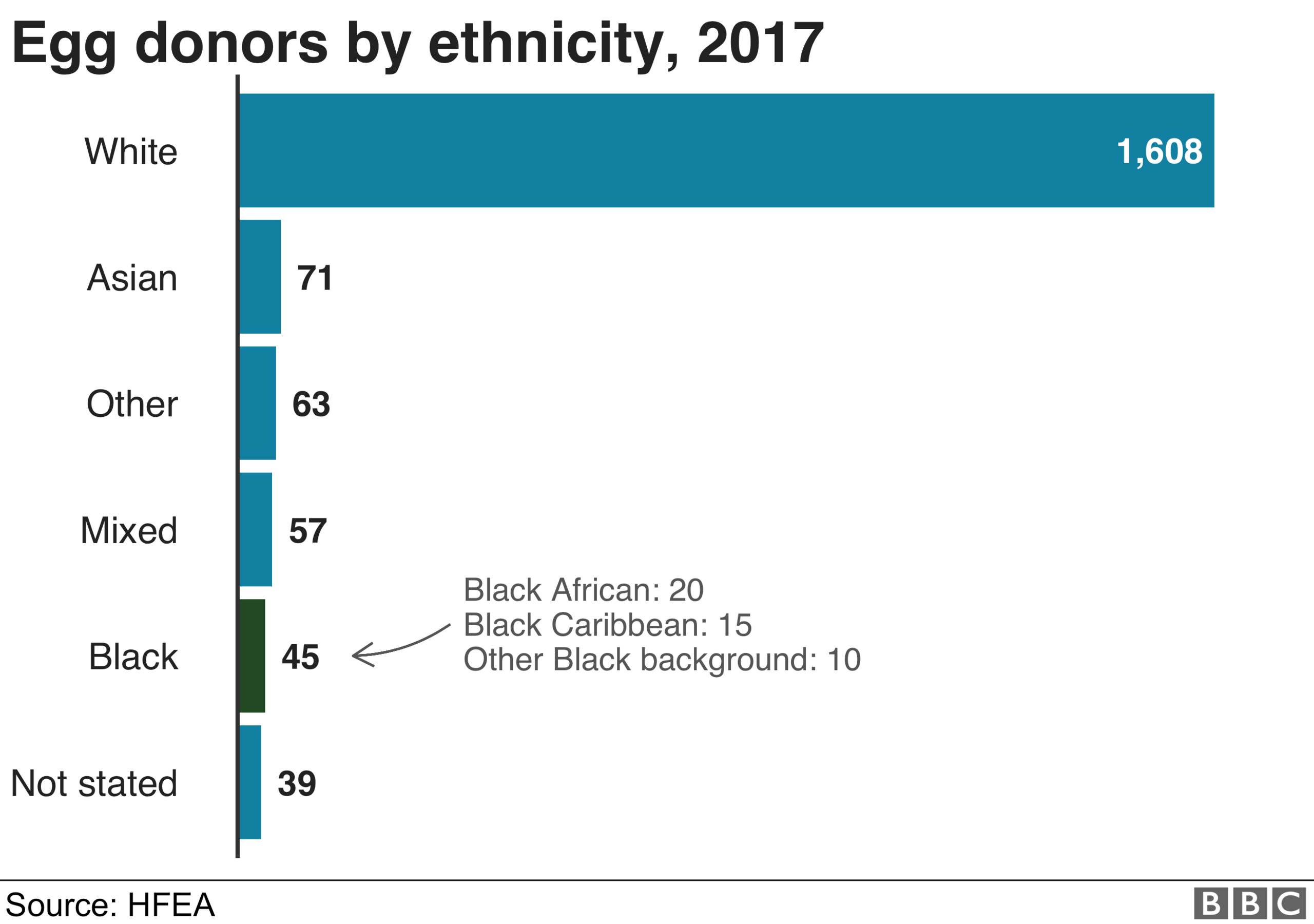

In 2017, about 1,900 individual donors donated eggs in the UK. Of these only 15 were categorised as "Black Caribbean". Twenty were Black African. The vast majority - 1,608 - were White.

As Black Caribbeans make up 1.1% of the population according to the 2011 census, you might expect 21 out of the 1,900 donors to have come from this group. Black Africans, meanwhile, make up 1.8%, so if 2017's donor eggs had been evenly distributed by race, there would have been 34.

Dr Edmond Edi-Osagie, a reproductive medicine specialist in Cheshire says that there is "something cultural within the black community" that makes women reluctant to donate eggs.

"Any time I see an Afro-Caribbean woman over the age of 35 who walks through my clinic, the first thing I think about is, 'Are they going to need donor eggs?' My heart really sinks, because I know that it's going to be a really difficult battle if they are," he says.

He also finds that Afro-Caribbean women are more likely to need donor eggs, than white women of a similar age.

"The reasons for that we're still not very clear about, and there are many plausible reasons, but that's what we are finding anecdotally."

Edi-Osagie has been to a number of black organisations and black churches to talk about the lack of donor eggs and the message always goes down well, he says.

"I get a line of people who wait to speak to me to give me their contact details and then I get my staff, over the following weeks, to try to contact all of those people - and unfortunately, almost invariably that's where the trail ends," he says.

Find out more:

Listen to Natasha: Trying to find a black egg donor on Monday 13 January from 20:00

Part of the series My Name Is... on BBC Radio 4

Natasha thinks that one reason so few eggs are donated could be that women don't know there is a shortage.

"There's no awareness, no-one's printed any leaflets - it's not sitting in the waiting rooms of any hospitals," she says.

She also thinks it's a taboo subject that is rarely discussed in the black community.

If the subject is ever mentioned, it's a throwaway comment like, "Sandra up the road, she cannot have a baby," Natasha says.

"It's never taken seriously about how that person must be feeling or what support they may need. It's just not a topic that's ever brought up and yes it does need to change, it really does," she says. "Especially because women, no matter what cultural background, are having children later. So I know I'm not going to be the only person that has gone through this."

Natasha admits she hasn't told her own family about her fertility problems.

In fact, she doesn't even think her husband is aware of the toll they are taking on her.

"He is a very practical man… all on my own."

She says she has to "wear a mask" so that people don't see how she is feeling when something they've said makes her emotions almost brim over.

This doesn't surprise counselling psychotherapist Helen George who, in the course of her research into why older Afro-Caribbean women rarely seek therapy, has heard many say, "You don't talk your business to people."

She's keen to encourage the black community to talk more about infertility, but also to encourage the health system to discuss infertility in a more inclusive way.

"I feel that when we look at the whole landscape of infertility and the services out there, you know, it doesn't represent us," she says.

She had noticed online an event in London called Fertility Fest, which describes itself as "the world's first arts festival dedicated to fertility, infertility, the science of making babies and modern families", and found herself thinking, "it's kind of all white people".

But in 2019 it ran a session on race, religion and reproduction, and she took part.

"The taboo, the stigma, not talking about it in communities, that all came out," she says. "Religion was another one… religion in terms of being angry at God, being angry at not getting what they want."

But she came away with the feeling that the conversation had started. "There was a room full of people of colour all talking about it. People are finding their voice now."

You may also be interested in:

When Elaine Chong found out that there was a shortage of women of colour donating eggs, she decided to do something about it.

Natasha is on a waiting list for an Afro-Caribbean donated egg. She doesn't know how long she will have to wait. "I need to build up my inner strength to be able to go forward with this again," she says. "I know my age is against me."

She also wants to start raising awareness about this issue in her community in the hope that this will encourage more women to donate eggs - not just for her benefit but for the general good.

It frustrates her that the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, which is aware of the shortage of certain eggs doesn't try to alert the public to this fact. The HFEA points out that it is a regulator, and that this role doesn't fall within its regulatory charter.

And she thinks that more could be done to point out to women that although donating an egg is not a simple procedure - it involves numerous medical tests and you have to inject yourself with hormones twice a day - donors are compensated with a one-off payment of £750.

"I feel that I need to start the ball rolling and maybe being that voice that is knocking on the door, and actually steering this conversation further and making people more aware that this is a problem - because I'm sure that most people wouldn't even consider that this problem even exists."

Nadia Akingbule, external is on Instagram