'My father, the killer'

- Published

"Did you actually kill hundreds of people, Dad?" It's not a question that many people feel the need to ask their parents. But for a group of daughters and sons in Argentina, it became one they could not ignore.

When the phone rang in Analía Kalinec's Buenos Aires home on a wintry August afternoon, she had no reason to suspect the call would end up blowing her family apart.

"It was my mum. 'Look, don't freak out but Daddy is in jail,' she told me. 'But don't worry, this is just politics.' Until that phone call, I had never ever linked my dad's job to the dictatorship. Not even remotely…"

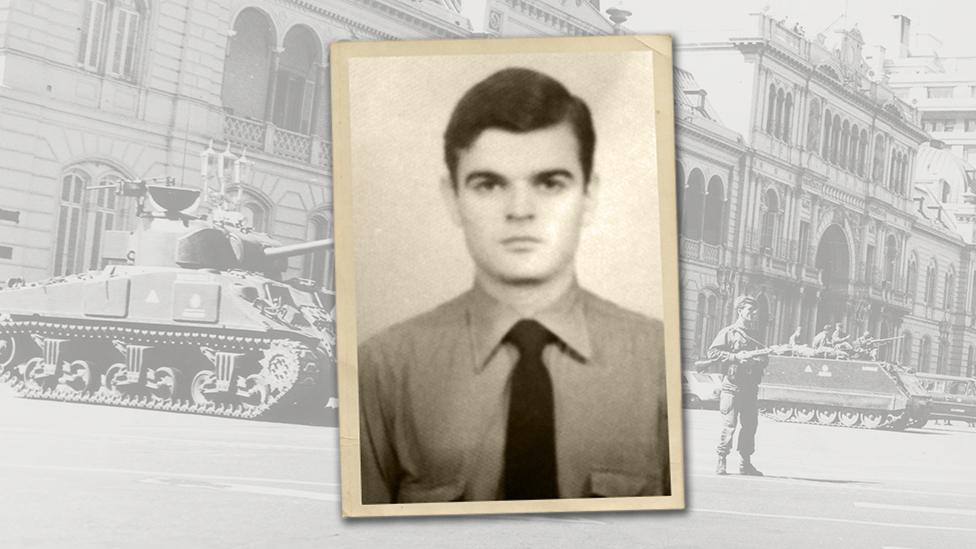

Analía's father is Eduardo Emilio Kalinec, a former police officer who served under the brutal military junta that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983.

He was accused of some of the worst human rights violations in the country's recent past - over 180 cases of abduction, torture and murder committed in the regime's secret detention camps.

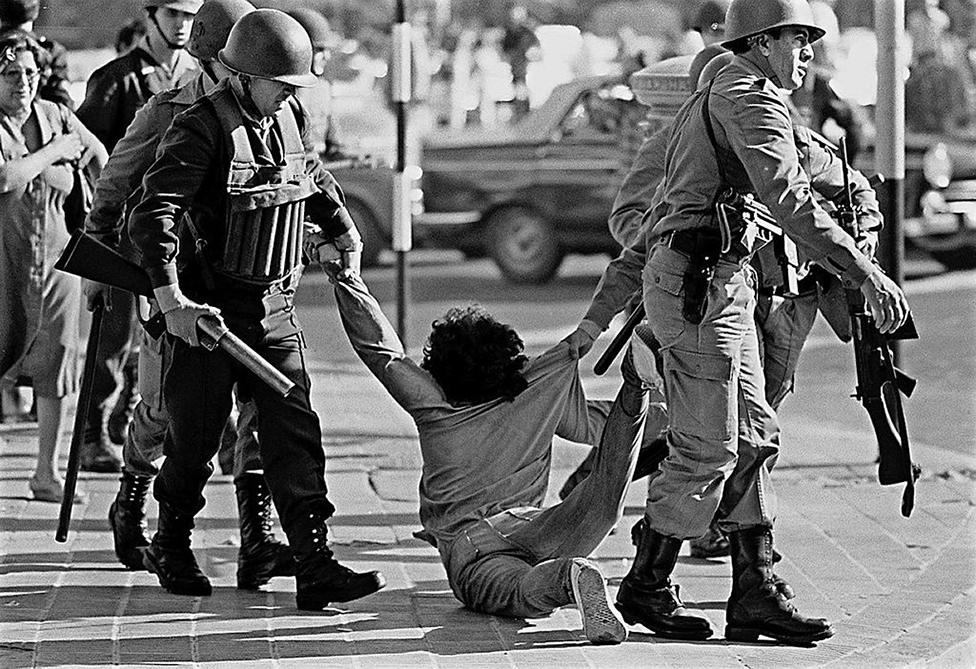

For the seven years it held power, the military government targeted political dissidents - communists, socialists, union leaders, students and artists. Up to 30,000 were "disappeared" after being kidnapped and illegally imprisoned by security officials like Kalinec.

But Analía hadn't got even a hint of her father's well-kept secrets until 2005, when she was 25, and received that call from her mum.

Kalinec was taken into custody and, despite his wife's initial optimism, was never released. In 2010, he was given a life sentence for crimes against humanity.

"He asked me: 'Do you think I'm a monster?'" Analía says. "What did he expect me to say? It was my beloved dad, I was so close to him… I was stunned."

Paula (who asked the BBC not to use her full name) also experienced a moment of revelation about her father.

When she was 14 he took her and her brother to a cafe, and told them he had been an undercover cop. Later she realised he had been a spy, infiltrating left-wing groups and identifying people to be seized by the regime.

"Since it clicked in my head that what I knew about the dictatorship had been done by my father, or that he worked for them, I've been feeling ashamed and guilty as if I were an accomplice," says Paula.

"Now I have this knowledge and there's nothing I can do. It's like I'm keeping a secret I don't want to keep."

It took these daughters years to understand and come to terms with their family history, but recently they have felt the urge to speak out.

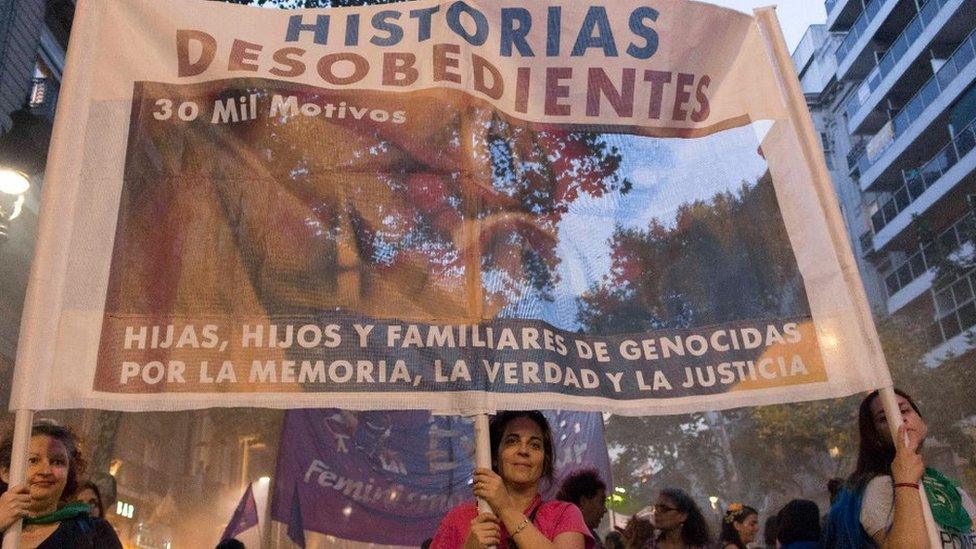

They are part of a group of the "sons, daughters and relatives of the perpetrators of genocide", as they call themselves. They publicly condemn their fathers and are often ostracised by their families as a result.

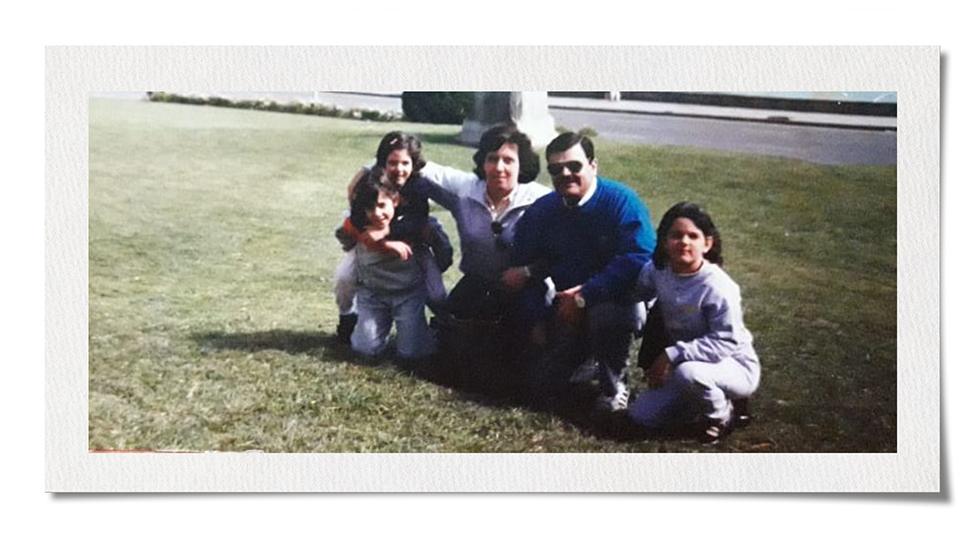

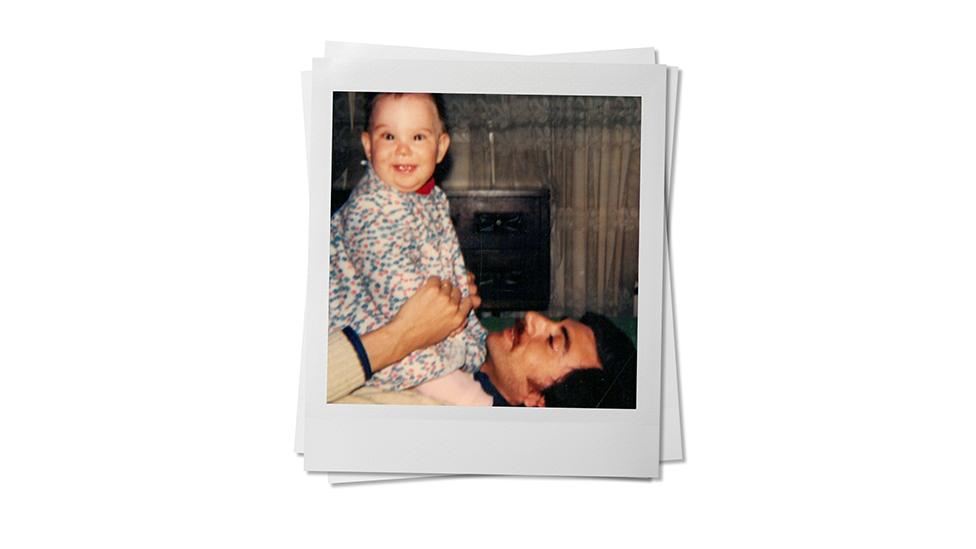

Analía Kalinec, a psychologist and school teacher was born in 1980, in the middle of the junta's battle against supporters of the left. Her memories of her policeman father mostly date from after this period - she remembers him cooking barbecues, taking his daughters to the sports club and on fishing trips.

She and her three sisters all married young and weren't interested in politics.

The day after the phone call from her mum, she remembers, they went to visit her dad in prison.

"When we spoke to him, he just said 'Don't believe what they will say about me, it's all a bunch of lies,'" she says.

He told the family he had nothing to apologise for, that he had been fighting a "war", and that he was now being persecuted by "lefties" intent on revenge.

"I didn't understand a word," says Analía.

For Analía the dictatorship was a thing of the past, and for the first couple of years after her father's arrest, she lived in denial.

"I supported the mothers and grandmother of Plaza de Mayo who were campaigning for their disappeared loved ones," she says. "All good, but my father had nothing to do with any of that. I still believed it must have been an error… It was when the trial started that I realised things were not quite as my father had been telling us."

Analía came face to face with her father's past when she started to read the case files. Over 800 pages filled with stark accounts of the terror he had inflicted, in the voices of the survivors

"I read the descriptions of those concentration camps where the military kept the people they abducted. It was like a map and I had to place my dad in it, which was unbearable," she says.

The victims didn't know Kalinec by his real name. In the clandestine prisons where he worked, he went by an alias, as most did to conceal their real identity - "Doctor K".

"I knew they called him that because he once told my grandma, and when I asked him where the nickname came from he told me it was because he was always very proper and looked like a lawyer, and here we address lawyers as doctors. But it may also be because he was 'the doctor' in the torture chamber that they called 'the operating theatre'."

Analía finally confronted her father in his jail cell.

Police make an arrest in Buenos Aires, 1982

"And when I did that, I found a very angry man who tried to justify the unjustifiable. And in so doing, he confirmed my worst suspicions. That he had personally taken part in it all. It was," she pauses, searching for the right word, "mind-blowing. Totally mind-blowing."

Having a loving relationship with the man, and many happy childhood memories made things harder, says Analía.

"At first I needed to disassociate. I used to say, 'Well, on one side there's my dad and on the other side there's the torturer.' I needed that, or else my head would have exploded. But then I realised that it is in fact the same person. It is always the same person."

Dozens of witnesses in the trials identified Eduardo Kalinec as a participant in interrogations and torture sessions in three different clandestine detention centres.

They described him as a young man - he was then in his mid-20s - with a high-pitched voice, short and brawny, with a thick neck and a moustache.

He was "feared inside" and "of a very cruel character", according to court testimonies of those who survived. Most didn't - a majority of prisoners remain "disappeared" to this day and are presumed murdered.

Ana María Careaga was 16 years old and three months pregnant when she was taken. She remembers that "Doctor K" kicked her when he saw her in the bathroom area. On one occasion he got angry with her for not having revealed to her captors that she was pregnant. "Do you want me to open your legs and make you abort?" he yelled.

There were some 600 clandestine prisons across the country - this one in Buenos Aires was known as El Olimpo

Miguel D'Agostino also identified Kalinec as one of three men who tortured him for five days in a row with an electric prod in the so-called "operating theatre" of the secret prison where he was held for almost a year.

Delia Barrera was 22 when she was taken from her home in a raid - kidnapped at gunpoint by a group of men and taken to El Atlético, the secret prison where Kalinec was based at the time.

"I hear voices around me, as I am blindfolded," Barrera tells the BBC. "They get me naked and strap me to a metal bed frame. And they start with the electric shocks. They blame me for placing a bomb in a police station, which I hadn't done, and they want names of fellow militants. It goes on and on…" she remembers.

She met Kalinec on one occasion during her 92-day detention when her blindfold was not very tight. She assumed "Doctor K" was a medical doctor - and says he did inform her she had broken ribs.

"I could peer at his face from underneath. It's a face I could never forget. When, during the trial, the judge asked me if I could identify any of the accused, I said, 'There he is, Doctor K.'"

The year-long trial that led to Kalinec's life sentence in December 2010, was part of a historical reckoning that is still going on in Argentina, almost four decades after the dictatorship came to an end.

More than 1,000 former military and police officers convicted of human rights abuses have received hefty sentences, and some 370 cases are still working their way through the Argentine judicial system.

Kalinec during the trial

But not all those who took part in the state-organised repression are brought to justice. In many cases, there is simply not enough evidence to hold them accountable - as with Paula's father.

"I know what he did because he told me," she says. "I know he was part of it because he told me. And he was full of pride, he felt like a hero."

Until this point, she had believed her father was a lawyer. She had never seen him in police uniform.

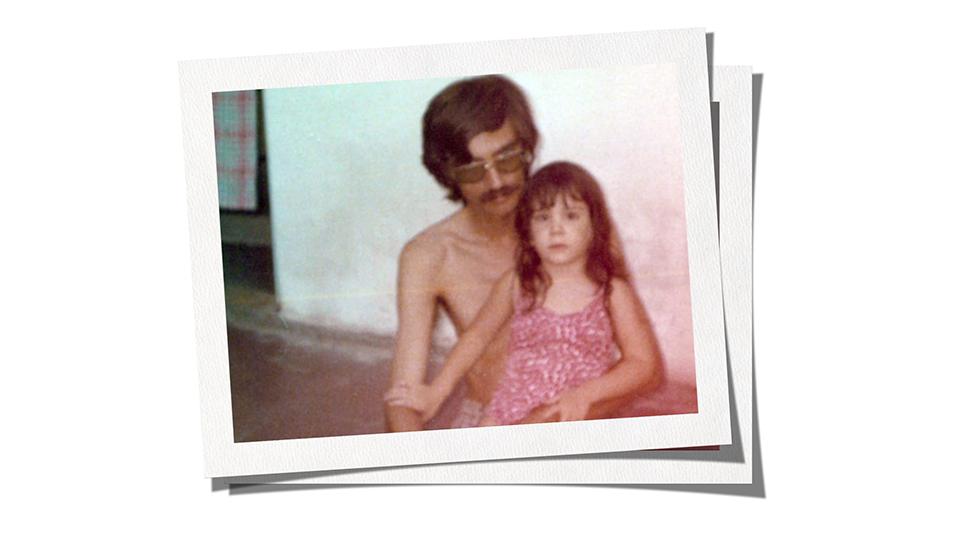

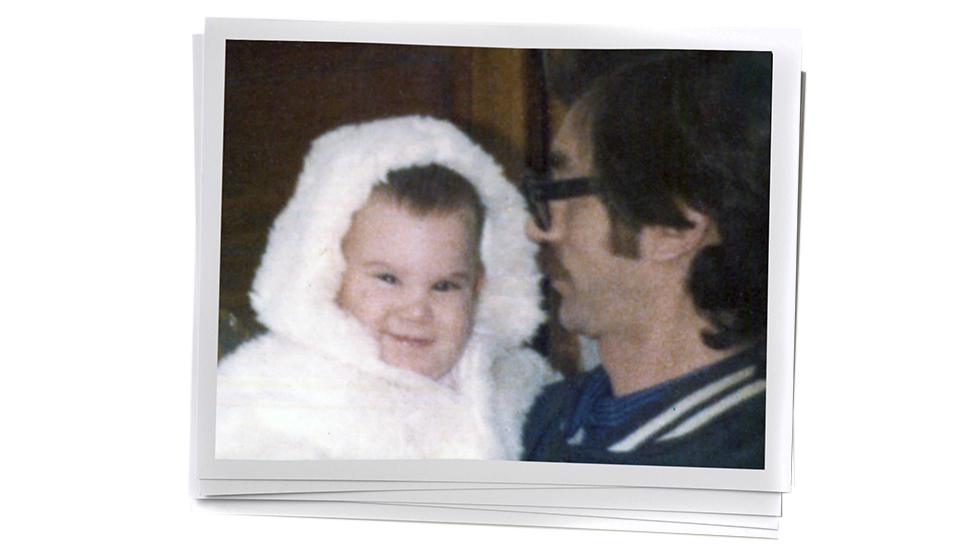

"He was in his 20s then and, for photos I had at home, he didn't look the part of a policeman. He had long hair, wore trendy big-collared shirts… he looked like any young guy from the 1970s."

But in time Paula connected the dots, and worked out that he had been picking out people to be captured and taken away to one of the clandestine centres.

Just like Analía, Paula then confronted him.

"I told him, 'You don't torture people. I don't care if they did something or not. Don't torture people!' And I had this conversation many times over."

Her father would reply that the authorities were tackling "terrorists" and that "the communists were coming". Paula says she doesn't know how much blood her father had on his hands, but he never showed repentance.

"He was a necessary cog in the machine of terror. He said the crimes had to be committed - and he never called them crimes, he called them 'actions'."

Ten years after making the discovery, once her mother had died, Paula cut all ties with her father.

In late 2019 she heard he had been taken to hospital after a severe stroke and wondered whether she should go to visit him.

She didn't. And when he died she didn't go to the funeral.

"I thought it would be disrespectful to attend the funeral for the people who actually loved him. But also, there was a part of me that had already grieved the absence of my father in my life. So I didn't really have the need."

A few years ago, Analía and Paula found each other - and a number of other children of military and police officers who also condemned their fathers' actions.

It didn't happen by chance. It was triggered by a Supreme Court ruling in 2017, during the centre-right government of President Mauricio Macri, that could have led to the early release of hundreds of human rights abusers, Eduardo Kalinec among them.

Half a million protesters took to the streets, demanding the decision be overturned - and it was.

"The fact that my dad is imprisoned speaks highly of Argentine society. I felt I needed to break the silence. I wanted to say, 'Let's be clear, there is no turning back,'" says Analía. "We want to make sure our fathers pay for their crimes."

Liliana Furió (left) co-founded Disobedient Stories, together with Analía Kalinec

Analía published her thoughts in a manifesto on Facebook. Other sons and daughters read it.

"And it all started from there… We got in touch, we met up. We said, 'This is so hard to bear alone.' We decided to come together and take part in demonstrations. The first time there were four of us, all women, with such energy and enthusiasm."

They called themselves Disobedient Stories, because they are breaking the family rule of silence.

Most long ago stopped seeing their fathers and many, like Analía, have siblings who will no longer talk to them.

"I was so happy to find others like me, I knew I couldn't be the only one!" says Paula. "They understood me in ways nobody else could."

Paula (centre) and Analía on the Day of Memory march in 2019

She says she hadn't been able to talk to anyone about her father, except her therapist, and that acquiring the ability to stand up and speak out after 23 years of silence was a tremendous release.

The now 80-strong group - made up mostly of women - meets weekly. They eat together, discuss politics and their feelings and plan public appearances.

One of their campaigns centres on the refusal of their fathers to confess to their crimes, and helping prosecutors to convict other guilty men.

"I am still waiting for him to talk. I know my father has information about his victims," says Analía. "Unlike other officials, who are too old or senile, my dad is lucid and has a prodigious memory. And knowing that he chooses not to say, and that his complicit silence is still causing pain and damage, is something that really hurts me."

Since their fathers won't speak, the members of Disobedient Stories want the Argentine penal code to be amended to allow children to testify in court against parents in cases of crimes against humanity. Often the case against the men is a jigsaw that the children could help to put together with their family knowledge - for example, Analía's awareness that her father was known at work as "Doctor K". Another member heard many details from his father about the practice of throwing people alive from helicopters into the ocean but has been unable to testify in court.

"Socially, speaking against your father is strongly condemned in this patriarchal society. Your father, your blood. Well, what if your father is a torturer or a rapist or a thief? You cannot say anything?" asks Analía.

"People don't even question that. Well, maybe it's time we do."

In 2018, Disobedient Stories took to the streets for National Memory Day - 24 March, the anniversary of the military coup. Their multi-coloured banner read, "We are the relatives of the perpetrators of genocide."

Analía says people gave them puzzled looks. A few burst into tears, though many more applauded.

"It was the first time that a group of relatives of the perpetrators were taking such public stance," she says.

Analía (centre) came together with other relatives in the Disobedient Stories collective

Yet not everyone is ready for their activism. The collective is an uncomfortable presence for some of the victims' relatives and survivors.

"These 'disobedient' sons and daughters had plenty of opportunities to speak up - and they didn't do it earlier, why is that?" questioned survivor Delia Barrera, when interviewed by the BBC in 2019.

She said she didn't trust them, particularly those who said they still loved their father, after everything he did.

"Tell me you don't love him," she said, "and maybe that's a different story."

Delia Barrera has testified in several trials - she was 22 when kidnapped with her husband, Hugo, who remains "disappeared"

For the sons and daughters of convicted criminals, it is often more complicated.

"Look, I ask myself that all the time, we always discuss it in the collective," says Analía. "How do you erase affection? How do you delete your good memories? How can you decide to love or not to love? I refuse to give up on this father that I once loved, there's a part of me that wants to hold on to that. So I live with these contradictions."

Some have gone further though, calling themselves "ex-daughters" or putting in a formal request to change their surname.

"I think it is a very personal decision to make, but for me it wouldn't change anything. I am not going to give my father the right to keep the surname. It is also MY surname, my family, my history", says Analía.

Paula agrees.

"You took a lot of things from a lot of people," she told her father, when he was alive. "You're not taking my name. You tainted it. You smudged it. I'm going to clean it."

Since his death, she has taken a step back from the collective, but says her "ethical stance in relation to the dictatorship, and the role of my father in it, remains unchanged".

"I still feel a responsibility to speak up and maybe wake up other people, both in Argentina and around the world, regardless of the relationship they may have with the perpetrator. So that fight won't ever be over."

Family photographs courtesy of Analía Kalinec and Paula

Listen online to the documentary My Father the Killer or download the podcast