Coronavirus: The 'good outcome' that never was

- Published

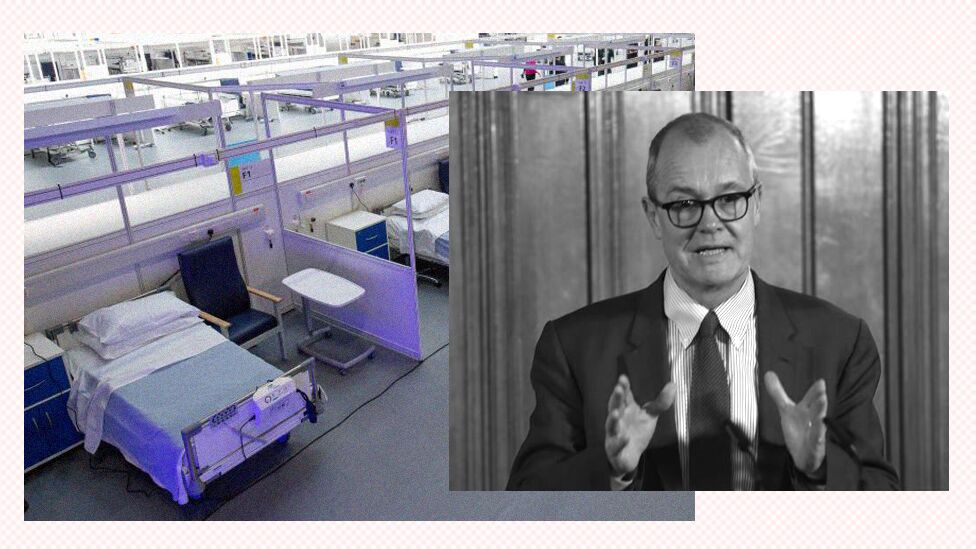

The UK's official tally of coronavirus-related deaths has passed 20,000 - a figure the chief scientist once said would represent a "good outcome". It's a huge number and hard to visualise. How can we grasp the scale of this loss?

On the afternoon of 17 March 2020, in a Westminster committee room, Sir Patrick Vallance leaned forward in his chair.

Back then, the number of people confirmed to have died in the UK after contracting Covid-19 stood at 71. Stricter measures had just been introduced to tackle the virus. Sir Patrick, the government's chief scientific adviser, was asked if the final tally of British deaths could be limited to 20,000 or below. That would, he told MPs, be "a good outcome".

Eleven days later, with the official death tally now at 1,091, Stephen Powis, NHS England's medical director, repeated Sir Patrick's benchmark. "If we can keep deaths below 20,000," he told the daily Downing Street media briefing, "we will have done very well."

Already - less than six weeks after Sir Patrick's statement, and a month on from Stephen Powis's - the 20,000 figure has been surpassed. No-one can predict what the final number of deaths will be when the pandemic is over, or what will ultimately be considered the benchmark for a "good" outcome.

Nonetheless, the 20,000 figure serves as a landmark and passing it has grim resonance.

Of course, the government is only recording hospital cases where a person dies with the coronavirus infection in their body. Other estimates, external have been much higher.

"The daily official tally gives a very limited picture of the impact of the virus - if we take into account reporting delays and deaths outside hospital, we probably passed 20,000 deaths attributed to Covid-19 a week ago," says Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter of the University of Cambridge. "There are also many thousands of extra deaths in the community that have not been attributed to Covid-19, either through caution in putting it on the death certificate, or reluctance to send people to hospital."

And even though a ceiling of 20,000 fatalities was considered a hopeful scenario, it was only ever so in the most the limited sense.

A tally on that scale would still be "horrible", Sir Patrick told the Commons Health Select Committee back on 17 March. It would mean an enormous number of deaths. "Having spent 20 years as an NHS consultant as well as an academic," he said, "I know exactly what that looks and feels like."

How many excess deaths?

By Robert Cuffe, BBC News head of statistics

In the three weeks up to Easter, just under 17,000 more deaths were registered than we would normally see at this time of year, a record spike, most of which can be attributed to the epidemic.

But more than half of the coronavirus deaths announced daily have been reported since Easter, so by now the true picture is likely to be far higher.

Registered deaths capture all deaths in the community or care homes and deaths caused indirectly by the virus: people not seeking or getting treatment because our health service is under pressure, or people suffering in the lockdown.

So that gives a better picture of what is really going on. But it takes up to 10 days for deaths to be registered and analysed.

Could most people say they, too, had a sense of the scale of 20,000 lives lost?

That is roughly the population of Newquay in Cornwall and Bellshill in North Lanarkshire. It's the capacity of the Liberty Stadium in Swansea or Fratton Park in Portsmouth. You could visualise those places, if you've seen them.

But while there have been clusters of cases, this comparison obscures the breadth of the virus's impact. Unlike residents of a town or spectators at a sporting ground, the lives lost haven't been concentrated in one particular location. They've been all around.

And if you were to attempt to visualise them, they would not look like a randomly selected cross-section of the population, either. People over 70 are at higher risk. So too are those with underlying health conditions. Data suggest men may be affected more than women, and that there has been a disproportionately large impact on people from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Your perception of the death toll may also differ depending on where you are.

If you live near a main road in London, the UK's coronavirus epicentre, the sound of sirens might have brought home to you the scale of the emergency response. When you look up at the clear spring skies, all but empty of the usual passenger aircraft, your view of the air ambulances carrying patients to hospitals will be unimpeded.

If you live on the Western Isles of Scotland, where the rate of infections has been dramatically lower, the same sensory cues won't be there for you, though you may notice the lack of vapour trails.

The very fact of social distancing makes it harder to commemorate even those you lose who are closest to you. Saying goodbye is often impossible. Numbers at funeral gatherings are strictly limited. You mourn the deaths of loved ones on social media, Zoom and Skype rather than at wakes.

You could compare 20,000 with other death tolls. It's nearly seven times more than the number who lost their lives in the 9/11 attacks and five-and-a-half times more than the number who died as a result of Northern Ireland's Troubles.

But compared with most conflicts and natural disasters, the impact is far more dispersed and hidden. There will be no war cemeteries like those that show the scale of the loss of life in the great conflicts of the 20th Century - though the largest of those, the World War One Tyne Cot Cemetery in Flanders, with its 11,965 graves, would be too small for 20,000 Covid-19 casualties.

Previous pandemics might offer a better, if more ominous yardstick. So far, the toll stands at less than 1/10th of the number of British deaths attributed to Spanish flu after WW1.

But relevant too are the illnesses that kill equivalent numbers each year with minimal attention.

"Twenty thousand deaths represents a huge amount of illness, human pain and personal loss," says Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter. "But it's also important to remember that, although Covid-19 is a far more serious illness than seasonal flu, in each of the winters of 2014-5 and 2017-18 there were over 26,000 deaths associated with flu, which did not receive much attention."

But the most glaring gap in our understanding of the pandemic is the emotional impact of its spread.

Each time a Covid-19 statistic is recorded, how many other people are affected besides? Is it possible to calculate, let alone envisage, the scale of tragedy visited on loved ones, neighbours and friends? Let alone 20,000 times over.

When 82-year-old Ruth Burke became the fourth person in Northern Ireland to die with Covid-19, her daughter Brenda Doherty insisted that Mrs Burke was more than just a number. "I don't want my mum being another statistic," Ms Doherty told BBC Radio Ulster. "She was a loving mother. She was a strong person."

Picture editor: Emma Lynch

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash