The dying teenager who wanted world peace (and love)

- Published

When Californian teenager Jeff Henigson was diagnosed with brain cancer and given two years to live, a children's charity granted him the wish of a lifetime. But Jeff didn't choose to go to Disneyland or meet his favourite footballer - Jeff just wanted world peace.

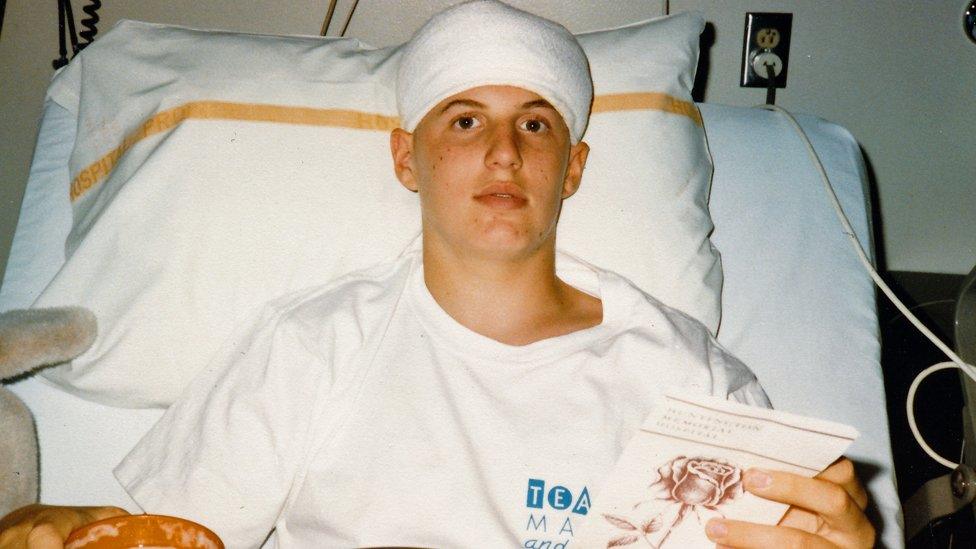

In the summer of 1986, 15-year-old Jeff Henigson was riding his bike to the local electronics shop to buy the last part for a "super laser" he'd been building, when he was hit by a van.

"It's coming in the opposite direction and she doesn't see me and just smashes right into me," Jeff says. "And I'm launched, like a rocket, 10 feet backwards. I land on the back of my head."

Jeff wasn't wearing a helmet, and was knocked unconscious. A few hours later, he woke up in hospital. He seemed to be OK, though, so he was discharged the same day.

But within a few weeks Jeff began having seizures and he returned to the hospital, this time to have a CT scan of his brain.

If it had shown injuries from the cycling accident, Jeff would not have been surprised. But the news was worse than that - the scan revealed a tumour.

"Two things went through my mind," Jeff says. "One was a plan to lose my virginity that summer. And let's just say that did not work out. The second was to complete my laser project."

Jeff was an ambitious teenager, whose dream was to work for Nasa. He believed that the best way to impress them was to build "the most amazing laser" which could bounce a beam off of a reflector that had been left on the moon by Apollo 11.

But the laser was also a way for him to bond with his father, a distant figure, who had served with the US Navy in World War Two.

"I didn't know at the time if that was because of the war or something else. But my father was separate, emotionally, from the rest of us. And I thought, 'Here's this thing we have in common. This fascination with science. This fascination with space.' And that's why I pursued it."

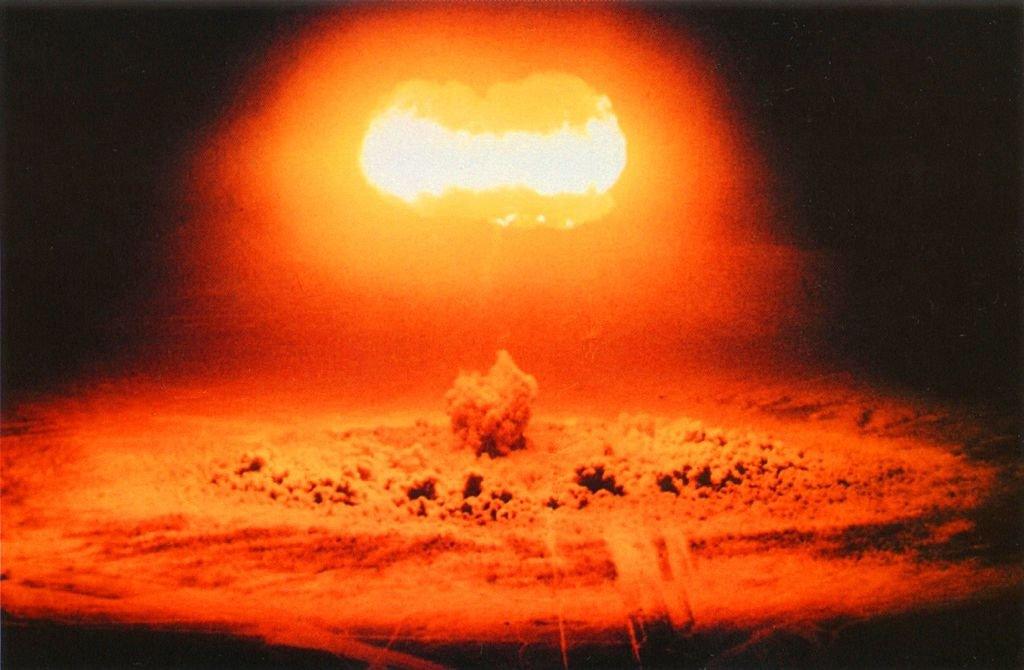

Though Jeff's father never mentioned his experiences in the Pacific when the nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he would talk, at length, about nuclear weapons, the nuclear threat and the US's relationship with the USSR. And this seems to have had an impact on Jeff.

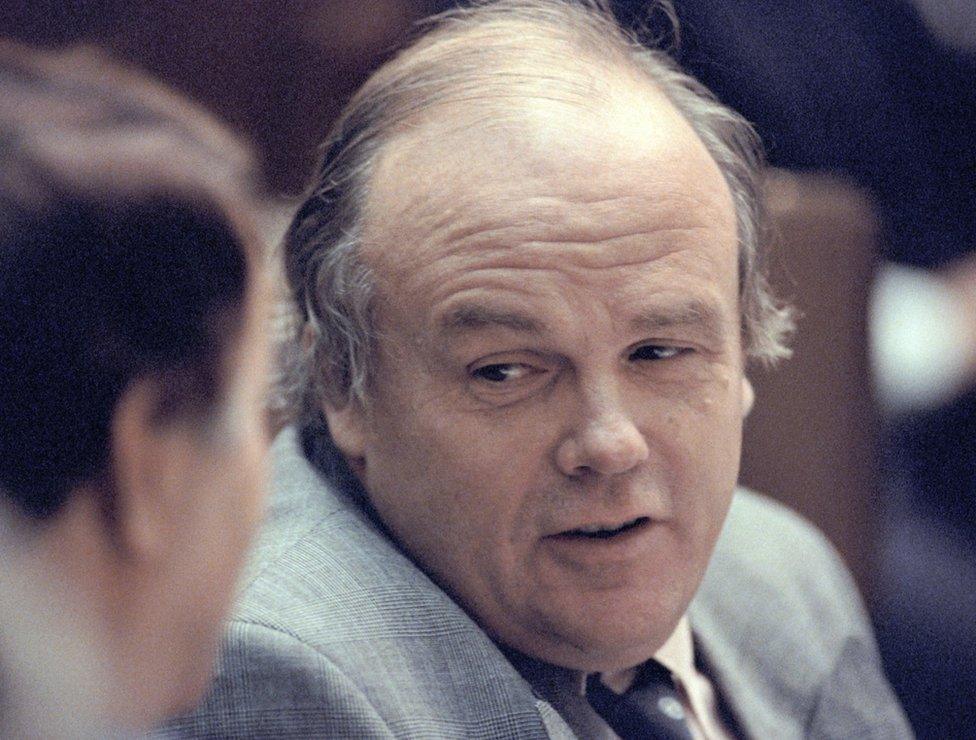

Jeff's father, Bob Henigson

"There was a fictional film in the early 1980s called The Day After. It was about the Soviet Union dropping nuclear bombs on the US. I was probably 11 years old, and I was scared out of my mind. I would often fall asleep at night and go straight into a nightmare about nuclear war," Jeff remembers.

Jeff hoped not only that he would get that dream job with Nasa, but that the organisation would start to work with the USSR rather than competing with it.

"Even when I was fairly young, I could see the potential for collaboration between the US and Soviet Union," he says. "It just never made sense to me that we were pointing nuclear weapons at each other, when we could be collaborating to do extraordinary things in space."

As it happened, Jeff didn't only fail to lose his virginity, he didn't have time to finish his laser either. He needed surgery - quickly. After spending almost six hours on the table, doctors were able to remove the tumour in its entirety. He then faced a seven-day wait to find out whether it was cancerous.

"The doctor walks in, and I could just tell from the look on her face she was not going to deliver good news. She told me, 'I'm very sorry to say you have brain cancer and it's a very aggressive, fast-growing type of cancer,'" Jeff says.

He asked how long he had to live.

"Maybe two years," was the doctor's reply.

Jeff began radiation and chemotherapy treatments and tried his best to keep up with his school work. He also got involved with a support group for teenagers with cancer.

"They'd tell me all about the things they'd done - going to Disneyland or meeting a famous athlete. And I'd say, 'Oh, I thought that wish thing was for little kids,' and they said, 'We're kids.' I just didn't see myself that way."

Helping the teenagers to do these things was an organisation called the Starlight Children's Foundation. Jeff's mum made contact with them on his behalf, and a couple of volunteers, Matt and Teri, came over to his house in South Pasadena to talk about his wishes.

"I said, 'I just have to ask, can you guys possibly get me on the next space shuttle mission?' They just looked at me like 'Oh, you're so ridiculous,' and said, 'Absolutely not.'"

Matt and Teri asked Jeff if he had a second wish, and yes, he did.

He'd recently re-watched The Day After - the film that had given him terrible nightmares about nuclear war a few years earlier - and had visited the library to do more research.

"I was really feeling angry that we were investing so much in nuclear weapons. I thought maybe it would be a good idea to invest in cancer research instead," he says.

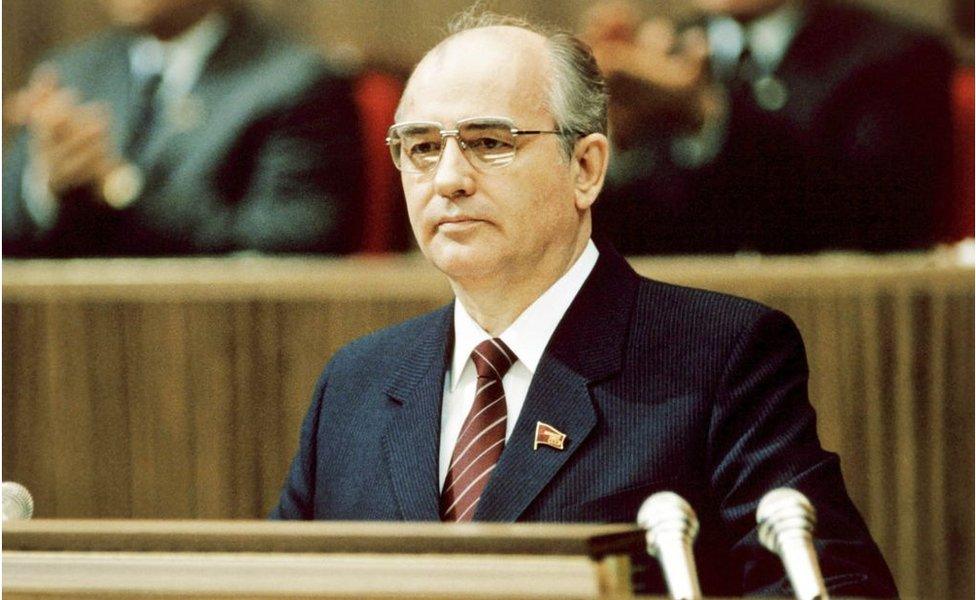

So he told Matt and Teri: "I would like to travel to the Soviet Union and meet with Mikhail Gorbachev, so we can discuss a plan to bring an end to nuclear weapons and the Cold War."

There was a pause.

Matt and Teri then asked Jeff if he had a third wish, probably hoping it would be something easier to satisfy. But he didn't want anything else.

"I said, 'I totally understand if you can't make this happen, but it's my only wish.'"

Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR in 1985

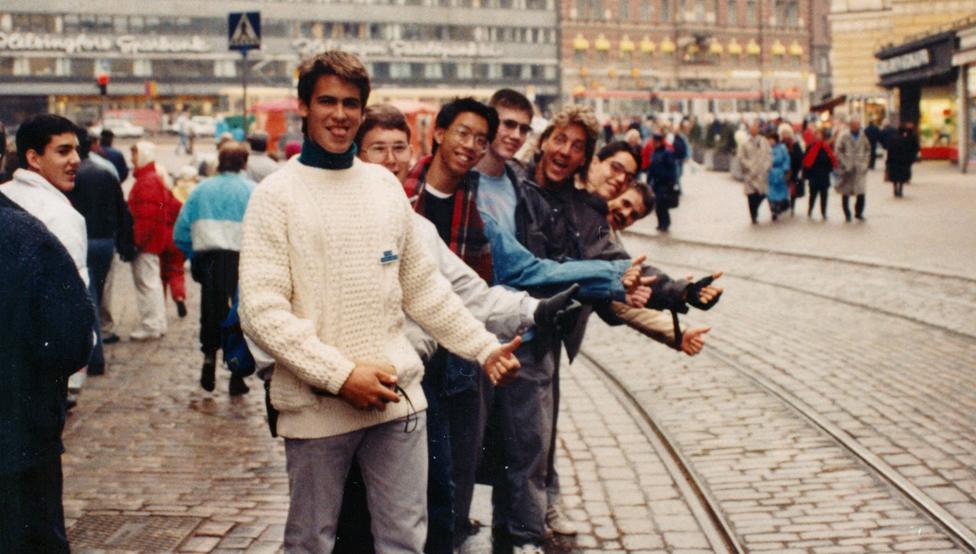

Amazingly, the Starlight Foundation started trying to make it a reality. They arranged for Jeff to join a trip to the Soviet Union with an organisation called Youth Ambassadors of America. Then they started contacting people they thought might have connections to Gorbachev.

They told him that they'd try their best, but couldn't promise that it would happen.

Jeff had an image in his head of what the Soviet Union would be like - thanks in part to films like Red Dawn, released in 1984, in which the US is invaded by the Soviet Union and her allies.

"These films portrayed the Soviets as hardcore militants who were determined to destroy the United States. I must say, I went to see a militant country with a militant people," Jeff admits. "And I was quite surprised by the people I actually met."

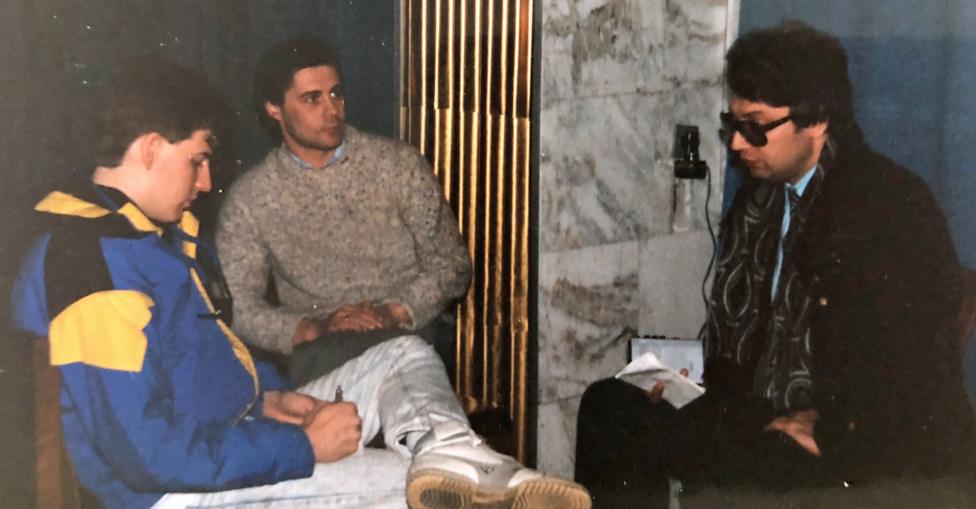

Jeff in Moscow with Youth Ambassadors of America, in April 1988

The Youth Ambassadors were determined to see if they could spot any spies - keeping an eye out for furtive glances and trench coats as they toured the country.

They were disappointed to not find any in Leningrad, but when they were walking through Moscow, a member of the group noticed that they were being followed.

"We were like, 'No way! Are you serious?' And he was like, 'I'm totally sure! Every time I turn around, he turns and looks at whatever's next to him.' It was right out of a movie. And he was wearing a trenchcoat. It was great."

One of the teenagers came up with the idea of counting down from three and spinning around at the same time to say hello in Russian to the man they believed was following them. Jeff was hesitant, he didn't want to risk losing his meeting with Gorbachev.

"But finally I give in. So we do the countdown, and all spin around and yell privyet, and the guy turns around and looks at a wall - there was nothing to look at. It was classic."

In their hotel rooms, they noticed that there were sections of each wall where the wallpaper didn't quite match. One of the Youth Ambassadors decided to poke a hole and found a microphone inside. They were being listened to.

"I guess the only thing that freaked me out was when one of the girls went back to her room and found two guys going through all of her stuff," Jeff says.

"That was a little disturbing. I was wondering if they would go through my things. I had a present for Mr Gorbachev and I didn't want them to steal that. It was my high school yearbook, which everyone in my school had signed. It was a silly little gift, but I liked it and I hoped he would too."

Jeff kept being told that people were working on getting him a meeting with Gorbachev. Then one day he was told to put on the suit that he'd brought for the occasion, and be in the lobby at 8am the next day.

"I wanted to know what his hopes were for bringing an end to nuclear weapons," Jeff says. "But I also wanted to tell him about American kids, what we wanted in this world, and how it wasn't that different from what Soviet kids wanted. We wanted to learn things, travel the world, visit each other's countries. None of these things were facilitated through this militant stance that our countries took towards one another, so I wanted to talk to him about that and see what he had to say."

Soviet participants in the Moscow youth conference

However at the very moment his hopes seemed about to be realised, they were suddenly dashed.

As he waited anxiously in the lobby, a man from Gorbachev's office came to deliver the news that he was unavailable to meet Jeff. When Jeff responded that he'd be free the next day, he was told that Gorbachev would never be available to meet him.

"Who knows what brought an end to that meeting with Gorbachev," Jeff says. "Maybe it was never planned in the first place. I was pretty devastated."

But the man went on to say that they'd arranged an introduction for him to another important figure. Jeff was told to pack an overnight bag, and was driven by limousine to the countryside. He wasn't told anything about the man he was going to meet.

"There was this lovely couple there, and they welcomed me to their home. We ended up having a really lovely experience, and incredible conversations over a fine dinner. They were talking about all sorts of philosophical notions for a better Earth, for how our countries could co-exist," Jeff fondly recalls.

I wasn't until he returned to Moscow and told one of his co-ordinators the name of the family he had had such a wonderful time with that he realised who he'd had dinner with.

"She said, 'You met with Evgeny Velikhov? Do you realise who he is?'"

Mikhail Gorbachev's nuclear adviser and Jeff's host, Evgeny Velikhov

Velikhov was one of the country's top nuclear physicists, she explained, and Gorbachev's right hand man when it came to nuclear weapons.

He hadn't met Gorbachev, but he had spent the evening talking to a man who played a key role in arms negotiations. With the Youth Ambassadors conference over, and his signed yearbook safely delivered to Gorbachev's assistant, Jeff flew back home to California.

His parents met him at the airport, but it wasn't really the welcome reception he'd been expecting. Much to his dismay, neither his mother nor his father asked a single question about his trip. When he raised the subject, it was his father who spoke.

"My dad said, 'I have a question - did you meet with Mikhail Gorbachev?' I said, 'No.' And that was the end of the dialogue. It made me feel like a failure."

Jeff had finished his treatment before the trip, so he now went back to normal life and school.

Then one day, a month and a half later, he received a phone call from Moscow.

"I ran to pick it up and it's Jack Matlock Jr, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. And he says, 'Son, we have thousands and thousands of letters here that are all addressed to you.'"

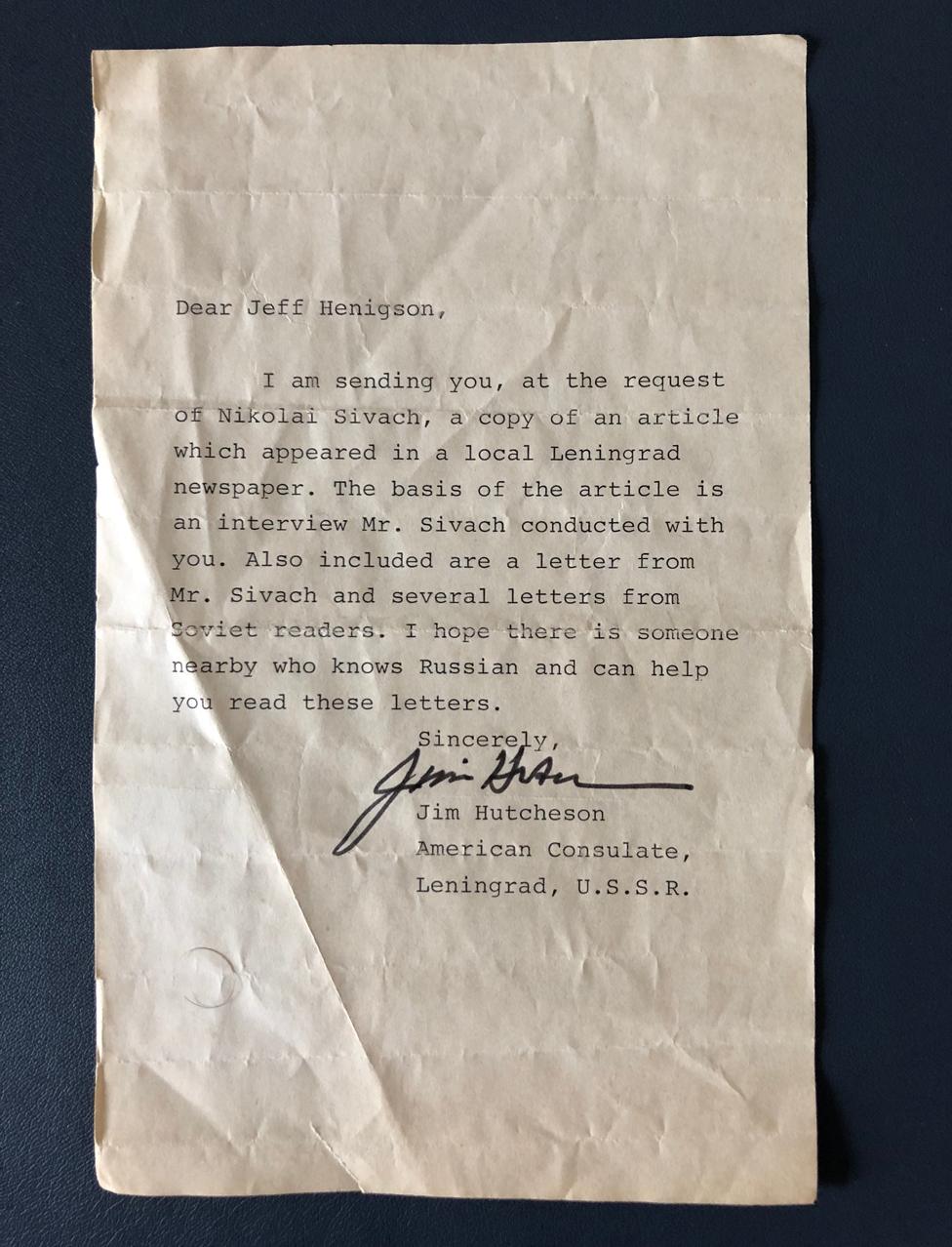

Jeff had spoken to a well-known journalist in Leningrad, who had published a story about Jeff's last wish to visit the Soviet Union. At the end of the piece, he had invited people to write letters to Jeff. And thousands of people from across the Soviet Union had done so.

Jeff being interviewed by journalist Nikolai Sivach

"Mr Matlock said to me, 'Listen, we're not the US Postal Service, we can't send you all of these, but we'll send you a sampling. And son, good luck.'"

Jeff only received a couple of letters in English, but the school's Russian teacher translated the headline of the news story for him - "In leaving, I will stay". A reference to his cancer.

"It made me feel like death was close again and I no longer wanted to be the kid with cancer. So I ended up taking those letters, putting them in a box, and writing 'nostalgia' in block letters on the top."

But despite the grim warning given by the hospital doctor, Jeff's death was not in fact close.

He hid the box away, and kept living his life. Time ticked by, and his tumour didn't return. He moved to London to study at the London School of Economics and then back to the US to attend Columbia University. He started working for the United Nations. Still no tumour.

Then one day in the summer of 2008, when he was 37, Jeff returned to his childhood bedroom with his then-wife.

He was throwing away what he no longer needed or wanted, organising the things he did, and boxing up the laser project that had been interrupted all those years ago. And as he went through everything, he found the box with 'nostalgia' written on the top.

He was at a low point in his life, Jeff says. He had been forced to leave his job at the UN because of seizures caused by scar tissue in his brain. His marriage also was coming to an end. This time, the box held a fascination for him.

"The letters, somewhat overwhelming 20 years before as I wanted to disassociate myself from cancer, were welcome the second time around," he says.

He found a letter in the stack that was written in good English - and there was a phone number. He checked what time it was in St Petersburg and decided to call. The phone rang three times, and a woman answered in Russian.

Jeff asked if, by any chance, her name was Svetlana. And it was. Twenty-three years earlier she had written him a letter in response to the article. She was shocked that he was still alive, and offered to help him translate the remaining letters, and track down others who had taken the time to write too.

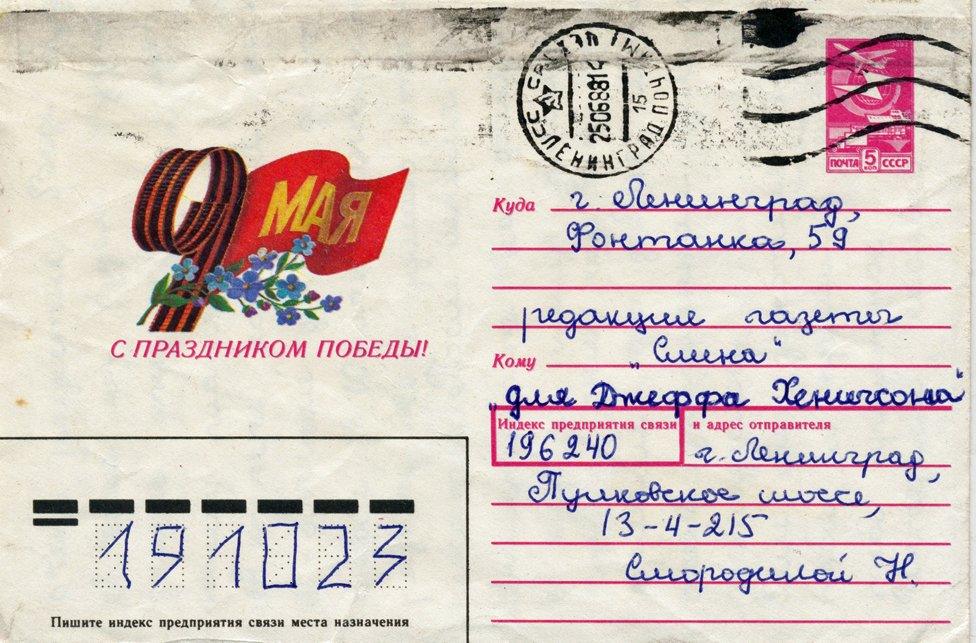

Envelope of letter to Jeff from reader of the article in Smena, June 1988

"A number of volunteers translated the letters for me - one in particular, Eugenia Zhurbinskaya. I knew early on that I wanted to connect with these people. I was interested in documentary film-making, and a couple of film-makers I discussed my story with encouraged me to assemble a film crew, return to Russia, and interview the people who had written to me."

In the Summer of 2011, Jeff got on a plane with a film crew and flew to St Petersburg for 10 days to meet several of the original letter-writers that his contacts had located. He later returned twice more, but no film was ever made.

"Some of the stories were absolutely stunning," Jeff recalls. "There was this woman, Nina Ivanovna Dmitrieva, she was in her 80s then, who had been walking down the street in Leningrad as a child in the 1940s when she hears this rumbling in the sky and a bomb detonates over the building next to her, which collapsed on top of her and crushed her skull. They took her to the hospital, and she goes through three brain surgeries during the siege of Leningrad, and still managed to survive. The area she had the surgery was exactly the same area where I had my tumour. That was mind-blowing. She felt like I was her child."

Nina Ivanovna Dmitrieva, who survived the siege of Leningrad

Jeff fondly recalls a woman called Nelly Slepkova, then in her 80s, who had been a geologist. "She told me that they looked for uranium. When I asked what for, she looked at me like, 'You idiot!' And she said, 'To build nuclear weapons, of course.'"

Nelly Slepkova, geologist

Jeff also had the opportunity to meet the journalist who had written the story about him all those years ago.

Journalist Nikolai Sivach in 2011

"We had a pretty intense interaction. He kept wanting to communicate his success, but unlike every other Russian I'd met on that trip, all the letter writers, he did not talk about his family. I finally asked him about it and he slows down and looks at me and says, 'I had a very difficult relationship with my father.' And there was something I understood there because I hadn't resolved my relationship with my father."

This took a long time. In the Christmas holidays of 2013 Jeff went to visit his parents, and confronted his dad about how emotionally distant he had been. He told him how difficult he had found it being his son.

"When I finished, he thought for a moment and said, 'It is difficult to have lain against me, accusations...' And I just felt this anger building up in me, but he continued, 'identical to those I laid against my own father.'"

For the first time, Jeff's father opened up to his son about his childhood.

His father had been a Hollywood producer, he said, and a gambling addict.

"He'd bring a small fortune home from a well-performing film to his ever-neurotic wife, and then he'd lose it in a late-night card game."

He rarely had anything to say to his children, though they were witnesses to his anger, and he showed little interest in their lives.

"My father repeated the distance, but not the lack of care. He provided for us. He took us on vacation. He came home each night for dinner, even if it was an hour or three later than my friends' suppers with their families. He just couldn't make the emotional connection. He couldn't express feelings," Jeff says.

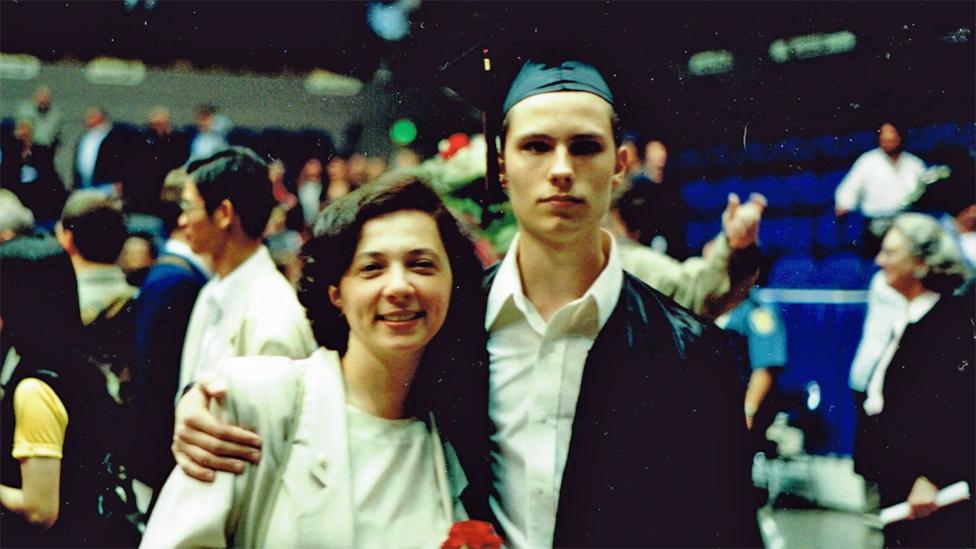

Jeff with his parents, Robert and Phyllis Henigson

"Not long after that, he gathered the family for the first and only time, and told us all that he loved us. He died a month later. So I am absolutely grateful that we found our peace."

Jeff is now 49 and working as a writer. His first book, Warhead, is about his own experiences, and he is following it up with a young adult novel.

A recent MRI scan of his brain has given him a clean bill of health, though he expects to live with epilepsy for the rest of his life.

He's still occasionally in touch with some of the Russian letter-writers, or their English-speaking grandchildren. Nelly, the geologist, is well. Sadly, he hasn't heard for a while from Nina, the survivor of the siege of Leningrad.

Jeff regrets that a trusting relationship between the US and Russia seems very far away, and remains anxious about their vast nuclear stockpiles, and the danger of further nuclear proliferation which he believes "presents a very real and ever-growing threat to human existence".

"Iran seems determined to obtain nukes, and Turkey and Saudi Arabia will not sit idly by if Iran succeeds. The US has withdrawn from one key nuclear disarmament treaty, the INF treaty, and has signalled that another, New START, will not be extended," he says.

"Russia is investing in new nuclear weapons systems and China is on pace to double its nuclear stockpile in the next decade. While I no longer wake up in a cold sweat, I think nuclear war is becoming increasingly likely. There is much to worry about."

All photographs copyright Jeff Henigson unless otherwise stated

Listen to Jeff talking on Outlook, on the BBC World Service (producer Thomas Harding Assinder)

You may also like:

As a gay teenager in post-Soviet Russia, Wes Hurley breathed a sigh of relief when his mother married an American and they moved to the US - but he soon discovered his stepfather, James, was violently homophobic. This led to strained relations, until James underwent an unexpected transformation.