A cluster of islands: How Shetland locked down early and stopped the virus in its tracks

- Published

Early in the Covid-19 outbreak, the Shetland Islands were one of the worst-hit areas of the UK by head of population. Now, no new cases have been detected there for six weeks. Some experts say it offers the rest of the country a route map out of lockdown - but for the first family on the islands to test positive, it hasn't been easy.

It was a clear, bright Tuesday in early March when the plane began its descent. The Shetland archipelago stretched out ahead of the tiny twin-propeller aircraft. Iain Malcolmson looked through his passenger-seat window at the sprawl of islands, aware of how far north he'd just travelled.

Iain, 53, an architect, was on his way home. He and his wife, Suzanne, had spent a long weekend in the Italian city of Naples with four friends. They'd hesitated before setting off on 28 February - news bulletins were full of alarming footage of the Covid-19 cluster in Lombardy, 500 miles to the north of where they were staying.

But official travel advice at that point was clear - it was safe to visit the south of the country - so they'd gone as planned. All the same, Iain recalled spending the trip fastidiously wiping down restaurant tables and washing his hands.

Now, after an overnight stop in Edinburgh, Iain would soon be back at the house in the tiny settlement of Nesting, about 12 miles north of the islands' capital, Lerwick. Locals call this leg of the journey the "white-knuckle express"; in strong winds, the plane has to take off and land at Sumburgh Airport sideways, like a crab. Normally, Iain preferred the 14-hour overnight ferry from Aberdeen. But on this occasion everything seemed calm.

During the first week of March 2020, the novel coronavirus pandemic that had raged out of Wuhan still seemed far away. Here in the tiny aeroplane, Scotland's mainland was 110 miles to the south, Norway was 190 miles to the east. It was still possible to conceive that Shetland might be spared.

"You have to understand what Shetland is like," says Iain. "We're pretty isolated, and I think most people thought it would be something that would happen to other people. It wouldn't have come to Shetland."

Then, two days after he landed, on the evening of Thursday 5 March, Iain noticed he had a headache.

From Sumburgh Head, external in the south to Out Stack, the northernmost point in the British Isles, Shetland has 567 sq miles of land and 1,679 miles of coastline. Of its 100-odd islands, 16 are inhabited, and about half the 23,000 population, like Iain and his family, live close to Lerwick. In the summer, days are up to 19 hours long; in the winter, if you're lucky, you can see the Northern Lights.

The islands were pledged to Scotland by Norway in 1468, and the Norn language - a form of Old Norse spoken on the islands - died out in the mid-19th Century. The Scandinavian influence is still strong, from the Nordic-derived placenames - Burravoe, Grutness, Mavis Grind - to the brightly coloured timber-clad houses dotted across the landscape, and the annual Up Helly Aa fire festivals, which conclude with the torching of a Viking galley.

Scalloway, Shetland

But despite this Shetlanders don't want the rest of Scotland to forget about them. A 2018 law introduced by the islands' Member of the Scottish Parliament banned public bodies from producing maps that depict Shetland, for reasons of cartographical convenience, in a box in the Moray Firth or east of Orkney rather than its true geographical location.

Iain was raised as a Shetlander. He left to study architecture in Edinburgh, where he met Suzanne, but two decades later, after starting a family, they decided to open a practice back on Shetland. It had been their dream for a long time.

"It's just the freedom that you have," he says. "You've got family, friends and that sort of thing. It's a very friendly, positive sort of place." He's a well-known figure in Shetland - he sits on the local community council, is a keen Up Helly Aa participant and has played guitar in local bands. The property he and Suzanne designed for their family to the dimensions of a Norse longhouse was featured on the BBC's Scotland's Home of the Year programme.

The Malcomson family home in Nesting, Shetland

Shetland might be remote, but it is no backwater.

Thanks in part to the discovery of North Sea oil in the late 20th Century, its per capita GDP is among the highest of all Scotland's local authority areas. In the 1970s, the local council drove an extraordinarily hard bargain with the energy companies who wanted to operate the terminal at Sullum Voe. Compensation payments were invested in a charitable trust that ensures the islands have exceptionally good public services. "The facilities up here are second to none," says Iain. "Every little community has its own leisure centre or pool."

When he woke on the morning of Friday 6 March, Iain still didn't feel well. For the past two days he'd gone in to work, but now he clearly wasn't up to it. One of the friends he'd travelled to Naples with, a Glasgow resident, wasn't feeling great either and had been advised by the NHS to get tested; so Iain and Suzanne arranged to be tested too.

Nurses arrived at the couple's house. They stripped off on the porch and, before stepping inside, changed into full PPE - visors, protective suits - before taking swabs from the Malcomsons' noses and the backs of their throats.

"It was like something off the telly," Iain says. The whole scenario was unnerving, but the staff were reassuring. "They were saying: 'You'll be fine, the chances of you having it where you've been are almost zero. So don't worry about it.'" He says he and Suzanne stayed indoors that weekend anyway.

There was a delay while the samples were tested - Iain was told they had to be flown down to Aberdeen and then taken to Glasgow. On Sunday evening the results came through: Shetland had its first confirmed cases of Covid-19.

"Everybody was gobsmacked," says Iain. "And it all kicked off from there."

At least one person on Shetland wasn't surprised by the arrival of the virus. His name is Michael Dickson.

Not long before, as NHS Shetland's chief executive, he'd been summoned to the mainland for a presentation on the likely impact of the pandemic. "I can honestly say when I came out of the government briefing, it was without a doubt the worst day of my entire career," he says. "To go back to Shetland and have to share that with the people of Shetland was incredibly difficult."

Gilbert Bain hospital, Lerwick

He also knew that Shetland's geographical isolation would make treating the virus there especially challenging. "Lovely as it is," he says, Lerwick's Gilbert Bain Hospital "was never built for this." There is no intensive care unit anywhere on the islands. At that stage, any patients who became critically unwell would need to be flown to Aberdeen or elsewhere on the mainland in an enormous RAF Atlas military transport aircraft.

But Shetland would have advantages, too. Standing at his front door, "I can cast my eye out and see no-one", he says. "There's houses but I'm not going to see anyone walking down the street. If I go for a five-mile run I might run into three or four people. It's just a completely different place to socially distance."

Also, an outbreak of measles on the Aberdeen ferry meant NHS Shetland had very recent experience of carrying out contact tracing. "That was hugely useful," he says. "The fact is, knowing the geography of Shetland, the different communities, makes a huge difference."

This was crucial, Dickson says, after the first positive test results came in. "When that call went out from the Public Health teams to say we need to do this now, there wasn't a debate. People came in on their Sundays and said 'Right, let's start, let's get on with this.'"

The nurses in visors and PPE suits who came to test the Malcolmsons took the names of everyone they had come in contact with and tested them too.

According to Dr Susan Laidlaw, NHS Shetland's public health consultant, staff from other NHS departments were drafted in to phone contacts. "We had a week of very long hours and intense work following up the contacts, identifying new cases and getting them tested and isolated," she says. "Although difficult at the time, this did help to contain the initial outbreak."

"Everybody at our work got it," Iain says. "And everyone from our work's family ended up getting it." Some had diarrhoea, others lost all sense of smell and taste. Others fared worse - Iain says the father of one of his employees had to be airlifted to Aberdeen. He would later make a full recovery.

While the contact tracers scrambled to identify how far the virus had spread, Iain's condition was getting worse. Suzanne's symptoms were cold-like, but his were more like the flu - a high temperature, shivering. There was talk of flying Iain, too, to Aberdeen. The prospect terrified him. "I really didn't want to go off the island," he says.

After a few days, Iain's symptoms began to improve. But the knowledge he might have given the virus to others in less robust health weighed heavily on him. He was terrified he'd given it to his parents, both in their 80s. "That stress was there, knowing that you could have given it to people who weren't going to be as lucky as you."

And while he'd been feeling unwell, Iain hadn't felt much like looking at social media. He hadn't yet seen the rumours about him.

The virus spread quickly on Shetland. On 12 March, four days after Iain and Suzanne's test results came back, the number of confirmed cases announced in the local press rose from two to six; five days later, they stood at 15; by 19 March, they had risen again to 24.

These were not enormous numbers, but they were enough to ensure that Shetland had the highest number of Covid-19 patients in Scotland relative to its population, and one of the highest in the UK. "I think we were top of the graph possibly in the world at one point," says Dickson.

As Dickson sees it, this early spike was, in part, testament to the efficiency of the contact tracing teams. A dedicated Covid ward had already been set aside at the hospital. But compared to Orkney and the Western Isles, which had largely been unaffected at that point, Shetland stood out - and Shetlanders were understandably anxious.

Dickson believes this was a crucial factor in containing the outbreak; it meant islanders were already taking social distancing seriously before controls on movements were enforced.

"It's a difficult thing to say, but I think having those cases early on enabled us to move possibly more quickly than had we not had cases until later on in the pandemic," he says.

"My family live down in Brighton and if you went down to the beach there a week before the lockdown occurred you wouldn't have known anything was different. In Shetland, things have been different pretty much from day one."

As early as 11 and 12 March, two Up Helly Aa fire festivals - hugely important events in Shetland's social calendar - were called off, in response to appeals from the health board. The following day, while the Cheltenham Gold Cup was going ahead as planned 700 miles away, it was announced that nearly all Shetland's schools would close from 16 March - a week before the rest of the country.

Cafes, bars, restaurants and leisure centres were already shutting down across the islands long before the Scottish and Westminster government imposed their lockdowns, says Maggie Sandison, chief executive of the Shetland Islands Council.

"I think there's a really strong sense of community in Shetland," says Sandison. Naturally, islanders were anxious to do the right thing by their neighbours. But also, because such a high proportion of the population knew each other, "people were aware that they may have come into contact with somebody who then became a positive case" - and this in turn meant they knew to self-isolate.

Sandison says the early decision to close schools was taken in part because some teachers had been part of the contact tracing teams and were advised to stay home after coming into face-to-face contact with people who had tested positive. On a sparsely populated group of islands, this was enough to put a strain on staffing levels. At the same time, "there was quite heightened anxiety from parents" some of whom were keeping their children at home already.

Ferry operators also began preventing tourists and non-residents from travelling to the islands before nationwide restrictions were brought in. "Because the transport links with the mainland were reduced early on, and the transport operators are only taking people who have essential reasons for travel, this has to some extent isolated the islands," says Laidlaw.

A weekly Covid-19 Facebook livestream hosted by Dickson would attract as many as 600 viewers at a time. And Shetland's community spirit wasn't just about locking down and staying vigilant.

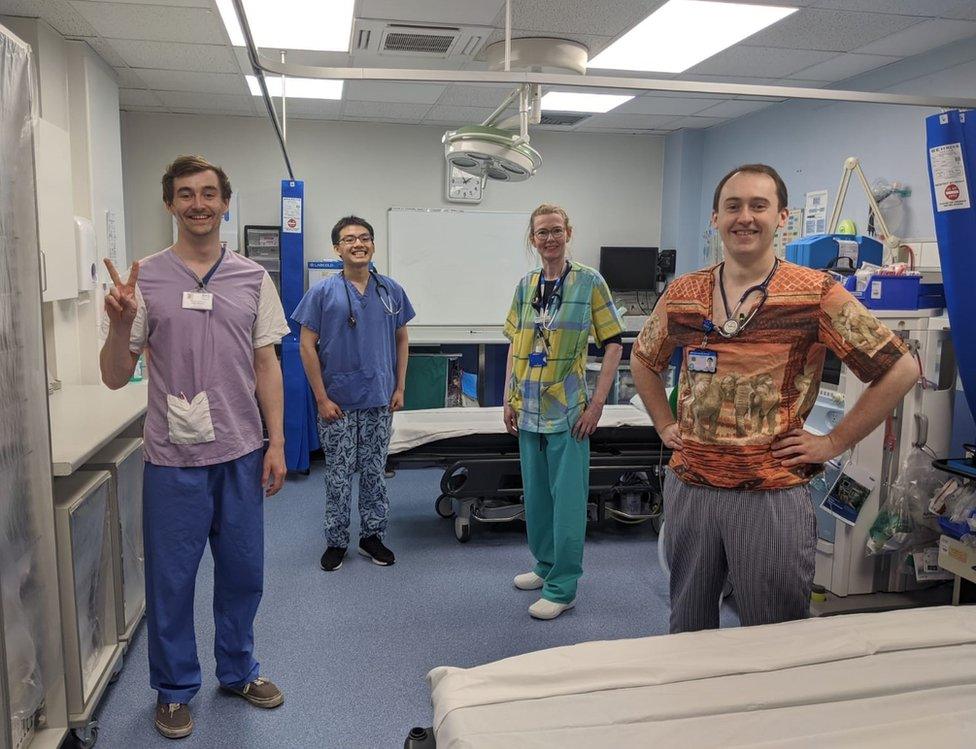

When laundry staff at the hospital found they had a shortage of scrubs, a sewing pattern was posted on Facebook along with an appeal to turn any unwanted bedsheets into medical clothing. "We had bags and bags of finished scrubs within days," says a personal assistant working for NHS Shetland, 38-year-old Lisa Grey, who oversaw the Shetland Scrubs project.

NHS Shetland staff in colourful scrubs made by volunteers

As well as bringing extra colour to the wards, superhero patterns on erstwhile children's duvet covers proved especially popular with medical staff.

"You can see it when you're flicking through Facebook - folk saying, 'If anyone needs shopping, I'm off tomorrow.' If anyone needs help, there will always be someone that'll help," Grey says.

With the rest of Scotland and the UK soon following Shetland's example in locking down, and many other Covid-19 clusters emerging around the UK, the islands felt less like an outlier. But as March turned to April the archipelago's cases kept rising, and before long it would report its first death.

Word had spread quickly around the islands that the Malcolmsons had been the first to test positive; Iain had never expected otherwise. "One thing about Shetland is you have absolutely no anonymity," he says. "People know you're the person that's brought it in."

To Iain, it was understandable, in a perverse way, when rumours about his family began to circulate on social media. Their names hadn't been officially released, and "in the absence of fact, people just make stuff up", he says. "That's never going to change. There's always a few idiots out there." As he hadn't been looking at Facebook, it was news to him when friends got in touch to say the family was "getting a serious amount of flak".

According to the gossip, on the weekend he and his wife had been tested, "we were everywhere - we were out on pub crawls, we were out at concerts," says Iain. "That weekend we did everything in Shetland that everyone else was doing. And I don't know why, but they were totally convinced that they'd seen us there."

It was bad enough when it was confined to Facebook. Then tabloid journalists began calling the house. Iain's friends and family were feeling the pressure. They urged him to go on Facebook and correct the record.

Iain really didn't want to do it. He wasn't a big social media person. What if it backfired? Might this not antagonise people further?

But something needed to be said. Late one evening, Iain sat down at his computer and began typing.

RISK AT WORK: How exposed is your job?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

COMPARING COUNTRIES: The pitfalls of doing so

R0, FURLOUGH: The language of the outbreak

RECOVERY: How long does it take to get better?

"After some of the hardest few days we have ever experienced, and it is only getting harder, it is with a heavy heart that Suzanne and I feel it is necessary to put straight some of the more vicious rumours that are circulating about us on social media in Shetland," he wrote. After being told they were to be tested and advised to self-isolate, "we have not left the house since and have not been out partying, or socialising of any kind".

The response was overwhelmingly positive. The post was shared over 1,000 times; friends and neighbours backed up their account; the record was duly corrected. Iain didn't bear a grudge - this was what happened in the absence of reliable information. "It showed you the good side and the bad side of social media."

According to National Records of Scotland (NRS), the first death of a person in Shetland with Covid-19 took place some time between 30 March and 5 April. Five more came the following week; a sixth the week after that. On 6 May, another death was announced; there have been no more since then. Tragically, five of the seven were in a single care home.

Shetland has good reason to hope it has seen its last coronavirus death of the current peak. The last time a resident of the islands tested positive was 20 April - since then, the total number of confirmed cases has stood still at 54. Nine days afterwards, Dickson told Shetland's local media that the outbreak there may have "plateaued".

"They've obviously managed to control the virus by doing an early lockdown," says Hugh Pennington, emeritus professor of bacteriology at the University of Aberdeen, who has advised the Scottish and UK governments. "Full marks to them, really. Whatever they did worked."

Shetland's isolation and lack of new cases makes it, along with Orkney, effectively "a very small-scale New Zealand", says Prof Pennington - and like New Zealand, he says, the islands could in theory lift their lockdowns by strictly controlling who comes and goes.

But the islands' authorities are cool on the idea of a New Zealand-style quarantine. Dickson notes how many patients have to travel to Aberdeen for routine, non-Covid medical treatment: "So are we saying those people aren't able to go to the mainland because we've closed our borders?" It's also necessary for the fishing and oil industries for some people to have the ability to travel in and out.

Lynn Johnson says her business depends on tourism

It's not just winter and spring events like the Up Helly Aa festivals that have been postponed though, as a result of the lockdown. In 2020 the long summer days will pass on the islands without sheepdog trials, the accordion and fiddle festival, Shetland Wool Week. And there's no end in sight - the first fire festival of 2021 has already been cancelled.

The absence of tourists is also being keenly felt.

"My business wouldn't exist without tourism," says Lynn Johnson, who runs the Cake Fridge tea room on a single-track road between Voe and Aith on West Shetland Mainland's northern coast.

To keep it going, she needs both the lockdown to be lifted and travel to resume. "We really, really need that spring, summer, along with the big tourism boost that our islands get, to see us through the winter. And we're not going to have that at all."

But for now, the lockdown is holding.

Shetland is ready to resume contact tracing - which was halted in late March, as in the rest of the UK - and Laidlaw says the islands are well prepared for the next phase. Since late April, Shetland has had its own Covid-19 testing equipment, meaning samples no longer have to be sent to the mainland. And two small planes - like the one Iain flew back from holiday on - have been converted into air ambulances.

In spite of the apparent success of Shetland's track-and-trace operation, no-one may ever know how the virus arrived there. Iain and his wife may have been the first people on Shetland to have tested positive, but that doesn't mean they were the first to bring it.

"Obviously I know about the contact tracing, the Malcomsons and their experience," says Dickson. "We picked up those people who were diagnosed and got a positive result. I always say, those are the ones we know about. Shetland is a small community but we do have people who come in and out of the islands frequently."

The couple most likely travelled in with the virus, but "what we can't guarantee is they were the only people". And there is no guarantee the Malcolmsons caught the virus in Italy either, as it is thought to have been circulating in Edinburgh, where they changed flights, since February.

Iain knows better than most the importance of social distancing. And he knows he's fortunate to being doing so in Shetland, where keeping apart from others is easier.

"It's absolutely beautiful," he says. "You feel like you're on holiday. You have to be pretty disciplined about actually working. But this could be our summer, so you have to make hay while the sun shines."

Follow @mrjonkelly, external on Twitter