Dalai Lama: Seven billion people 'need a sense of oneness'

- Published

The leader of Tibetan Buddhism sees reasons for optimism even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. People are helping one another, he tells the BBC's Justin Rowlatt, and if seven billion people on Earth develop "a sense of oneness" they may yet unite to solve the problem of climate change.

The first time I met the Dalai Lama he tweaked my cheek.

It is pretty unusual to have your cheek tweaked by anyone, let alone by a man regarded as a living god by many of his followers.

But the Dalai Lama is a playful man who likes to tease his interviewers.

Now, of course, such a gesture would be unthinkable - our latest encounter comes via the sterile interface of a video conferencing app.

The Dalai Lama appears promptly and sits in front of the camera, smiling and adjusting his burgundy robes.

"Half-five," he says with a grin. His eyes sparkle: "Too early!"

We both laugh. He is teasing me again.

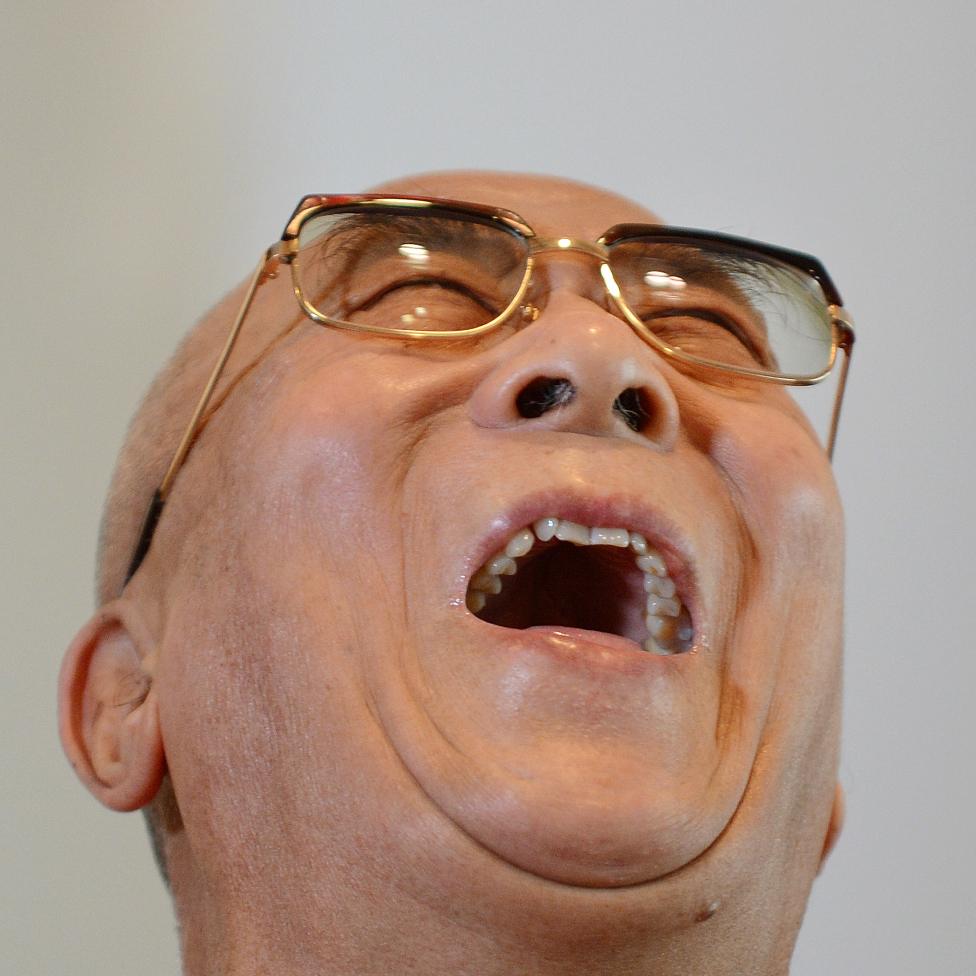

The Dalai Lama speaks of the importance of compassion in a video call with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt

I had been delighted when the leader of Tibetan Buddhism had agreed to an interview but a little downcast when his secretary told me it would be at 09:00 Indian Time.

That's 04:30 UK time. It would mean getting into the office at 03:30.

James Bryant, who produced the interview, took the matter in hand.

"Although nothing is impossible for us, that would be exceptional," he wrote.

His Holiness's secretary graciously agreed to move it to 10:00 Indian time.

So, at 05:00 on Wednesday last week I found myself in a BBC office in London watching a video feed from Dharamshala in northern India.

The contrast could hardly have been greater.

I sit among rows of empty desks in the grey half-light while in a palace atop a mountain redoubt in the foothills of the Himalayas, monks in saffron and purple robes sweep by, tweaking cables and adjusting cameras in a gilded room.

Clear mountain light streams in through the windows.

There are worse places to endure lockdown than a palace with sweeping views of icy mountain peaks, and the Dalai Lama acknowledges as much.

The Dalai Lama's home in exile, McLeod Ganj, near Dharamsala

"Here we have very pure fresh water and fresh air. I stay here peacefully," he tells me with another of his signature explosive laughs.

His thoughts are with those who are suffering and afraid during this terrible pandemic but he says there has been much to inspire and to celebrate.

"Many people don't care about their own safety but are helping, it is wonderful."

The Dalai Lama smiles.

"When we face some tragic situation, it reveals the deeper human values of compassion," he continues. "Usually people don't think about these deeper human values, but when they see their human brothers and sisters suffering the response comes automatically."

I ask what advice he has for people who are anxious or frightened.

The important thing is to try not to worry too much, he suggests.

A monk wearing a mask in McLeod Ganj

"If there is a way to overcome your situation then make effort, no need to worry," he explains.

"If truly there is no way to overcome then it is no use to worry, you can't do anything. You have to accept it, like old age."

The Dalai Lama will be 85 in a few weeks.

"It is no use me thinking I am too old, no use as an old person," he continues.

"Young people are physical, their minds are fresh, they can make a contribution for a better world but they are too much excited." He chuckles.

"Older people have more experience they can help by teaching the young. We can tell them to be calm," he says with another explosive laugh.

He believes the young will be at the forefront of tackling what is now one of his most pressing concerns: the need to tackle environmental challenges.

He says he has seen the effects of climate change in his own lifetime. He seems quite emotional as he remembers his youth.

The 14th Dalai Lama was born in a remote village on the high plains of Tibet in 1935.

He was identified as the tulku, the reincarnation, of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1937.

"When I was in Tibet," he tells me, "I had no knowledge about the environment. We took it for granted. We could drink water from any of the streams."

It was only when he arrived in India and later began to travel the world that he realised just how much damage was being done.

"I came here to Dharamshala in 1960. That winter lots of snow, then each year less and less and less.

"We must take very seriously global warming," says the leader of Tibetan Buddhism.

A light dusting of snow in the Himalayan foothills above McLeod Ganj (January 2017)

He urges the world to invest more in wind and solar energy and to move away from dependence on fossil fuels.

The important thing, he tells me, is for us to recognise that we are not individuals alone, we depend on the community we are a part of.

"No matter how rich your family is, without the community you cannot survive," he says.

"In the past there was too much emphasis on my continent, my nation, my religion. Now that thinking is out of date. Now we really need a sense of oneness of seven billion human beings."

This, he says, could be one of the positive things to come out of the coronavirus crisis.

But while the world woke up quickly to the threat from this virus, global warming is a more insidious threat, he points out, coming "decade by decade".

This may make it seem less urgent, and he worries that soon we may find it is beyond our control.

The challenge ties in to another of the Dalai Lama's great preoccupations: education.

"The whole world should pay more attention to how to transform our emotions," he tells me.

"It should be part of education not religion. Education about peace of mind and how to develop peace of mind. That is very important."

Now comes the most difficult part of the interview. I want to discuss the Dalai Lama's own death - or more accurately, the question of his rebirth.

This is not just an issue for him. What happens when he dies will be key for the future of Tibetan Buddhism and of the Tibetan freedom movement.

China sent troops into Tibet in 1950 to enforce its claim on the region.

Many Tibetans fiercely oppose what they see as an illegal occupation.

As the spiritual leader of the Tibetan people, the Dalai Lama has been the figurehead for this opposition.

He reminds me that he has said before that his death may well mark the end of the great tradition of Dalai Lamas - the words mean "great leader" in Tibetan.

"It may end with this great Lama," he tells me, laughing and pointing to his chest.

He says the Himalayan Buddhists of Tibet and Mongolia will decide what happens next.

They will determine whether the 14th Dalai Lama has been reincarnated in another tulku.

It could be a fraught process. The boy who the current Dalai Lama identified as the reincarnation of the second most powerful figure in Tibetan Buddhism, the Panchen Lama, was abducted in 1995. It is the Panchen Lama who would normally lead the search for the reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama.

The Dalai Lama says what his followers decide is not an issue for him.

"I myself have no interest," he says, laughing.

His hope is that when his last day comes he will still have his good name and can feel that he has made a contribution to humanity.

"Then finish," he says with another laugh.

And with that, our interview is over.

You may also be interested in:

Video of Japanese Buddhist DJ Gyosen Asakura's techno service went viral on social media.