'After mum died, no-one talked about her for 15 years'

- Published

Iain Cunningham always believed that his birth had something to do with his mother's death, but whatever it was seemed to be a family secret that couldn't be discussed. It wasn't until Iain was an adult with a family of his own that he uncovered who his mother really was and why she had died.

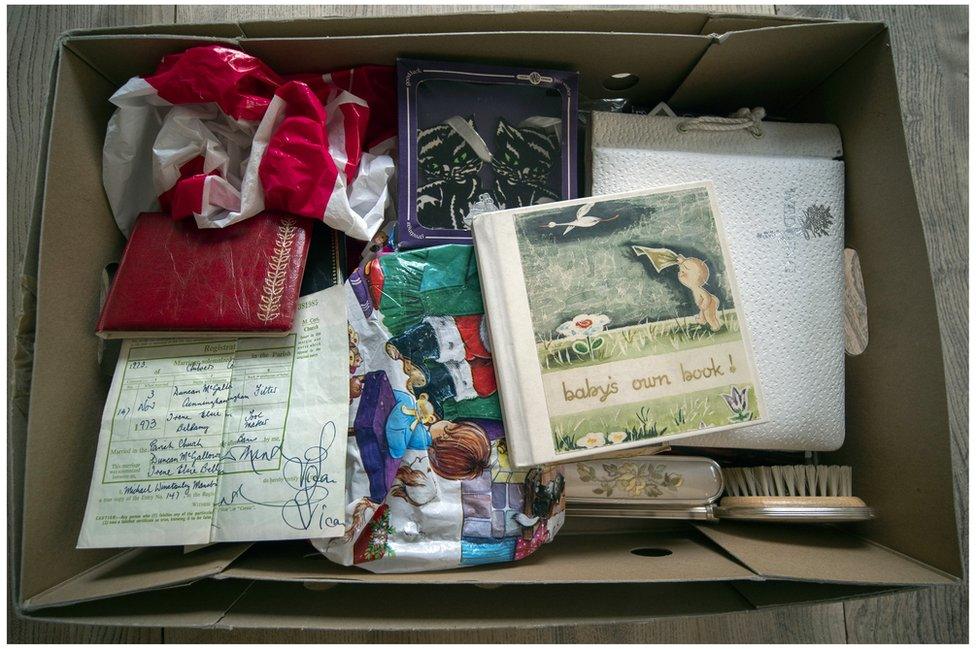

The feeling of opening the box on his 18th birthday is one that Iain Cunningham will never forget.

"It was like a religious experience," Iain says. "It was very powerful - it was the first time I'd seen photographs of her, the first time I'd seen anything."

The box had been gathering dust in the attic for 15 years, ever since the woman whose belongings had been carefully packed away inside it had died - Iain's mum, Irene.

There were photos from Irene's wedding day in the early 1970s and a plastic bride-and-groom figurine that had decorated the top of the wedding cake. There was a wooden music box, underneath whose lid a ballerina in a net skirt twirled above satin-lined compartments where Irene would tuck away her jewellery. And there was a vanity set that once sat on Irene's dressing table, with hair from her head still entwined in the bristles of the brushes.

Iain found his baby book in the box too, inside which his mother had begun to document her firstborn's new life. She'd written his date of birth and the colour of his eyes - but most of the book was empty.

"It felt to me like the pages of an untold story," Iain says. "I needed to fill in that blank space."

Don, Iain's father, was 18 when he first met Irene, at a dance at Coventry's Locarno ballroom.

"And then we arranged to meet the next week under the bus station clock," Don says.

The couple went to the pictures and from then on met regularly. Don had a job at Dunlop in Coventry making aircraft brakes, while Irene, who was a year older, worked at a textiles factory in Nuneaton sewing the flies into trousers. She and the other girls would sometimes smuggle in their own material to make clothes for themselves on the sly. Later she moved on to work for a hosiery manufacturer in Hinckley called Flude's, pulling tights on to a Perspex leg and straightening them out before they continued down the production belt.

"We didn't have two ha'pennies to rub together," Don remembers. "Inflation had gone through the roof so we didn't go out an awful lot, but there was a pub not far away that we used to walk to, and we'd sit with one drink all night long because we were saving to get married."

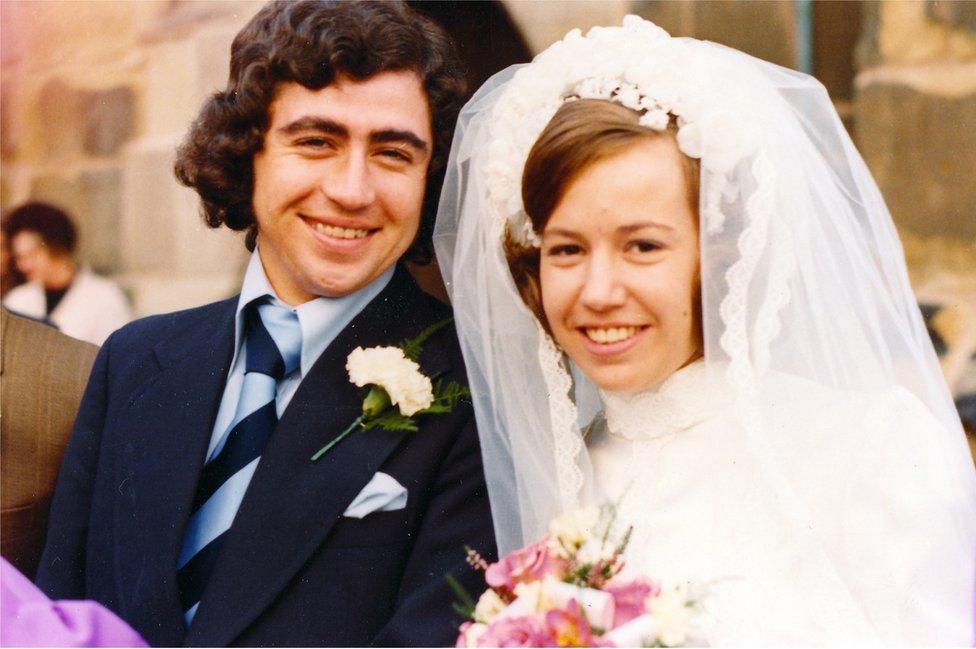

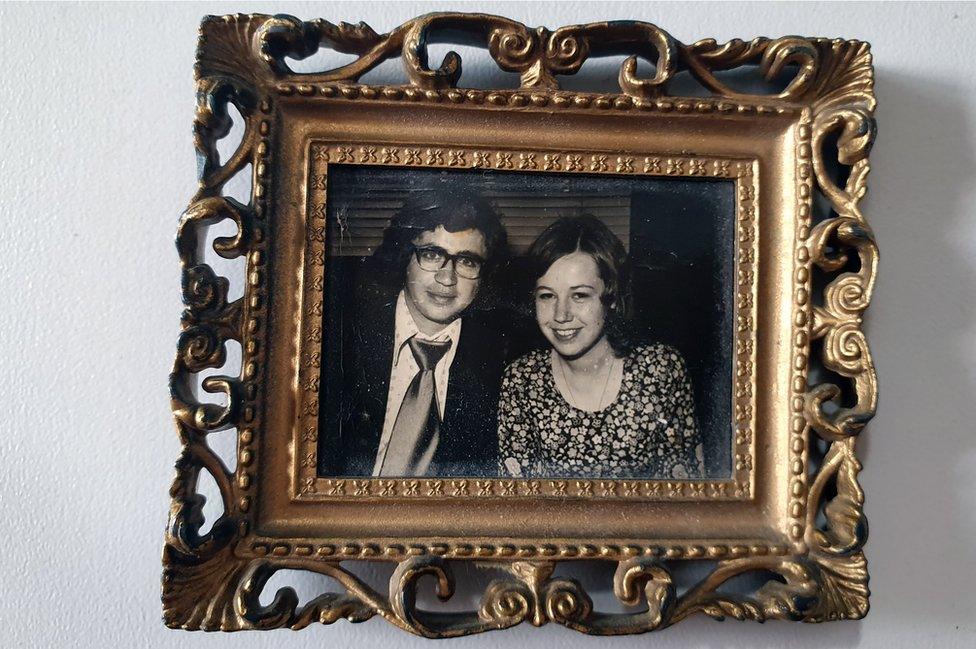

Don and Irene married in early November 1973

Don and Irene tied the knot a couple of years later - just as the UK economy was grinding to a standstill - and within a couple more years they were expecting their first child.

"Irene was very happy when she was pregnant," Don says. "We were both very happy."

But soon after Iain was born, in January 1976, things started to go wrong. Irene confided in her best friend that she'd been hallucinating while she was recovering from the birth in hospital, and when she brought her baby son home she couldn't sleep, began writing strange notes, and told her mother, "I'm not Irene, you know, I'm Irene's ghost."

Don took Irene to the doctor who diagnosed postnatal depression. Irene was sectioned and admitted to the psychiatric unit at the local hospital where she was sedated and underwent electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

"And not long after that she went into that catatonic stupor," Don says.

For a period Irene was unresponsive and immobile, almost as though she was in a coma. When she came round her personality had changed - she was paranoid, withdrawn and would stare into space, but would sit up in bed from time to time and eat a packet of biscuits.

"I was devastated," Don says. "But I had Iain to look after, work to go to and Irene to see in the evenings - I just had to keep going."

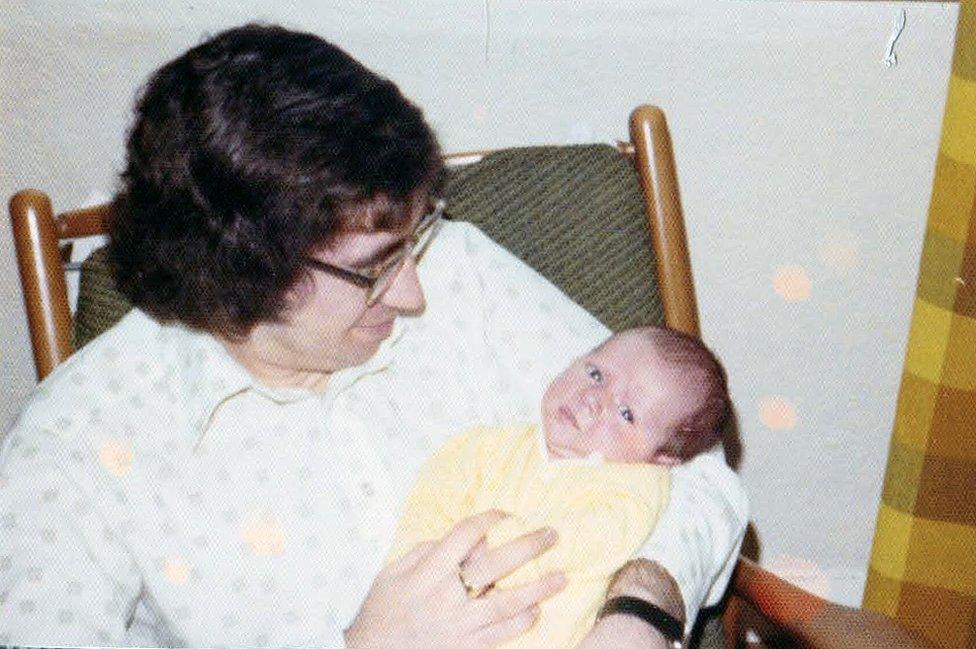

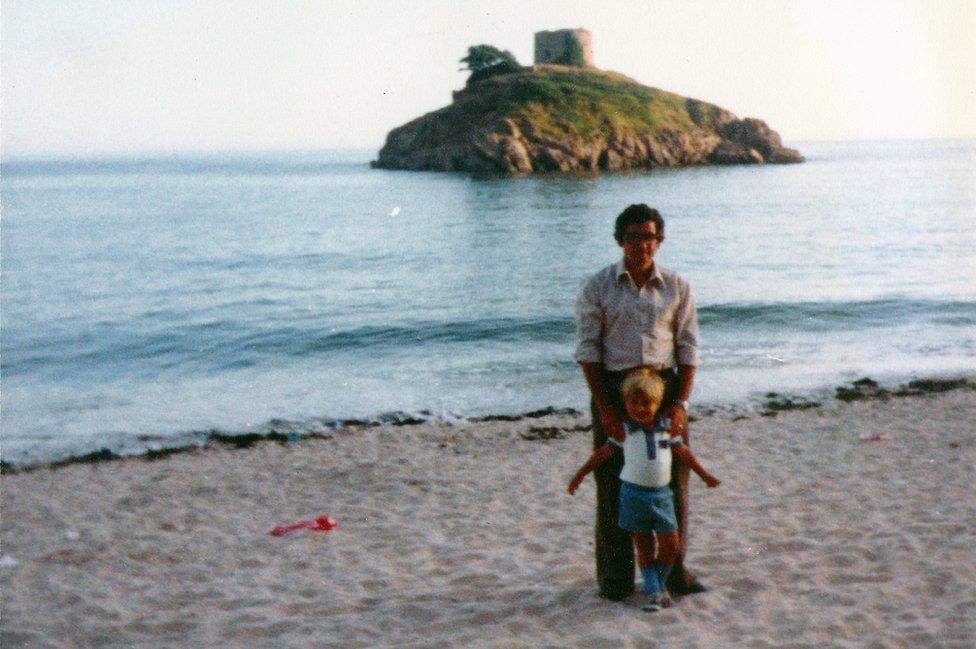

Don holding his newborn son, Iain

Family and neighbours rallied round to help with the new baby while Irene was in hospital - a period throughout which Don recalls feeling "completely in the dark" about what was going on with his wife's health and the treatment she was receiving.

"It was a different world - doctors didn't give you any information and you weren't told what medication they were on or for what," he says. "It was never explained to me what a catatonic stupor was and in those days there was no internet where you could go and look things up. My life consisted of going to the hospital every night and just sitting next to someone who was completely uncommunicative."

Irene spent about nine months in hospital, but there then followed a period of around 18 months during which she was living happily at home with her young son and husband, taking Iain to the park and to cafes, and on walks to visit friends.

But at a certain point Irene started becoming manic. She couldn't stop talking, day and night, wasn't sleeping, and soon had to be readmitted to hospital.

"I just didn't understand why it could happen again when she seemed so happy to be with Iain," Don says.

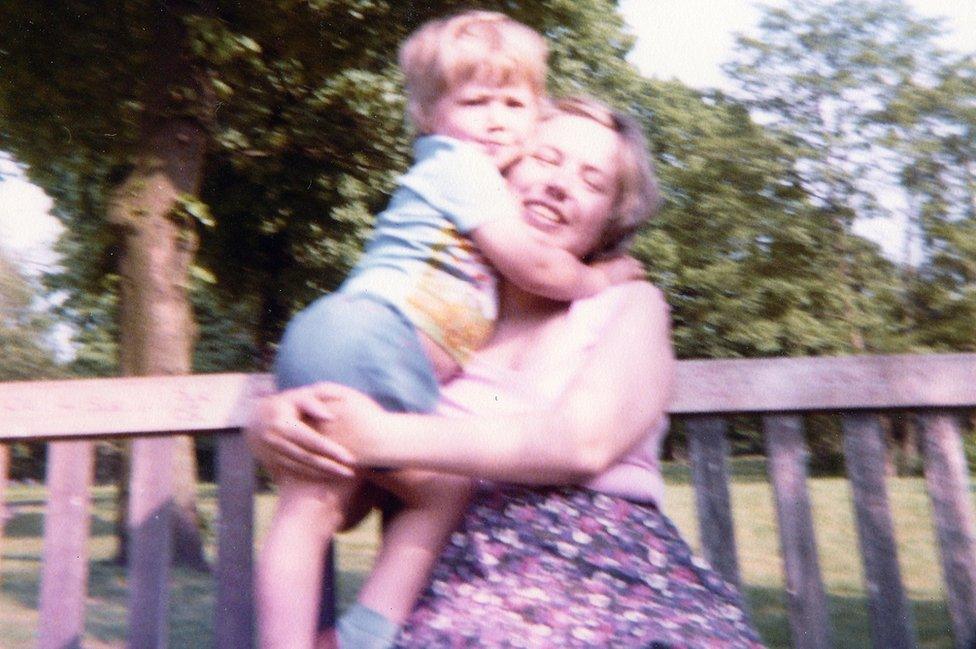

Irene with Iain (aged two-and-a-half)

One late October morning about three months later, the phone rang as Don was working in an upstairs office at the Dunlop factory. It was Tom, Don's brother. There was terrible news. Irene was dead.

At the hospital Don was asked to identify his wife's body. They told him she had died of heart failure, but very little else - he wasn't given a proper explanation of what had happened or why.

"I was 28 and my life had fallen apart," Don says. "I didn't know what I was going to do with myself, left on my own with a very small child. How was I ever going to get my life back together?"

Don and Iain (aged three-and-a-half) on holiday in Jersey after Irene's death

Growing up, Iain had many nightmares about his mother dying, in which he'd see himself running down a hospital corridor away from a blazing fire. He still remembers those dreams vividly, as he does the feeling of losing his mother, which stayed with him long after her face had faded from his memory.

But whenever he tried to talk to his dad about his mum it always seemed to hit a raw nerve - Don would immediately well up and Iain would resolve not to push it. And aside from his grandmother - whom he'd occasionally chat to about Irene - nobody else really seemed willing to talk about her. So Iain grew up with almost no idea what she'd been like.

A year or so after Irene died, Don met Judith who later became his second wife. Judith and Iain quickly became very close - "almost like birth mother and son," Don says. But Iain never talked to his new mum about Irene either, and remembers crying when she went into hospital to give birth to his half-sister - he was worried that like Irene, Judith might never come back.

Iain and his father, Don

Over the years Don fell out of touch with most of Irene's family and many of their old neighbours and friends. Looking back he's not exactly sure why he didn't talk to his son about Irene more - he was just trying to cope, the best he could.

"What understanding would he have had at that age? I don't know. It's very difficult to decide when to tell someone about something like that," Don says.

"When you build a new life you don't want to keep going back over what happened before - you're just concentrating on being a family together."

And so it wasn't until Iain's 18th birthday that Don brought the box of Irene's belongings down from the attic for the first time. Together they dusted it off and sifted through the photos and mementos that told the story of a woman Iain could no longer remember.

Iain held on to his baby book, but then the rest of the box was repacked, carried back up the ladder and put away again. And nothing more was said about Irene.

Iain pictured recently with his wife and children

By his early 30s, Iain had married and become a parent himself. As his eldest daughter approached the age that he had been when his own mother died, Iain decided it was time to try to fill in some of the gaps in what he knew about Irene.

"When you have a child that age, coming up to three, you see that they're a fully rounded and emotional human being, and I found myself wondering more and more about what happened to Irene and the impact that had had on me," he says.

"I wanted to amplify her a bit and celebrate her as a person - but first I needed to find out who she was, I really didn't know anything about her."

Iain asked his father to bring down the box from the attic for the first time since his 18th birthday. Then he placed an advert in the Nuneaton Telegraph asking people to contact him if they'd known his mother, and stuck posters to lampposts. Over time he tracked down Irene's closest friends, school classmates, relatives, old neighbours and former colleagues, who each shared stories and photographs of the Irene they'd known.

"There were all these photos, bits of my mum, scattered around in other people's houses," Iain says. "And she was still living in people's heads - that's what I wanted to gather up."

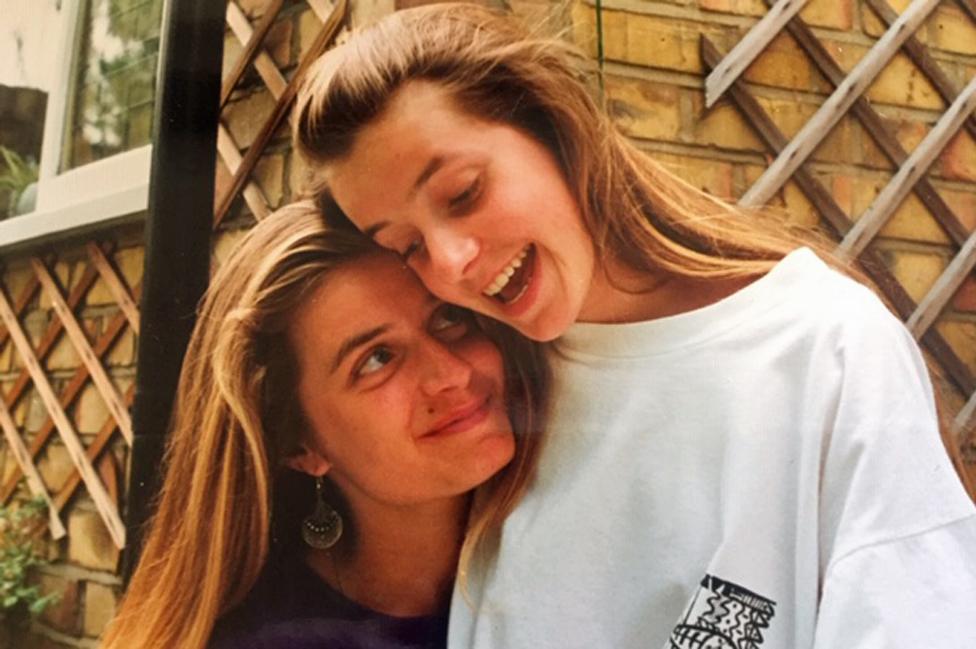

Irene (on the right in both photos) and her best friend, Lynn, aged 16 or 17 - the pictures were taken in Margate photo-booths

People would tell Iain how much he looked like Irene, and sometimes he'd find it a bit overwhelming to see new pictures of her. But through the pages of strangers' photo albums, the letters they'd hung on to all these years and the shared experiences they'd never forgotten, he built up a detailed picture of a quiet, gentle, artistic girl who was always laughing, who'd been the local carnival queen, and who, as she grew older, loved dancing on Friday and Saturday nights, and taking trips to Margate to sunbathe and see the shows.

"I'd never seen a photo of my mum until I was 18, and even then just the ones in the box," Iain says.

"There weren't that many and in a lot of them she wasn't well. So to see her as a young, vibrant, colourful person having a good time brought her back to life. I'd had so little to go on, but I really got a sense of her fun and I felt very connected to the person that I'd made of her."

Iain found Lynn, his mother's best friend, and together they went to Margate where Lynn and Irene had holidayed in their youth

But Iain still had many unanswered questions. He'd always worried that he was in some way responsible for what had happened to his mum. Don, too, had never fully understood why Irene had died, and the people Iain had found who'd known her seemed to tell conflicting stories.

It took more than two years, but after a long search and an even longer wait for permission, Iain eventually managed to get access to Irene's medical records.

"And when I opened them they had the answers to quite a lot of the questions that I'd had," he says.

Some people had said that Irene had had a difficult time while she was in labour, others said that her heart had stopped beating - but the records described a normal birth.

"I think there was confusion at the time about what happened," Iain says. "And mental health was something that people found harder to talk about then - there's still stigma around it today."

Iain showed his mother's medical records to doctors who have helped him and his father make sense of what was most likely happening to Irene at that time.

"The description here is very clearly that of a postpartum psychosis with further episodes of what we would now call bipolar disorder," said Dr Alain Gregoire, an NHS consultant specialising in mother and baby psychiatry. "About one in 500 women develop this illness after childbirth."

Postpartum psychosis

Postpartum psychosis is a rare but serious mental health illness that can affect a woman soon after she has a baby

Symptoms usually start suddenly within the first two weeks after giving birth, but it can take several weeks

They may include: hallucinations; delusions (beliefs that are unlikely to be true); a manic mood (talking and thinking too much or too quickly); feeling "high" or "on top of the world"; a low mood; being withdrawn or tearful; lacking energy; loss of appetite; anxiety or trouble sleeping; loss of inhibitions; feeling suspicious or fearful; restlessness; feeling very confused; behaving in a way that's out of character

Most women with postpartum psychosis need to be treated in hospital

Another doctor told Iain that the antipsychotic drugs that Irene was being prescribed were toxic to her heart, and that the "heroic doses" she was being given could have led to her death.

"But it's hard to say with absolute certainty now," Iain says. "If you read between the lines, she was sedated the night before [she was found dead] because she was restless and noisy, and that can cover a multitude of things."

Having built up a vivid picture of the girl Irene had been and the woman she had become, it was immensely painful for Iain to read about how traumatic her time in hospital had been. But among the medical notes he also discovered transcriptions of conversations his mother had with the medical staff.

"And it was so nice to read things in her voice," he says. "She said she loved her husband and she liked the boy - I didn't quite get her love but I got a like, so I was pleased to read that."

Where to get help

Action on Postpartum Psychosis, external has more information for women and families affected by postpartum psychosis, as well as online forums which connect people in the UK to recovered volunteers

Help and support is also available via the BBC Action Line

Although they avoided talking about Irene for almost 40 years, Iain and his dad are much more open with each other now.

"It was a conversation that we needed to have and it's been really helpful for both of us," Iain says.

"I understand more about what my dad went through and maybe just didn't have the tools to be able to talk about."

Don is also relieved to at last have a better understanding of what happened to his wife.

"I couldn't tell him because I didn't know," he says. "So to get that information, finally there was an explanation of how she died. I think Iain and I have got closer, and I've become much easier to talk to."

Don and Iain on the Nuneaton street where Iain grew up

The box of Irene's belongings that sat untouched for so many years in Don's attic lives at Iain's house now. The gilded dressing table set, the good luck charms from the wedding and the ballerina music box are all still safely stowed beneath the lid.

From time to time Iain and his daughters take a look inside at the things that once belonged to the grandmother the girls never had the opportunity to meet, and they talk about Irene and why she's not around to see them grow up.

"It's good to be able to softly introduce these ideas because it's important kids learn about mental health," Iain says.

This tiny framed photograph of Iain's parents is no bigger than a matchbox

There were never any photographs of Irene on display when Iain was growing up, but Iain's eldest daughter has a picture of Grandma Irene in her bedroom, and there's a portrait of his mum and dad taken in the 1970s that sits on Iain's desk.

"I feel like I have a relationship with the real Irene now, and she's not something which isn't talked about any more," Iain says.

"I got the 'like' from her in the medical records, but people I found told me how much she did love me, and that meant a lot."

Photos courtesy of Iain Cunningham unless otherwise stated.

Iain Cunningham's film, Irene's Ghost, is on Sky Documentaries on Monday 22 June 2020 at 21:00 BST.

You may also be interested in:

Jen Wight lived in fear of mental illness after her elder sister, Jo, was sectioned when they were teenagers. But by the age of 36 she had a good job, was happily married and had just given birth to a healthy baby. It seemed that she had been worrying for no reason.

Postpartum psychosis: 'I always feared I'd go mad, and when I had my son I did'