'The love letter to my neighbourhood that helped me flee my country'

- Published

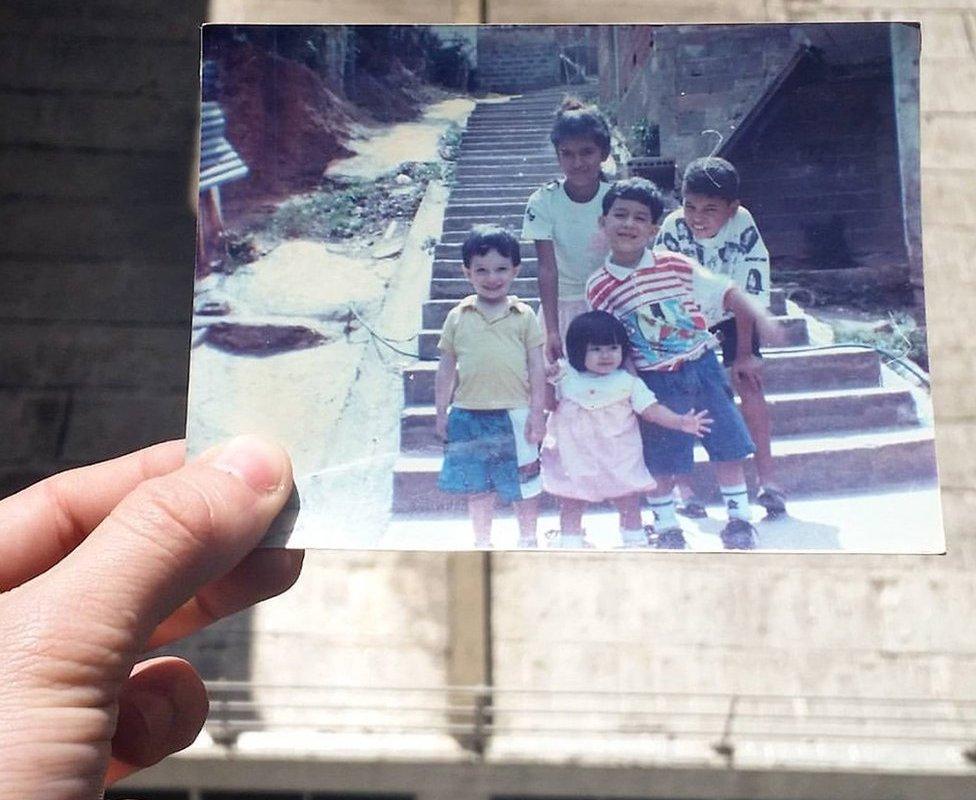

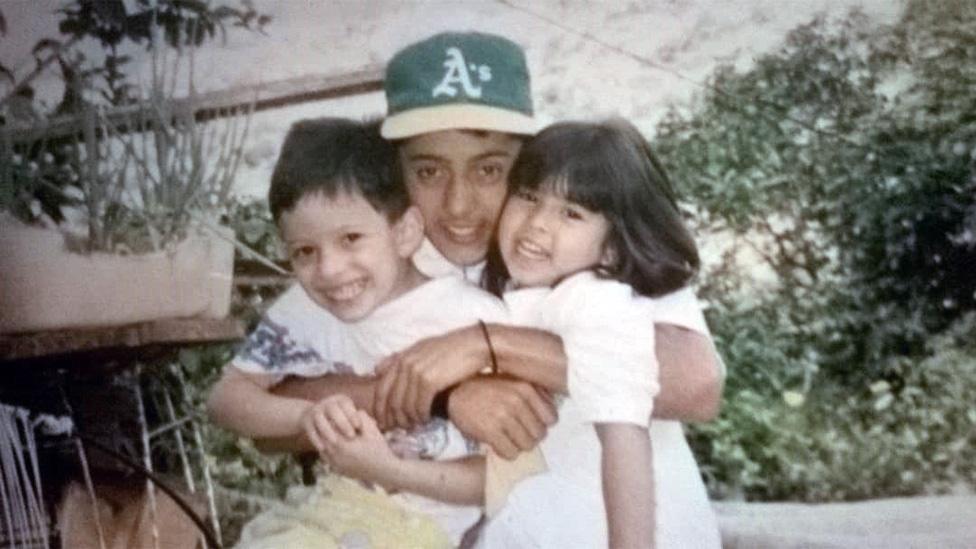

Jose (left) with his cousins and a niece in Nino Jesus in the '90s

As a journalist in Venezuela, José Gregorio Márquez reported from poor areas of Caracas, while being careful to hide his own humble beginnings. But years later, a love letter to the neighbourhood he'd felt so ashamed of would be his ticket to a new life abroad.

When José Gregorio Márquez was a child, he used to love writing plays for his classmates at school. He particularly remembers one about a group of animals who picked on a rabbit and bullied him.

"My message there was that we are all equals and we need to treat people decently. At the end of the story, the other animals got to know the rabbit they didn't like at first, and grew to love him," he says.

He also used to imagine stories for his toys, with each new tale entertaining and keeping him company for up to a week.

It was a form of escapism for the young José.

"Most of the time I was at home alone. My mum used to work the whole day, and I didn't have anyone my age to play with," he remembers.

"All these games were a distraction. I was creating the world that I wanted to live in, which was very different from the world I was living in."

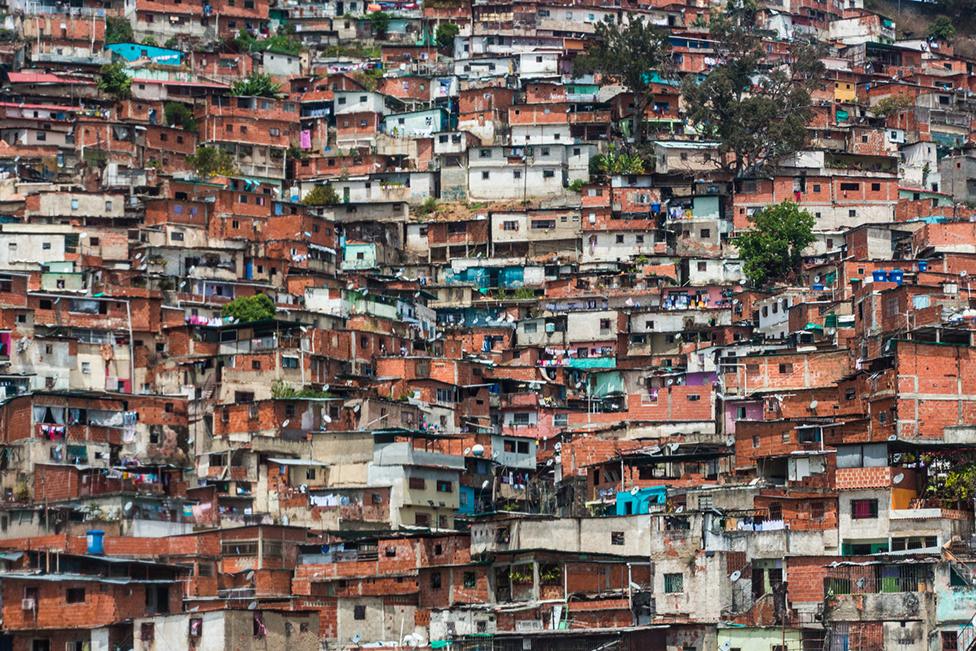

That world was Niño Jesús, a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of Venezuela's capital city, Caracas. Gangs controlled the streets, so José's mum, a cleaner bringing up four children alone, didn't allow him to leave the house.

"Many mums in the neighbourhood thought that was the way to make sure you don't become a criminal," he says.

José was nine when Hugo Chávez, a former paratrooper, came to power promising a socialist revolution. To low-income families, like those in Niño Jesús, he was a hero, at least to begin with.

José was used to seeing Chávez on TV. Every Sunday the president hosted a talk show called Aló Presidente, where he took calls from people across the country. But it was watching a political crisis unfold on television that inspired José's career.

"I actually remember the specific day I decided I wanted to be a journalist," he says.

It was 11 April 2002, two days after the start of a general strike. A huge demonstration made its way to the presidential palace, gunmen started shooting into the crowd and 19 people died, including a photojournalist.

A policeman holds up his gun during clashes in Caracas on 11 April 2002

José, who was 13, watched the events unfold live on television. Then the picture changed: Chávez was giving a national address.

"The channels divided the signal, showing an urgent message from Chávez on one side of the screen and on the other they continued to show the demonstrations."

But within minutes the government succeeded in cutting off live coverage from the street.

"So one side of the screen was black and the other had Chávez," remembers José.

"For me, it was very shocking not to be able to know what was going on. But it was also very shocking to see all those journalists trying to get the information, despite all the risks. So then, almost an obsession with journalism started."

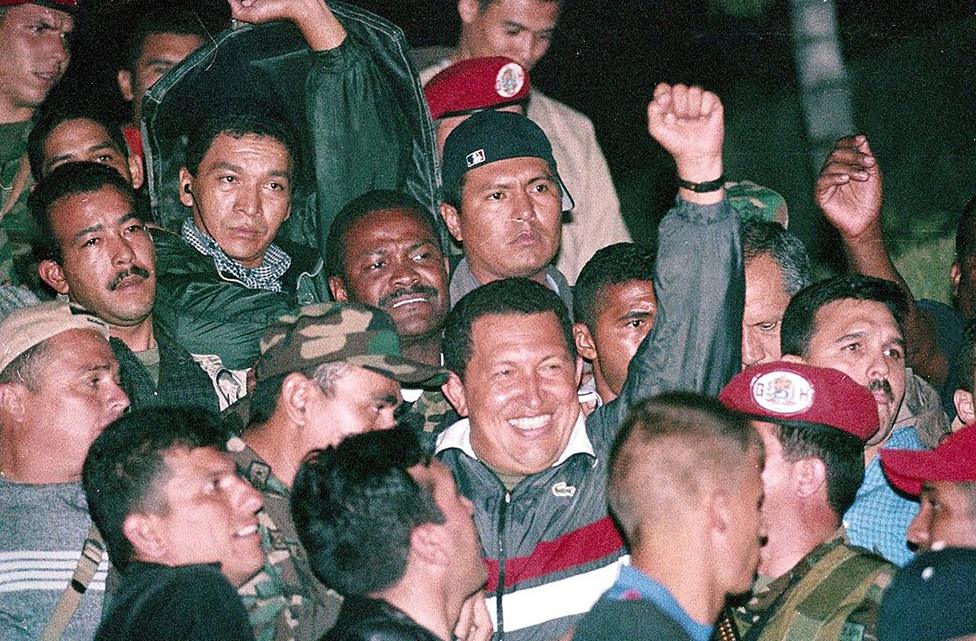

Within hours of his broadcast, Chavez was forced to resign by the military high command, but 72 hours later - after huge demonstrations by his supporters - he was back in charge. From then on, he set about dismantling the private TV networks, which he felt were against him.

Hugo Chavez returns to office shortly after he was ousted

But José was set on his path, and in 2008, while studying for a degree in Social Communication, he joined a daily newspaper called Últimas Noticias as an intern, and worked his way up to writing for a section called Ciudad (City).

"It consisted of collecting information from the neighbourhoods of Caracas with people's demands for the government. So it was more or less what I had lived in my own life. Now I could give a voice to all those people and publish their stories."

But José always kept it a secret that he lived in Niño Jesús.

"I used to hide it completely. I didn't tell anyone that I was from there," he says. "I was ashamed of the area I came from, despite being a reporter for other neighbourhoods where humble people lived, who were demanding improvements."

Jose reported from poor neighbourhoods like the one where he grew up

This was a challenging time to be a journalist in Venezuela. Chavez had grown increasingly tyrannical and journalists were now at risk of imprisonment if they criticised a government official.

José felt like he was coming of age as a journalist just as press freedom was disappearing.

The daily newspaper that José had been working for ended up being nationalised, like many other newspapers and television networks. Outlets that managed to avoid it, stopped holding the government to account, in order to avoid nationalisation or closure.

Find out more

In 2013, José started working for El Nacional, a newspaper with a 70-year history, which remained one of the last critical voices in the country.

"The government took every step possible for the newspaper not to have actual paper to be printed on," José remembers.

"It was interesting to be a journalist at the time, because sometimes you could write a headline that didn't make any critical reference, but then down in the news story, you could because the censors didn't read the whole story. So I did that a lot - until I was found out."

El Nacional ceased to be printed in 2018, and went online only

Later, while working as a cultural reporter for a newspaper, José was sent to review a performance by the daughter of a prominent politician, Diosdado Cabello.

She wanted to be a singer, and José watched the audience shouting and booing at her because of who her father was.

When his report was published, he was almost fired and the union of journalists had to step in to save his job. It was the last time he wrote something that could be perceived as critical of the regime.

For years José was waiting for the day when he could leave Niño Jesús. He wanted a better life - a home where he could feel safe, and had access to drinking water every day. In Niño Jesús, you could often only get it once a week, and there would also be periods up to 20 days long where there was no access to water at all.

So, in November 2012, a few months before he graduated, José moved into an apartment in the Altamira neighbourhood of Caracas, sharing a room with a friend to make ends meet.

But almost as soon as he left, something strange happened. The shame he had felt about the barrio for so long evaporated and was replaced by a fierce sense of love.

"As the saying goes, 'You don't appreciate what you have until you lose it.' I connected more with where I came from once I saw it from afar," says Jose.

He realised that the skills and experiences he'd gained growing up in Niño Jesús had shaped him in a positive way. "I guess I grew up," he says.

And within months an opportunity arose to tell the world about it.

A sunset over Nino Jesus

Even before Chávez came to power, Venezuela held a popular annual love letter writing competition.

"It was just another way to give some colour to people's lives in a country where everything is wrong and nothing works," José says.

Hundreds of people took part in the contest, and it became so successful it was eventually opened up to participants from other countries.

Most of the letters were written to loved ones, relatives, or even pets. But in 2013, when José saw the competition advertised, he felt inspired to do something different.

He decided to write about Niño Jesús.

"I was declaring my love to a neighbourhood, but it was also a way of telling the truth about how society looks away from these neighbourhoods, instead of looking at them and taking care of them," José says. "I made peace with the neighbourhood."

José had seen the violence, the crime, the death that Venezuelans associated with Niño Jesús. But he also wanted to show the colour, the life, behind all those stories.

"From far away, you didn't see the people who live in those little houses, people who love and smile in those neighbourhoods," José says. "So my intention was to put that into words, telling how I came to love and understand the place, and understand that it had been very important to the person I was becoming."

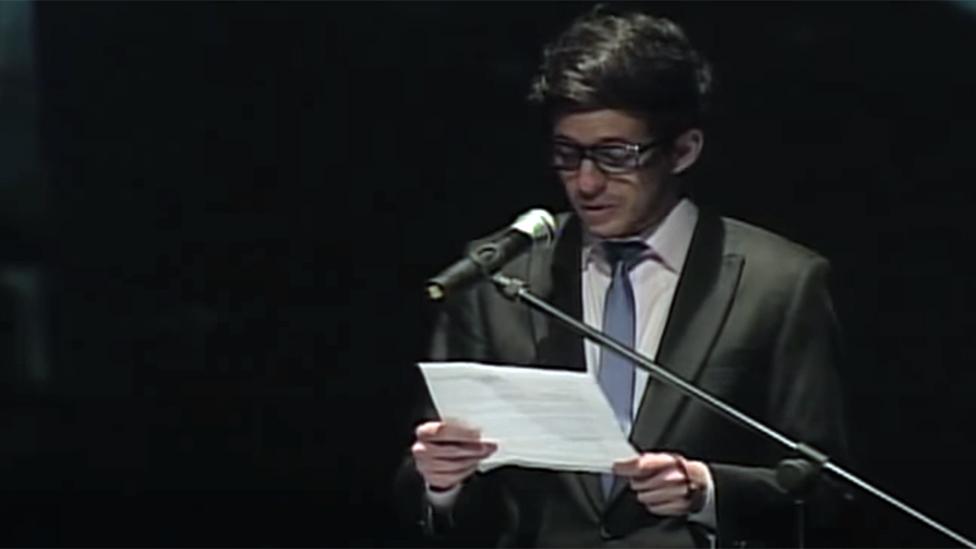

José was selected as a finalist in the competition and was asked to read his love letter in a theatre in Caracas, external.

"Dear Niño Jesús, I still remember your abstract shapes and your misshapen shadows," he began.

Although when I lived in your streets and walked your stairs, I'd rather just look up at the sky because it was the only thing I liked around me. I was an idiot...

You're not to blame for anything, but I wanted to be far away from you.

I used to hate waking up at four in the morning to fight for a seat on the bus that would take me to work.

I hated going up or down each of your damn steps. I hated the zinc roofs that didn't stop the stones, the raindrops, or the bullets. I hated the sheets spread over stiff bodies that could no longer feel the cold of the asphalt. I hated you.

Now, however, I miss you.

I miss the kites undulating among the clouds like roving sperm. I miss the green of your trees, next to the orange of your bricks, caressing the blue of your water tanks. I miss the impudence of the roosters at dawn and the eloquence of the cats at dusk. I miss you.

Although I understand how important you were to building my life, I was always ashamed of you. I denied knowing you.

And I'm sorry.

I never belonged to you as much as I do now, when I am without you and you are without me. I had never realised before that I loved something I'd already lost.

I never asked you for anything before, but this time I'm asking you to forgive me...

I came from you and I will always be yours.

José

After a moving performance, much to his surprise José won the competition. As he walked up on to the stage he thought there must have been a mistake, and that the judges had intended to name one of the other finalists - some far more well-known, and with beautifully written letters.

Jose Gregorio Marquez reading out his award-winning letter in 2013

José was awarded a watch worth $5,000. He knew it was an insurance policy, a way of getting money if he really needed it, and concealed it carefully in his underwear drawer.

About a month later, his apartment was burgled and many of his valuables, including his laptop, were stolen.

But his watch remained safely hidden under his socks and pants.

President Chávez died in the same year as Jose won his prize, and Vice-President Nicolás Maduro took over. Simultaneously, with falling oil prices and inflation rising, the country's economy went into freefall.

"You just couldn't get food," José says. "They assigned all citizens a day of the week to buy groceries according to your ID card number. My day was Friday, but normally food got delivered on Monday. So by Friday, you wouldn't have any food in the supermarket any more. If I tried to buy on Monday, I wasn't allowed. It was just pure, utter despair. It was very humiliating and very sad."

By 2015, unable to live off of his income as a journalist, José started thinking about leaving Venezuela. But first he moved back to his childhood home.

"My mum was still living there, and given that I couldn't have any way to take my family with me at the time, it was nice to be with them. It was a good way to say goodbye and it was actually lovely to get back to the place I had grown up, to see those colours again."

Jose (left) with one of his older brothers and a niece in the 90s

José found the idea of leaving extremely difficult because he feared he wouldn't be able to return as long as Maduro remained in power.

But the country he knew no longer existed. Things had been changing so rapidly and deteriorating so quickly. And he realised that even if he had to leave the country, he'd never again leave behind that part of himself that was forged in Niño Jesús.

José knew that in order to leave he would need US dollars, but the value of the Venezuelan currency, the bolívar, had sunk so low they were virtually unobtainable.

So he asked a friend who was travelling to the United States if he would take his watch and sell it. He agreed, but was only able to get $1,500 for it - $3,500 less than its actual value.

That was enough, though. He decided to emigrate to Buenos Aires with a friend who lent him the money for a one-way ticket. He would use the money from the watch to help him survive once he got there.

José had previously visited Argentina in 2011, and already had friends living in the country. He liked the openness of the culture, and, vitally, he believed he'd be able to get a residence permit.

After saying an emotional goodbye to his family, José arrived in Buenos Aires, with photographs and bolívar coins and tickets as memories of his life back home.

He expected to land on his feet. After all, he'd been a successful journalist at respected publications in Venezuela, and thought this would make it easy for him to find a job in journalism.

But it wasn't to be. He spent his first month feeling sick, unused to the cold Argentinian winters, and had no leads for job interviews. He decided to start working in a cafe, which he says helped him grow as a person, and learn to work as part of a team.

"It made me see that nothing can be taken for granted in life, and that you can always start from scratch. To start from the beginning, without ego."

Six months later, he was able to find a job in an advertising agency.

In the four years since he left Venezuela, José has not returned. And he doesn't see that changing while the government continues with chavismo - the political system and ideology established by Chávez.

There are things that he misses - most notably, the beach, the weather, and the El Ávila mountains.

But these are not reasons enough to leave Argentina.

"Not only because of the current economic crisis, but also because I am gay and Venezuela is a homophobic country where LGBTI people have no rights and are constantly mistreated," José says.

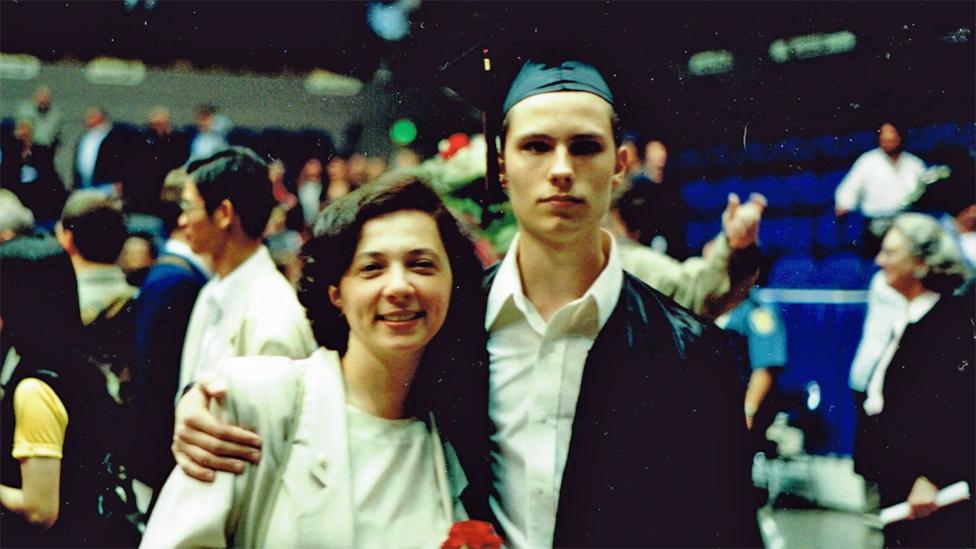

In February, after saving for many years, José moved his 70-year-old mother to Argentina. He wanted her to live comfortably in her later years and this would not have been possible in Venezuela.

Jose and his mother, Alida, now live in Buenos Aires

José says his love letter to Niño Jesús changed his life.

"It made me feel validated, not only as a human being, not only for my story of humble origins, but also for what I had to offer as an aspiring writer who, until then, always felt that I did not have enough talent, even though I had been writing for newspapers for years," José says.

"That award is so important in my life, it allowed me to emigrate from the country, flee from the crisis, and it continues to bring me closer to incredible people from all over the world."

Listen to Jose speaking to Outlook, on the BBC World Service (producer, Tom Roseingrave)

You may also be interested in:

As a gay teenager in post-Soviet Russia, Wes Hurley breathed a sigh of relief when his mother married an American and they moved to the US - but he soon discovered his stepfather, James, was violently homophobic. This led to strained relations, until James underwent an unexpected transformation.