'My 30-year struggle with racism in the Metropolitan police'

- Published

Shabnam Chaudhri rose to become one of the Met's most senior female Asian officers, but she says she was unfairly treated throughout her career because of her ethnicity. Her experience highlights concerns about the treatment of BAME officers in the UK that have persisted for years, write the BBC's Oliver Newlan and Home Affairs correspondent Danny Shaw.

Shabnam Chaudhri always wanted to join the police. Growing up in London's East End she and her family regularly experienced racism, and she was determined to prevent others going through the same ordeal. "We had our windows smashed, had racist flyers put through our door, white families would abuse us verbally," she recalls.

One night, returning from the mosque where she taught, Chaudhri's mother was the victim of a racially motivated assault. A few days later her mother returned to their home with a new pair of trainers. When Shabnam asked what they were for, her mother explained it would be so she could flee attackers in future, and carry on her work at the mosque. "It taught me you could stand up to racism," she says. "From a young age I wanted to make a difference."

This report includes very strong language

Thinking like a detective came naturally to Chaudhri. In her teenage years when working in a clothing shop she developed a skill for catching criminals. "I had a real eye for catching shoplifters and credit card fraudsters. I'd get the police to come and they'd say 'You're really good at this sort of stuff, why don't you consider a career in the service.'"

It took a while for this to become a reality, however.

Chaudhri's family wanted her to marry first.

Listen to Shabnam Chaudhri's story on File on 4 - Racism in the Police at 20:00 on Radio 4, on Tuesday 30 June - or catch up later online

"The community didn't feel it was appropriate for me to be walking the streets of London, so my parents were trying to get me married off. It took me two years, but I finally managed to bat off all the potential suitors I was introduced to," she says.

Then her first three applications to join the police were rejected. They told her she was too skinny, too young and lacked relevant "life experience". It took six years, but she was finally successful in 1989.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Working in Bethnal Green, Chaudhri had landed her dream job. She was out nicking the bad guys, something she'd always wanted to do. However, she says it wasn't long before the racism she hoped to fight through policing became evident within the police itself. Shabnam says she experienced racism from some of her colleagues; at the time she considered it just the normal banter that was insidious throughout the organisation.

"They used to call me the 'Bounty'. On one occasion an officer grabbed hold of me, put a weapon to my head and said, 'Everybody stop or the Paki gets it.' I just wanted to get on with the job, so I accepted it as part and parcel of being an officer."

Chaudhri progressed to the rank of detective sergeant, but in 1999 - the year of the Macpherson Report into the death of black teenager Stephen Lawrence - she made an official complaint of racism that she says held back her career.

One of the recommendations of the report, which labelled the Metropolitan Police "institutionally racist", was that officers were to undergo racism awareness training. But after one of these sessions Chaudhri complained that an officer had mispronounced "Shi'ites" to make a bad-taste joke, and referred to Muslim headwear as "tea cosies".

Instead of feeling supported when raising the grievance, Chaudhri says she was subsequently victimised. "Over a very, very quick short period of time the job that I loved suddenly became somewhere that I was scared to work… My position became untenable. Stuff went missing off my desk. My team stopped talking to me, and I'm thinking, 'How am I supposed to do my job? How am I supposed to investigate crime, deliver a service to the people of London, to victims of crime, when I can't even sit in an office and do my job?'" Chaudhri felt she had no choice but to move boroughs, but she says she had now been labelled as someone who "plays the race card" and as a "trouble maker", and this affected her relationship with her new team.

The case led to lengthy legal proceedings, which proved to be embarrassing and costly for Scotland Yard. In 2005, it had to pay damages to the officers she'd accused, because an Employment Tribunal ruled the force had treated those officers unfairly. Met commissioner Sir Ian Blair criticised the tribunal's ruling, external.

Concerns that when officers raise racial grievances within police forces these aren't dealt with appropriately, and that the officers who raise them face a potential backlash, are long-standing. In 2005 the then Commission for Racial Equality produced a report into how police forces deal with racism internally.

"There was a general feeling from a number of our correspondents that grievance procedures were operating to their disadvantage," says Sir David Calvert-Smith, who led the team that produced the report.

Noting that there has been a tendency for officers who raised grievances to be victimised, he says: "It's absolutely shocking and anybody who indulged in that sort of behaviour would be unfit to be holding [their] position."

Clear recommendations were made to prevent the problem resurfacing in future.

Despite this, 10 years later, in 2015, Scotland Yard was scolded by another employment tribunal, after revealing it was official policy that those investigating internal grievances should not make findings of discrimination.

Reflecting on the progress made since 2005, Sir David says the lessons have not been learned.

The Metropolitan Police told the BBC there is "no place for discrimination or victimisation" in the force. It acknowledges grievance procedures had been in need of a "complete overhaul" but says it has now made the necessary improvements, including setting up a dedicated Discrimination Investigation Unit.

Following her complaint Chaudhri led a burglary and robbery squad, but she describes the next stage of her journey with Met as a "mixed bag".

"In fairness to the Met they did try to address the inequalities for black and minority officers and introduced good processes, but there wasn't a full cultural transformation," she says.

It all came to a head for Chaudhri in 2015 when, after completing a training course designed to help BAME officers to progress in their careers, she was successful in her initial application for a role as a staff officer at the Inspectorate of Constabulary, the policing watchdog known as HMIC.

"I had the skill set, I'd been a detective chief inspector. I'd done a stint as a uniformed chief inspector, I had done a huge amount of work around communities. I understood the fight around knife crime, hate crime, so had quite an extensive portfolio. I applied for the post, was successful and I even had a leaving do."

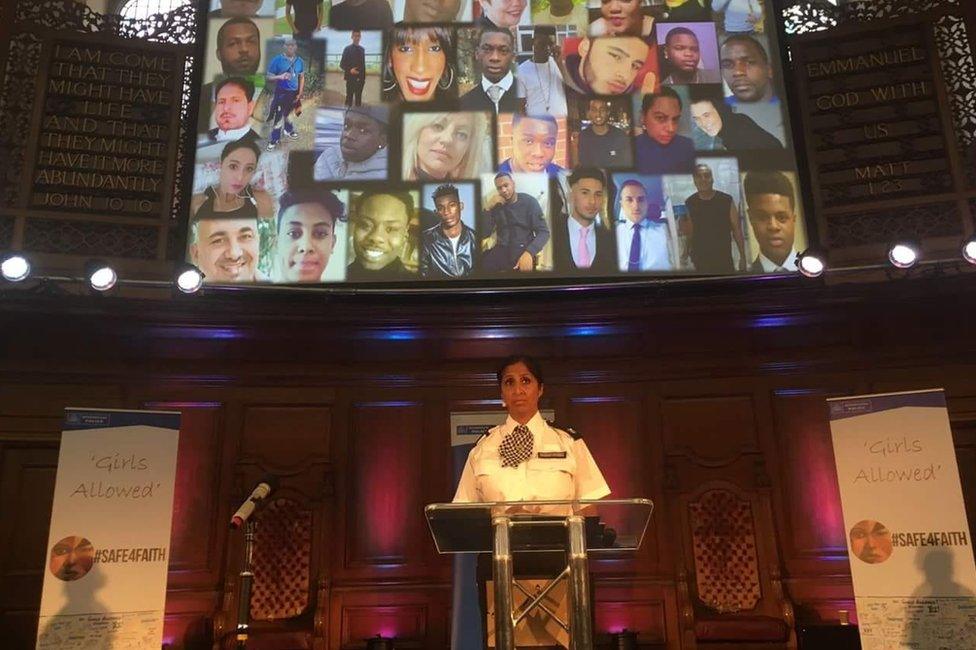

Shabnam Chaudhri calling on women to help prevent knife crime in their communities in 2018

But the offer was suddenly withdrawn. It emerged there had been a problem during the vetting process. Chaudhri had declared she knew someone whose family may have been involved in crime. The Met's Professional Standards Departments (PSD) graded the association as "medium risk", ruling her out of the job. It was later downgraded to "low risk" - though by then it was too late. In a letter to the PSD, HMIC made clear they were disappointed with the way the department had handled Chaudhri's application and welcomed the decision by the department to conduct a review of the pre-employment process.

For Chaudhri, however, this was more than a bureaucratic error. It indicated there was a culture within some elements of the Met where unfounded prejudices about officers from ethnic minorities still remained.

"I think there's an unconscious bias within Professional Standards. You have people that have worked there for years and years and years who are set in their ways, who have certain views against certain sections of the community. I've been brought up in the East End and I live in Essex and undoubtedly I will have come into contact with people that may have some criminal associations. But I had made the decision not to have any further contact with that individual. I think I wasn't believed at face value because of a stereotype that BAME officers associate with criminals."

Scotland Yard says it has altered its employment and vetting process to make it "smoother". It says all officers now have training in unconscious bias, diversity and inclusion.

Chaudhri isn't the only officer from an ethnic minority background to experience problems with career development. Promotion has often been a struggle for ethnic minority police officers: there are only five at the most senior levels in England and Wales, and only one force, Kent, has ever had a black chief constable.

Previously unpublished Home Office figures seen by the BBC show how specialist police units too continue to be dominated by white officers. Last year there were only two ethnic minority officers among 184 in the mounted police; 15 out of 734 dog handlers; and 11 among 426 detectives in special investigations teams. The Home Office collected the data on the principal roles of officers from 42 forces across England and Wales. The proportion of BAME officers was higher in some other specialist roles.

Deputy Chief Constable Phil Cain, the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) lead for Workforce Representation and Diversity, says the organisation needs to develop a proper development programme for officers and staff to rise through the ranks or into specialised departments.

Minister for Crime and Policing Kit Malthouse said: "Our current campaign to recruit 20,000 additional officers gives us a once-in-a-generation opportunity to bring more diverse candidates into police forces across England and Wales."

After the vetting fiasco Chaudhri obtained a leadership position working as an acting superintendent for the Met's East Area. But just as she applied for a permanent role as a superintendent, she found herself at loggerheads with her PSD again. An anonymous caller had claimed Chaudhri hadn't recorded her work hours properly and had been falsifying entries on a computer system. She'd been warned before about the need to document her hours. Chaudhri was placed under investigation over allegations of gross misconduct.

"I was devastated. It kind of came like a bolt out of the blue! Of course, I recognised how serious it was, it's a sackable offence. I could have lost my job," she says.

"It begs the question, why do people feel the need to anonymously complain about my booking on and booking off? Why didn't the organisation think, 'Hang on a second, this is a prevalent problem, particularly among senior officers, let's have a look at that first?'"

The Met says it has a duty to "thoroughly investigate" potential wrongdoing, pointing out that other senior officers have been investigated over similar allegations.

Shabnam Chaudhri speaking to the media after the murder of Jodie Chesney in east London, in March 2019

While under investigation for gross misconduct Chaudhri received the Outstanding Contribution prize at the No2H8 Crime Awards, run by a variety of third sector organisations, for her passionate work tackling hate crime.

"My work - through workshops and outreach work - supported under-represented groups, bringing communities together to eradicate hate crime," she says.

"I felt honoured to win the award, and it felt like vindication for the work I was doing."

Although she was cleared of falsifying her working hours, and of gross misconduct, she was found to have complied poorly with timekeeping rules and was given advice on using the "booking on" system correctly. Then she finally got the job as superintendent. But the seven-month investigation had taken its toll on her, and proved to be the final chapter in her long career.

"I got diagnosed with PTSD. I developed tinnitus. I used to walk from Scotland Yard to Blackfriars and I would call my sister, crying down the phone because I was so gutted that I was going to lose my job. It warranted me to leave after just over 30 years. I'd love to have stayed for 35 years but if I stayed I'd have been watching my back. I'd be scared every time I got a phone call, thinking, 'Are they watching me? Have I done some something wrong?'"

She retired in December 2019.

Figures on the ethnicity of those involved in police misconduct cases are not publicly available, but the BBC has seen figures obtained by the National Black Police Association (NBPA) through Freedom of Information requests made in late 2018. Thirty-two policing organisations responded in full.

Out of more than 9,000 officers who were being investigated, about 1,300 were from an ethnic minority - over 14%. Where inquiries had progressed to a misconduct meeting or gross misconduct hearing, 340 ethnic minority officers were involved out of about 1,600 - that's more than 20%. And yet less than 7% of police officers in England and Wales are from ethnic minorities.

Tola Munro, President of the NBPA, says the figures are significant because BAME officers are not over-represented in complaints made by members of the public, only in complaints submitted from within the police.

A number of reasons have been suggested to explain the disparity. Some people say the misconduct process is used against officers from ethnic minority backgrounds. Another explanation is that managers are less likely to address misconduct issues informally, when they concern BAME officers, for fear of being accused of racism.

The trend thrusts a spotlight upon professional standards departments which carry out misconduct investigations into officers. Research published earlier this year by the NPCC found 63% of PSDs across Home Office forces didn't have a single BAME officer. But despite numerous reports published over the last two decades, highlighting the over-representation of BAME officers in the misconduct process and suggesting clear recommendations, the problem persists.

The NPPC's Phil Cain says: "I am really sorry about the experiences those officers and staff members have been through in the past. We are now looking to work with the College of Policing to look at how we can introduce some additional training that requires supervisors to look at dealing with issues at the lowest level at the earliest opportunity."

Minister for Crime and Policing Kit Malthouse said: "We've recently introduced an ambitious package of reforms to make the police misconduct process more transparent and proportionate - and this is a real opportunity for police leaders to make the system fairer for all officers."

For Chaudhri though, the renewed promises of change have come too late. "I loved the organisation, don't get me wrong, but I didn't feel safe after that had happened," she says.

Reflecting on her experiences in the wake of the killing of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter UK movement, she says: "If you are not going to get your house in order you won't get trust in communities. The police have got to be seen to be diverse. That can't happen if you see an all-white police service." She hopes recent events will serve as a catalyst for change.

Chaudhri, now 55, looks back fondly at her achievements as a female Muslim officer and is proud to have confronted racism head on within the force when she felt she saw it. "I loved the job, I loved helping victims of crime, and I loved being an officer. Given what happened to me in 1999, when I challenged the organisation around race and was subsequently victimised, I was never going to give up. I'm proud of that. I felt I served myself, my family and the service with dignity and respect. It's been one hell of a rollercoaster ride for me but I wouldn't change any of what I did."

You can hear Shabnam Chaudhri's story on File on 4 - Racism in the Police on Radio 4, on Tuesday 30 June at 20:00, and later on BBC Sounds

You may also be interested in:

Police stock image

"I have stayed silent. It's made me feel like I have been complicit in it. But my job is my livelihood, I cannot lose it." Black and Asian officers speak out about their experiences in the police.