Coronavirus doctor's diary: Why are people remaining ill for so long?

- Published

Molly Williams could squat with 105kg before she became ill

Four months after the start of the coronavirus pandemic, doctors are still on a steep learning curve. One surprise is just how long symptoms seem to last, for some patients. Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary (BRI) talks to two young women who are still tired and breathless many weeks after falling ill.

Amira Valli, 27, a doctor from a neighbouring hospital, has been getting out of breath when climbing a single flight of stairs.

Molly Williams, a 34-year-old physio at BRI, has always been a super-fit athlete but "being breathless is becoming my norm" she says. On top of that she is experiencing waves of emotion, and having difficulty with her memory.

For both of them, it's about three months since they first got sick.

Back in March we knew so little about this virus. We assumed that it was a respiratory illness, only to find out that it affects almost every organ in the body. We assumed that we would rely on invasive ventilation and ICU only to find out that early CPAP (non-invasive ventilation with oxygen) on the medical wards was more effective.

We also assumed that when we applauded our patients who had recovered from this acute viral illness off the wards that it would be the last we saw of them.

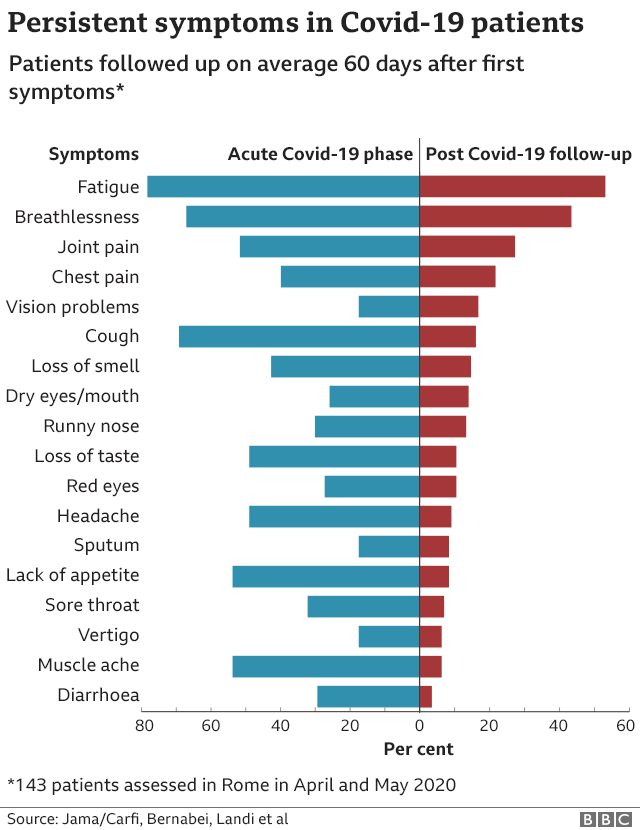

Four months on, and this new foe has become an old foe, and sometimes it seems our only foe. We have also become increasingly aware of the longer-term legacy for patients - not just those who have been in hospital, but those who have self-treated at home and recovered from the acute infection only to suffer from relapses and persistent symptoms. Patients who had the infection months ago are struggling to resume their normal lives.

We know from studies of patients who had Sars - one of the family of coronaviruses - back in the 2003 epidemic, that almost half of survivors went on to have chronic fatigue or other long-lasting symptoms. So it should not be a surprise that this cunning descendant, Sars-CoV2, should have a similar inheritance.

We are getting an increasing number of desperate emails and letters from patients and their GPs asking for help. Some are still suffering from the original symptoms of chest pains and breathlessness. Others have newer symptoms - headaches, memory loss and visual problems. Many have depression and anxiety. Most of them have persistent, chronic fatigue. All of them want their previous lives back. They celebrated their initial Covid-19 survival in haste and some are now filled with nagging doubt and deepening despair.

Dr Amira Valli and Dr Paul Whitaker

For the first week, Amira Valli's symptoms were quite mild - a headache, a sore throat, perhaps a slight fever. By the end of the week she thought she was coming out of it, but the next week she became breathless, and that breathlessness has stayed.

"I usually struggle with things like stairs. My heart rate will jump to 140 after I've climbed a flight of stairs. Last week I was having quite a bad week… I felt that I couldn't sleep, because I was too breathless. And obviously from that point of view, I was quite tired."

Amira also says she is starting to get anxious.

Her chest X-ray is normal, and her chest is normal to listen to. But something is not right and we will try to find out what it is.

Molly, second from left, with other physios heading on to the Covid wards, before she got ill

Physiotherapist Molly Williams volunteered to work on the Covid wards, and like Amira she almost certainly caught the virus at work in the hospital. An elite gymnast throughout her teens, she has since taken up CrossFit - she's one of the top 20 CrossFit athletes in the UK. But she too is experiencing breathlessness.

"My resting heart rate use to be 50 and now it's about 90," she says. "Even with talking I get breathless. I'm getting overwhelming muscular fatigue in my legs and my heart rate goes up to 133-plus on walking."

Molly says she also becomes uncontrollably tearful and "overwhelmingly upset about things". And she has been having problems with her memory.

"I'm forgetting things, and I'm repeating things a few times, I'm just not retaining information. If I try and remember a word I can't. I'm having to write things down all the time just to remember them," she says.

"I've no past medical history and for it to hit me the way it has is really hard."

Molly Williams as a young gymnast

We don't yet understand why these patients are having such long-term problems.

It is possible that the virus is lingering in reservoirs in their bodies and causing persistent symptoms, as we saw in survivors of ebola. Some of our patients are positive for the virus weeks after they first became infected but this is probably due to antigen-testing picking up residual fragments of the viral RNA. If so, these RNA fragments could be triggering a prolonged immune response that explains the persistent symptoms.

But more likely, these long-haulers are experiencing a prolonged and exaggerated immune response to the original infection, on top of the damage caused to their lungs and other organs.

Our challenge as doctors and researchers is to find out more about what causes these long-term effects and then develop treatments that help these patients, and others with similar post-viral chronic fatigue. This is a neglected area of research, because it is so difficult to find answers, but Covid-19 has been an incredible catalyst for science and discovery, and the spotlight on these long-haul survivors may help advance our understanding.

Front line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: Bradford worries about the whack-a-mole mallet

In the hospital, my colleague Dr Paul Whitaker has responded to the demand from patients by setting up our first Covid-19 survivors clinic.

Initially the plan was to follow up on patients 12 weeks after their discharge from hospital, but it's become clear that some people who needed hospital treatment are already back to normal, while some of those who didn't are still unwell, like Amira and Molly. So referrals are now being accepted from GPs as well.

When people arrive at the clinic they have chest X-rays, lung-function tests and a walking test, and are asked to fill in a series of questionnaires. If their symptoms are bad, then they may have an echocardiogram, a CT scan and full lung-function testing.

"I think there could be a big iceberg out there of people who've had Covid-19 and just haven't got back to normal. Every week I'm getting three or four phone calls from GPs who are saying they've seen a patient who had Covid a couple of months ago, and they're still symptomatic," Paul Whitaker says.

"In the clinic we're running we're going to be having a dietician, a physiotherapist, as well as a lot of psychological input, because patients are developing the cardiorespiratory complications, but they're also developing post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and they've got neurological symptoms and chronic-fatigue-like symptoms.

"And so how we can support them, how we can set programmes in place - either psychological programmes or rehabilitation programmes - is going to be really important. And we need good evidence about what works."

Rob Whittaker, a consultant clinical psychologist, says waves of tearfulness among Covid-19 survivors are very common and there is "an emerging picture" regarding cognitive difficulties, such as Molly's problems with her memory.

"But it's really hard at the moment to tease apart what's to do with fatigue and emotional, or what might be more organic. It's too early to say."

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter