'I was found as a baby wrapped in my mum's coat – but who am I?'

- Published

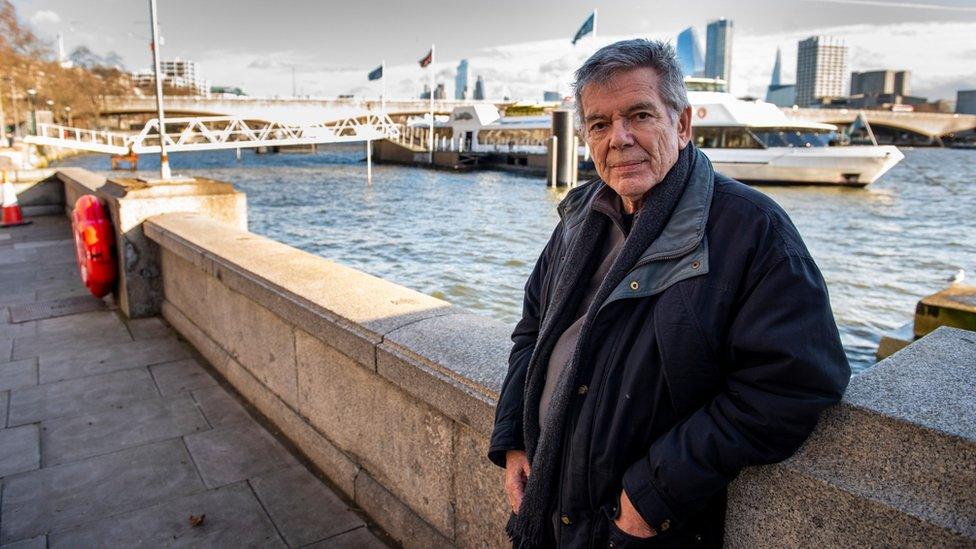

Tony May was only a few weeks old when he was abandoned by the River Thames in London, in the middle of World War Two. He had no idea who his parents were for more than 70 years. Then a DNA detective dug up the truth about his past.

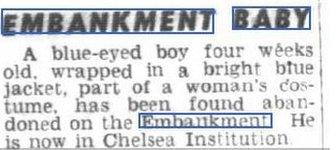

A few days before Christmas, in 1942, a baby boy was brought in to a police station near the Houses of Parliament in London.

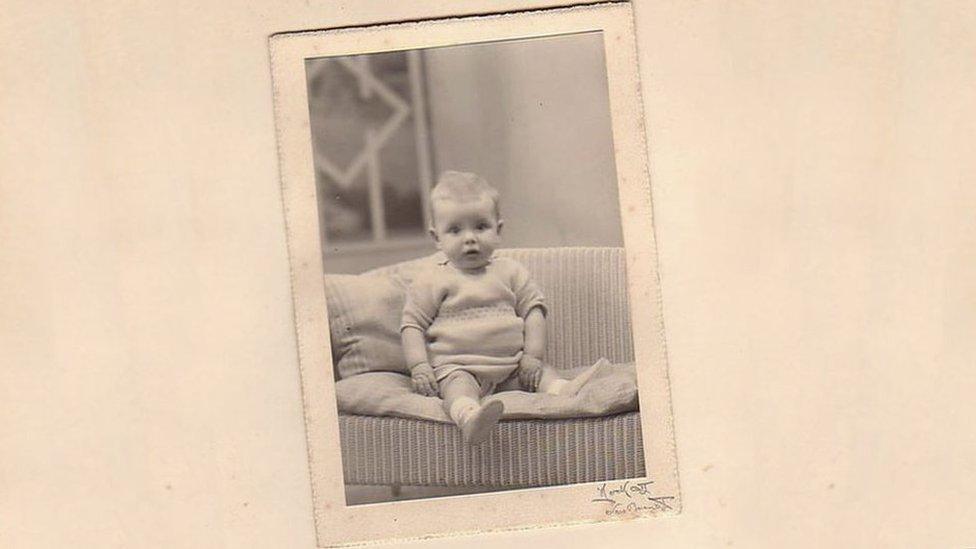

He had been found wrapped in a bright blue woman's coat on Victoria Embankment, a road lined with trees and occasional benches that runs along the north bank of the Thames. The boy was judged to be one month old and, after no-one came forward to claim him, he was allotted a birthday. He also needed a name. It was common at the time to refer to the place a child was found - and so he became Victor Banks.

"I always wondered who they were, you know? And why I would have been abandoned, I think that's the main thing."

Tony May is sitting in an old easy chair in his flat in St Albans, just to the north of London. There are jazz CDs piled on a side table, and photos of trumpet players on the wall.

"I used to run a club on the jazz circuit," he tells me. "We'd get musicians who had played at Ronnie Scott's."

Tony is in his 70s. Though he moves carefully around his flat his voice is full of energy. He gestures now to one of the pictures crammed on to his mantelpiece.

"My mum and dad, Arthur and Ivy, didn't have any brothers or sisters so they had friends who we called aunt and uncle. They were lovely to me."

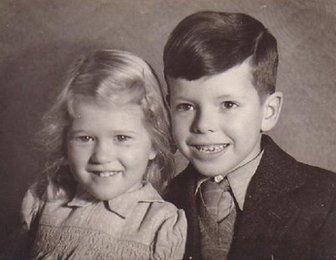

The couple adopted Victor Banks when he was a toddler in 1944, changing his name to Tony May. They went on to adopt a little girl called Eleanor who became Tony's sister. Tony remembers being told he was adopted when he was about seven.

"It was no big deal really. But I remember my sister went around telling everyone we were adopted and I was so embarrassed."

Tony and his sister, Eleanor

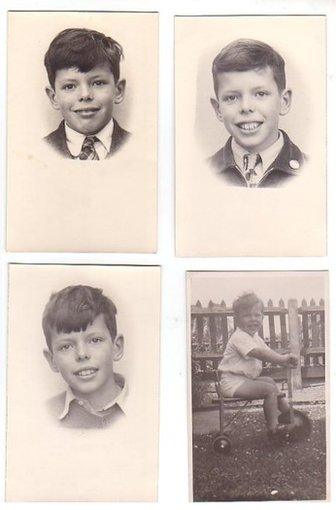

When he was growing up, Tony was particularly close to his father.

"My dad was very bright but although he was very interested in sport he was no good at it at all. When he realised I was good at it, he used to give me and my friend Mick cricket catching practice every night. He'd come home from the bank - I can see him now with his hat and umbrella - and he'd come down the garden to help us. And he'd take me to see major sporting events at White City stadium in London.

"I became a very good cricketer and schoolboy athlete because he believed in me. And when you're adopted you need people to believe in you."

Tony's adoption was rarely mentioned by his parents.

"I remember once my dad knocked on my bedroom door when I was a teenager and asked what music I was listening to," Tony says.

"It was John Coltrane on tenor sax playing ballads. He said: 'Do you think you play such mournful music, because you're adopted?' I said: 'No Dad, this is world-class music played all over the world.' He said: 'Oh, OK then.' That was that, there was no dialogue about it."

Tony only discovered he had been found as a baby on his wedding day, at the age of 23.

"My dad sidled over to me after the service," he says.

"He told me that when I got back from my honeymoon he'd have an envelope for me with my exam passes and adoption order. He said: 'There's a word on it that you might not know, the word foundling. Just letting you know.' I didn't twig for ages what it meant. It was much later that I realised I'd been abandoned."

Tony went into banking, like his father, and then into recruitment. He also had two children.

Looking back, he wonders whether not knowing where he came from did affect him, despite what he told his father about the music he'd been listening to that day.

"I worried a lot about things going wrong, which meant I worked extra hard at getting things right. It did mean when the auditors came around at work I knew I'd get a clean sheet.

"Though I laugh and joke and muck about, I'm not tactile. I'm fairly reserved, I would say, about showing emotion. But I can cry my eyes out watching a rugby match."

It wasn't until his adoptive parents had died that Tony felt ready to investigate where he came from. His first port of call was the London Record Office, where he was amazed to find out he wasn't allowed to look at his own adoption file. The rules at that time stipulated that a social worker had to go in and make notes in pencil on his behalf.

The file revealed that after being found on Victoria Embankment on 19 December 1942 he was taken to the old Canon Row police station near Westminster Bridge - but there was no mention of who had found him or at what time of day. After being examined at a hospital in Chelsea, he was evacuated to Easneye Nursery in Ware, Hertfordshire, away from the risk of bombing.

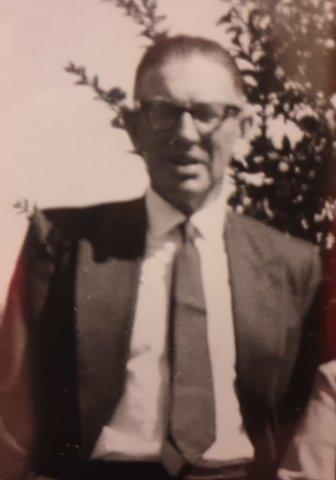

Ivy May

Little Victor first met Arthur and Ivy May at Easneye. Before they were allowed to adopt him they fostered him for a year and Tony is visibly moved as he reads out a welfare report from that time.

"Date on which visit made: 5 November 1943. Is the child well cared for? The answer is: 'She devotes her whole time and attention to the baby and he is responding well to individual care and is becoming interested in people and things.' Are the applicants satisfied with the child? 'They are very pleased with him and delighted to have a baby of their own.'"

"That's lovely, that," Tony says, tapping the table for emphasis.

Letters in Tony's file reveal the Mays wrote to the authorities to see if they could find out any more about his history. The reply was definitive - exhaustive inquiries had been carried out to trace the parents, but all efforts had been unsuccessful.

Having reached this dead end, Tony then took his story to the media in the hope it might jog someone's memory. He appeared on radio, TV and in newspapers in the mid-1990s. Some nurses who had worked at the Easneye nursery during the war came forward, but Tony was no closer to finding out about the circumstances of his birth.

"I had given up. I thought, 'No man can do more than I have done, so that's it,'" he says.

Then, four years ago, Tony joined a Facebook group for foundlings. They swapped stories about their lives and their theories about why they might have been left.

Tony thought he could be the result of a liaison between a British woman and an American GI. It's estimated that about 22,000 children were born in this way between 1942 and 1945.

"I was found in London and I know this is an area where it was happening," he says.

He mentioned his theory in the Facebook group, and it was a move that would change his life.

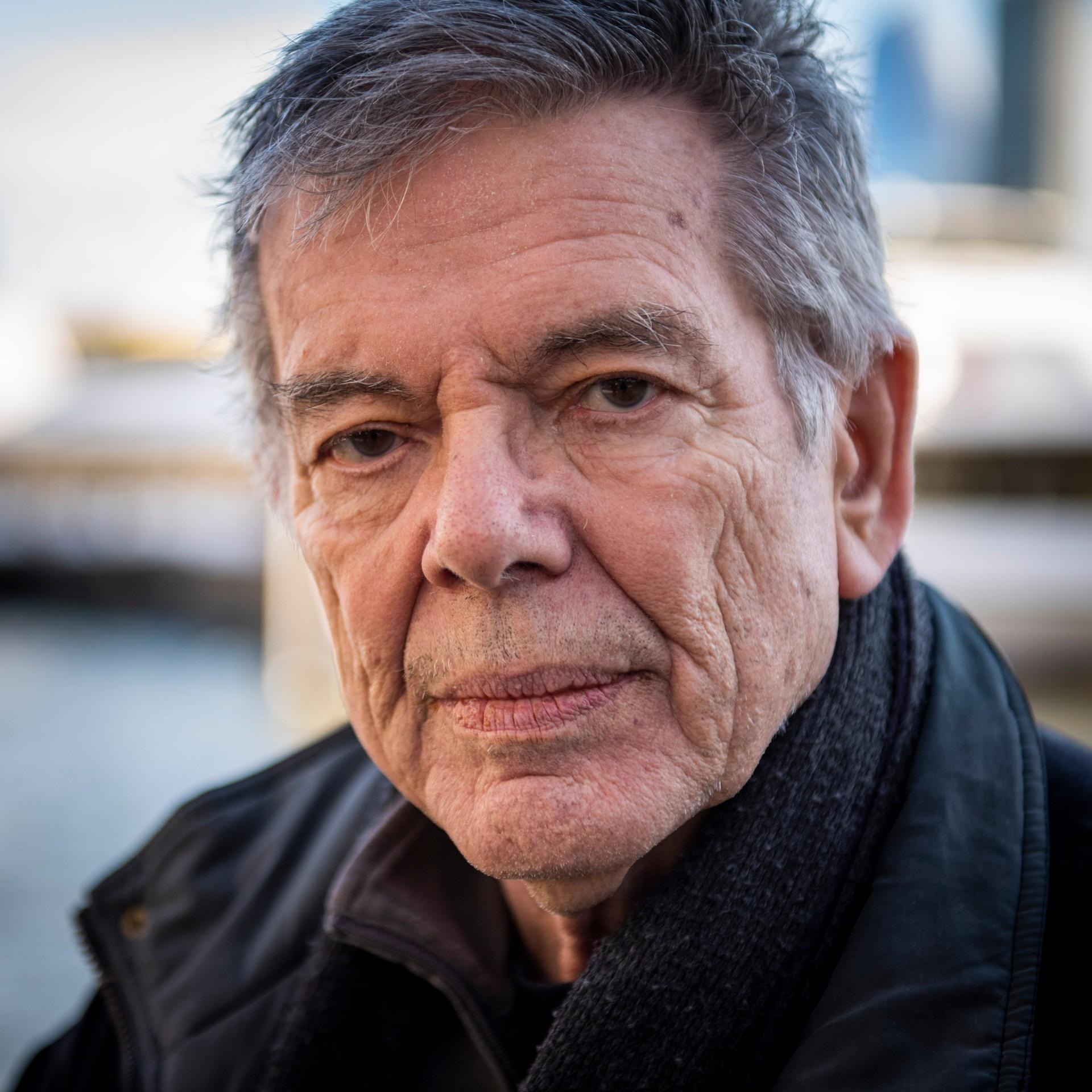

The post was spotted by Julia Bell, a genetic genealogist who has used DNA to track down American servicemen who fathered children during World War Two.

Julia's first successful case was working out who her own GI grandfather was.

DNA detective Julia Bell was looking for a new challenge

"My mother was over the moon to find out. Her father had died in 2009 but she had five brothers and sisters living all over the US. They send her presents for her birthday."

Julia was inspired by her experience to work on other GI cases, but she was now looking for a new challenge.

"I was finding the American servicemen cases very easy. They all knew who their mothers were, but not their fathers. I thought, 'How about giving that gift of knowing where you come from to people who don't know who either side was?'"

She had started looking at foundling cases when she came across Tony's Facebook post, so she introduced herself and offered to help free of charge.

"I thought, why not?" Tony says.

"I've tried everything you know, if you like you might as well go for it. I didn't think she'd be successful. How can you possibly be from so little information?"

And he was right that the case was a tough one, in fact it was the hardest that Julia had ever attempted to crack.

The first thing Julia did was search newspaper archives, where she found a small article from 20 December 1942 reporting Tony's discovery.

It read: "A blue-eyed boy four weeks old, wrapped in a bright blue jacket, part of a woman's costume, has been found abandoned on the Embankment."

Julia wondered whether this could be a sign that Tony was left in a hurry, and that perhaps it hadn't been planned.

She then turned to DNA, which she was convinced could help unravel Tony's case. It was 2016, and there had been a massive increase in the number of people in the US and the UK using DNA testing kits to research their family history.

Her first step was to send off a saliva sample from Tony to one of several privately owned companies that offer DNA matching with other clients on their database.

The amount of DNA we share with other people is measured in centimorgans. The number ranges from single digits for distant cousins to 3,400 centimorgans for a parent and child.

The test revealed a woman called Deborah in Toronto, who appeared to be about a third cousin of Tony's, judging from the amount of DNA they shared. But this promising link proved a dead end. Julia realised Deborah was most likely related to Tony on her father's side, and Deborah said she didn't know who her father was.

Listen to Embankment Baby, a BBC World Service documentary on BBC Sounds

After Deborah, Tony's closest relation was a fourth cousin called June, in Scotland. That meant she probably shared with Tony a pair of great-great-great-grandparents, who lived sometime in the 1800s.

"Now June had more of a complete tree, which she was willing to share with me," Julia says.

To find out which ancestor pair Tony and June shared, Julia searched the databases of the DNA-matching companies and found someone who was a cousin of both Tony and June at a similar distance.

"It's called triangulating," Julia explains.

"I found an ancestor pair living in the 1860s that all three people shared. Then I created a chart with all the different possible lines of descent, with every marriage and every birth.

"I looked for people further down the lines who were living descendants and asked them to do a DNA test. Each time I found a closer match that would help me refocus and refocus, getting closer to my goal."

By a closer match, Julia means a cousin closer to Tony in his family tree, sharing a larger amount of DNA.

The most common DNA test examines the pairs of chromosomes inherited from each parent (except the pair of sex chromosomes), but Julia also got Tony to do another test that looked at mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mother to child via the egg cell.

It suggested a strong maternal link to Lanarkshire, in the central lowlands of Scotland.

DNA testing

Every cell in your body contains DNA molecules, packaged in structures called chromosomes, which hold the instructions the body needs to develop, survive and reproduce.

The most common DNA test focuses on chromosomes from the cell nucleus, and particularly those inherited from both parents (22 "autosomal" chromosome pairs). The test matches you with anyone else on the database who shares a direct ancestor, reaching back about seven generations.

In men it is also possible to test the Y chromosome, which is passed from father to son and helps identify the paternal line.

The maternal line can be investigated by testing the DNA in mitochondria - subunits of a cell responsible for generating the cell's energy. This DNA is passed from mother to child in the egg cell.

It was slow and painstaking work but towards the end of 2018 Julia identified a couple she thought could be Tony's maternal grandparents, who had lived in Kirkcaldy, north of Edinburgh. They had a son still living in Scotland called Bill who was in his 90s and was reluctant to do a test. However Bill's daughter, Kathleen, agreed to help once she heard Tony's story. The results showed Kathleen was almost certainly his first cousin.

"So I'm thinking it's most likely that Tony's mother was Bill's sister," Julia says.

"Bill had a sister called Mary who died in 1988. Mary had had two children - a son, Peter, who had died in 2006, but also a daughter called Sheena, who was still living."

After thinking about it long and hard, Sheena agreed to meet Julia.

"Well this was back in January 2019," Sheena says, sitting across from me in her conservatory in Kettering, Northamptonshire.

"My cousin Kathleen had explained to me about Julia and this person who was looking for his parents. I thought whoever this Tony is deserves to know who his family is, but I didn't click at all what it had to do with me.

"She came here and told me, 'I'm 80% sure that your mum is Tony's mother.' Well you could have knocked me over with a feather, I knew nothing about it!

"I thought, 'How could my mum have done it?' And then I thought, 'What must she have been through to feel she had to do something like that?' If only she'd been able to talk to us."

Mary with Sheena's father

Sheena agreed to take the test and it confirmed Sheena was indeed Tony's half-sister. Julia went to Tony's house to tell him the news.

"When she came I had a friend with me, who was writing it all down. It was a hell of a lot to absorb," Tony says.

"It was strange, I felt much less happy than I thought I would do. It didn't have as huge an effect as I thought it would. But then I heard Sheena was willing to meet me, that was a big bonus."

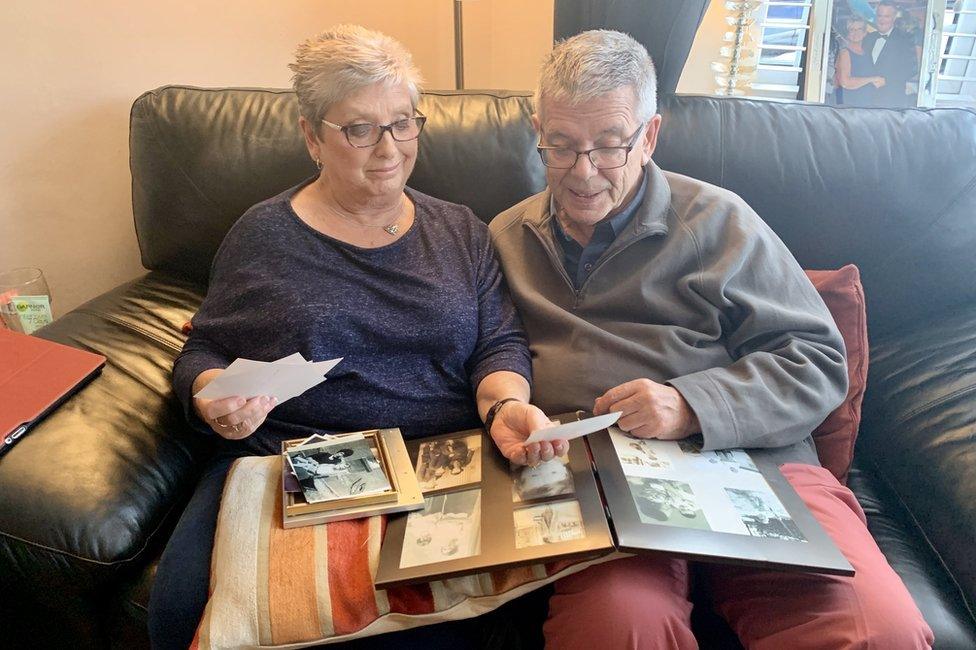

Sheena and her husband, George Haig, only live an hour's drive away from Tony and they agreed to meet him and Julia at a hotel.

"I just thought it was unbelievable. That I'm hugging the daughter of the woman who abandoned me and that she had been prepared to meet me," Tony says.

"Sheena gave me an album full of old photographs of the family. It was just lovely. She's a great girl."

Sheena, Tony, and the family photos

Sheena immediately noticed something familiar about Tony.

"He walked in and I thought: 'That's my mum walking towards me.' He was so much like her it was scary. I just couldn't take my eyes off him."

Over time, Sheena, 65, has helped Tony build a picture of their mother.

Mary married Sheena's father in 1946 and had two children. They moved to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, when Sheena was two. However, they came back to the UK after her father was injured in a car accident. He never left hospital and Mary raised Peter and Sheena alone.

Sheena as a young woman, and Mary

"She had a hard life but she was a loving person. She'd do anything for anybody," Sheena says.

"I've missed her more this year than I've done in a long time."

Meanwhile, Julia was still at work trying to find Tony's biological father. She discovered Mary had been married once before, which was a complete surprise to Sheena.

"Julia told us mum had married a man from Kirkcaldy called James on 1 August 1942, but she applied for a divorce in 1946," she says.

As Tony was born in late November or early December, Julia knew Mary would have been about five months pregnant at the time of the wedding. Although the DNA hadn't indicated a strong Scottish lineage on Tony's paternal side, Julia decided to follow up the lead.

She found out that James had gone on to remarry after his divorce from Mary and had had a daughter called Anita. When Anita was approached and told about Tony's story, her response took everyone by surprise.

"Her first words to us were along the lines of: 'Thank goodness he's fine,'" Julia says.

Anita says discovering the existence of Tony has laid to rest a family mystery that had troubled her for most of her life.

"I'd heard a whisper of a story but I was never sure it was true," she says.

"I was anything between eight and 10. I heard raised voices and I was listening at the door. I just heard, 'Oh, it's awful you know that a baby was left.' That would have been my mother speaking and my father was saying things like, 'You weren't there. It was dreadful, she was in a terrible state and she was going to jump off a bridge and I had to calm her down.'"

The young Mary Hunter

It's not clear if James knew Mary was pregnant when they got married, but Anita says her father insisted the baby wasn't his. Her understanding was that this led to some sort of argument between James and Mary in London. At the time, James was in the military and serving on the south coast. Perhaps Mary came down with the baby from Kirkcaldy to meet him?

"I suppose that's how the abandonment happened," Anita says.

"My father removed Madie [Mary] from the baby to calm her down and perhaps - I think I remember hearing my mum saying something like 'Did you never go back to see if it was still there?' And I remember him saying 'Of course I did, but obviously the baby wasn't there.'"

This is a second-hand account, told decades later, but it does suggest that both Mary and James were involved in leaving Tony on Victoria Embankment. An action that their children think profoundly affected both of them for the rest of their lives.

Mary had always told her daughter, Sheena, that her brother, Peter, had been a twin, but that the other baby had been stillborn. Sheena's cousin recently revealed she'd once asked their gran about the stillborn baby.

"My gran had been there at Peter's birth and apparently she said that was a load of rubbish, there was only one baby. So we now think that was my mum trying to make sense of it," Sheena says.

Mary with Sheena as a young girl

Anita said her father, James, was delighted when she had three girls and seemed uncomfortable around baby boys.

"He was a very supportive and helpful person. It just seems such an out-of-character thing for him and I think it weighed heavily on him," she says.

"In fact, in his late 70s he tried to take his own life and was treated for severe depression. I think the incident in 1942 with the baby [is something] he'd carried all those years and felt guilt and shame for. I think it contributed to his suicide attempt."

Both Sheena and Anita wish their parents could have known that Tony had been found and adopted.

Anita took a DNA test that confirmed what her father had always said, he was not Tony's father. So Julia's hunt continued, looking at DNA databases and creating numerous family trees using birth, marriage and death records. She narrowed down her search to two family lines based in Yorkshire and Hertfordshire. This meant he was unlikely to be a GI as Tony had first supposed.

Eric Wisbey emigrated to Australia

Then, just a few months after finding Tony's mother, Julia hit the jackpot with his father. She discovered a 1906 marriage that seemed to bring those two lines together. The marriage resulted in a son called Eric.

"I found this man called Eric Wisbey who looked to me to be the dad. I approached some living relatives who told me he had gone to Australia," Julia says.

"Eric had died in 2004 and he had a son called Ken who had died in 2011. But Ken had a daughter called Leesa and she agreed to do a DNA test."

Leesa lives in Wodonga, on the border of New South Wales and Victoria.

"I Googled Julia Bell's name to make sure that it wasn't a hoax," she says over Skype.

"You never know nowadays. And then I thought, 'Well, it's not going to hurt me.' So I agreed and she sent the test over."

The results came back a month later and confirmed Leesa was Tony's half-niece. This meant Julia was correct and Eric Wisbey was Tony's father.

How Julia did it

Starting in 2016, Julia Bell identified cousins of Tony on his mother's side, and used them to reconstruct part of his family tree, which led her to Mary, Tony's mother, and to Sheena, his living half-sister, whom Julia met in January 2019.

In her search for Tony's father, Julia established that Mary's first husband, James, had been present when Tony was abandoned, but was not his father.

Her attention then focused on two families in Yorkshire and Hertfordshire and a man called Eric Wisbey. When Eric's granddaughter, Leesa, did a DNA test in spring 2019, the result showed she was Tony's half-niece, and the case was closed.

Tony was amazed to discover he had family on the other side of the world.

"I have got a father that went out to Australia and now I've spoken to my father's granddaughter out there over the internet. These are huge bonuses," he says.

Leesa was able to tell Tony a little about his father.

"Eric was sort of a reserved fella, sometimes he'd take my brother, dad and I fishing," she says. He was a painter and decorator who moved around the state of Victoria. After his wife, Leesa's grandmother, died, he married one of her friends.

But how did Eric Wisbey, from the south of England, come to meet Mary Hunter from Scotland?

Leesa pulled out her grandfather's war records, which revealed he was in the Army Pay Corps in World War Two. In 1942 he was stationed in Edinburgh, 11 miles across the Firth of Forth from Mary's hometown of Kirkcaldy.

At the time Mary was 22 and living with her parents, while Eric was 35 and married with a young son back in Brighton. So how did this unlikely couple get together? Mary's brother, Bill - who has since died aged 93 - was asked if he could remember anything from that time.

"He remembered an older guy coming to stay at the house because he had to share a room with him," Sheena says.

"He was 15 years or so older than my mum and he said he thinks she'd had an affair with him. But he doesn't remember her being pregnant or a baby being born."

Sheena and George have speculated that Eric was billeted with the Hunter family, and was perhaps involved in paying the munition workers in the town. But did Eric ever find out that Mary was pregnant? Leesa reveals a tantalising clue.

"I had rung my mum to tell her about what was going on with Julia and then mum spoke to John, who was my dad's friend. And John said Dad had told him he thought he had a half-brother or had an inkling. I don't know how Dad got that information. I wish he was still alive so we could ask him about it."

Eric Wisbey left Scotland in 1943 after he moved from the Pays Corps to the Intelligence Corps. By 1944 he was stationed in India.

"He didn't really like speaking about the war and we never asked him about it. We found his records in a drawer," Leesa says.

Sheena thinks her mother was left in an impossible position.

"Whether he knew about it or not, Eric was married and quite a lot older than my mum. Then he went off to Australia. I think he got off scot free," she says.

"I feel angry and bitter that my mum felt she had to hide it all. What she must have gone through for the rest of her life, to my mind, is absolutely heart-breaking."

For Tony, the discoveries have helped him better understand why he was left on the Embankment. But he says he has never blamed his mother for leaving him.

"I wish I could tell her 'I'm sorry you had to do it,'" he says.

"I was sure she wouldn't have abandoned me without a damn good reason."

Dr Marilyn Crawshaw from the University of York has worked for decades with people who were adopted or conceived with donor sperm. She warns people to think carefully before embarking on a journey like Tony's.

"I very definitely believe a child has a right to know where they come from," she says.

"But I always say to people don't go rushing into it, stop and think first. Talk to your mates about it. Are you prepared for all the different things you might find out?

"Some bits might feel immensely satisfying, but you may also find a birth parent who refuses to have contact with you. You have no idea what is happening in the lives of the people you are approaching. You really are stepping into the unknown."

Tony says there are some things he will always wonder about, such as whether he was born in Scotland or London, but he is "happy to know what I now know".

His relationship with his half-sister has gone from strength to strength. Sheena and her husband, George, have met Tony's sister, Eleanor, while Tony has gone to watch his half-niece, Jessica, sing at a concert in London.

Tony is now looking forward to introducing Sheena and her family to his children and grandchildren.

"When Julia first told me she had a result I think I was a bit stunned," Tony says.

"But now I've met my half-sister, I've corresponded with my half-niece in Australia. I'm looking forward to introducing my son and daughter to Sheena's family. It's given me a new lease of life."

You may also be interested in:

After losing everything in the horror of Hurricane Katrina, artist Matjames Metson was broke, traumatised and "braced for the end" when he received an unexpected phone call. It was from the daughter he hadn't seen since she was a baby, and it gave him a reason to live.