‘Our foster child asked us to adopt him – by drawing himself on to a family photo’

- Published

George is one of tens of thousands of children in the UK who've been taken into care because their parents are unable to look after them. Severely neglected, he struggled to express himself, so when there was something very important he wanted to ask his foster family, he chose an unusual way of doing it.

George was three-and-a-half when he went to live with the Atkinsons. The moment he arrived, the children excitedly steered him into the living room to watch TV while their parents, Tony and Elsie, talked to the social worker in the kitchen. But George didn't seem to know any of the programmes that Nancy and Stanley were flicking through.

There was spaghetti Bolognese for tea, but when Tony and Elsie showed George his plate and his knife and fork he just stared at the floor. They pointed to tins of beans in the cupboards and frozen chips in the freezer in case he'd prefer something else, but George didn't seem to recognise any of it.

"We didn't know what to do," Tony says. "We couldn't engage him at all."

After dinner Tony and Elsie were at the sink doing the dishes when George suddenly moved from the spot where he'd been standing motionless for more than an hour. He ran to the fridge, took out a two-litre container of milk, bit off the plastic top and then the foil and drank the milk down, straight from the bottle.

"It went all over him - but at least we knew there had been milk where he'd lived," Tony says, "although he didn't seem to know about putting it in a cup."

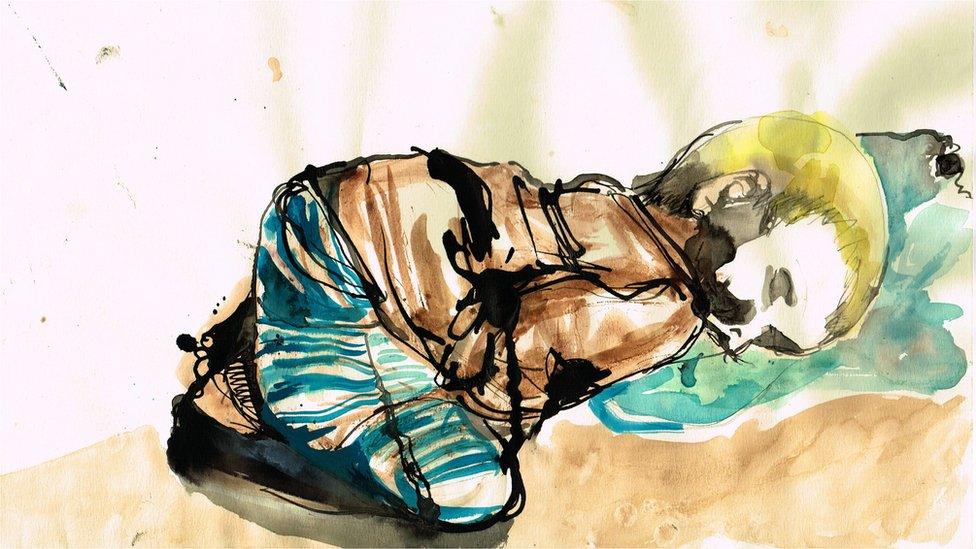

Later, when George seemed sleepy and Tony announced that it was bedtime, George fetched his coat and lay down underneath it on the living room floor. Tony gently ushered him upstairs to his new bedroom.

"He seemed unfamiliar with the concept of lying in a bed under a duvet," Tony says.

George was only the second child the Atkinsons had ever fostered. Before him there had been a baby who, Tony says, "didn't know to be scared". But George was altogether more complex - it was clear to Tony and Elsie that he'd been severely neglected by his birth parents before being taken away from them.

"George had obviously had a very, very difficult time," Tony says. "When he first came to us he was very pale - not a good colour - grey really. He had limited speech, didn't know that you sit at a table on a chair or what a spoon was for, and had no idea what a bath was.

"I don't think anybody had hurt him - they just didn't know how to look after him."

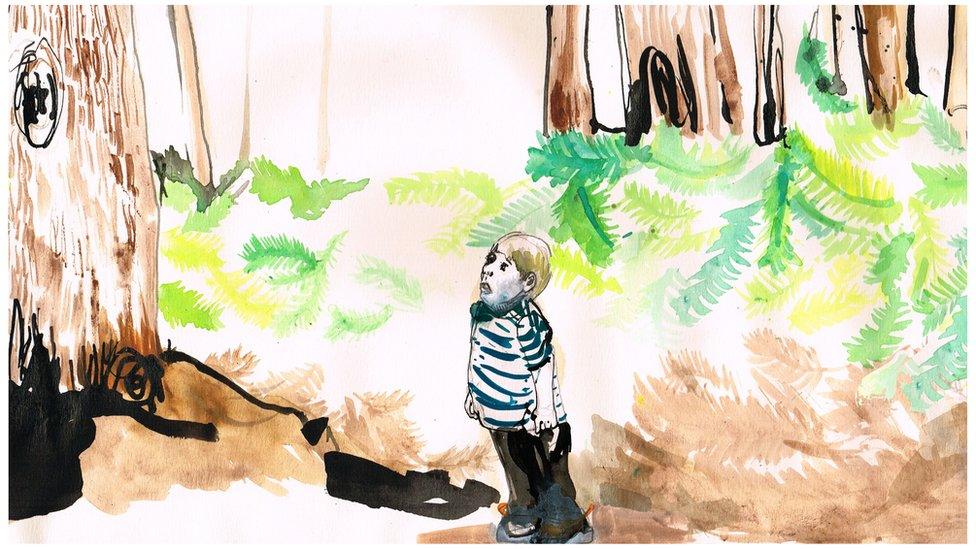

The next day Tony took George to the local park. He noticed George staring intently at something, and Tony realised that it was a tree. He took George over to the tree and together they looked at it and patted it for a good 20 minutes.

"This is the bark, and these are the leaves," Tony explained to George.

"This kid had never seen a tree before, and had certainly never touched one."

Tony and Elsie wrote down their observations and sent the notes to George's social worker.

"It gives them a picture of what this child has lived through, and basically confirms that he did need to be removed from his mum and dad," Tony says. "Because there's an awful lot of things that little kids should have been exposed to by the age of three-and-a-half that he hadn't."

George gradually settled into his new life with the Atkinsons and seemed to feel safe with them, Tony and Elsie thought. He began to speak and express opinions, and would get really excited when the microwave pinged to signal that his beans and sausages from a tin - his new favourite food - were ready.

But one day Tony discovered that George, who was now four, had drawn a circle with a dot in the middle on the walls of every room in the house, using a felt-tip pen.

"It looked like somebody had drawn boobs everywhere," Tony says. "Some parents would go ballistic, but as a foster parent, I thought, 'What's this all about?'"

"It's a force field," George told Tony as he pressed the little dot on the wall in the hall and went, "Beep!" and then walked into the living room and pressed the circle with a dot on the other side of the wall.

"Beep!"

"It keeps us safe," he added. Tony assumed George had seen something similar on TV.

"So I said, 'We do have a front door and that keeps us safe too,'" Tony says.

"And George looked at me and he said, 'Not always. Doors don't always keep you safe.'"

To help George feel more secure, Tony bought a cheap, traditional doorbell from the supermarket, hid it in the front garden and told George that if he pressed the special button a security screen would envelop their whole house. George could press the button whenever they went out and then press it again when they returned.

"We only had to do it for a few days, and then I painted over the circles with the dots," Tony says.

"The kid was scared and there were reasons for that that I didn't understand, but they were real and I needed to make him feel safe."

During the 16 months the Atkinsons were fostering George, a court case ruled that his birth parents were unable to look after him and he would never be able to go back to live with them. George's mother and father were granted one final contact with their son, who was now about four-and-a-half.

"And that was the last hour they would ever have with him," Tony says. "That's it forever if your child is permanently removed - unless they want to find you when they're older."

There weren't any other relatives who could take George in, and Tony and Elsie wondered what the future held.

"People just don't want to adopt children when they are four or five or six - particularly if they've got medical, emotional and all the other issues going on," Tony says.

But against the odds, just before he turned five, George was matched with a couple who were desperate to adopt. They sent him a photo-book of pictures with captions that read, "I'm going to be your Daddy", "I'm going to be your Mummy", "This is going to be your new house" and "This is going to be your garden".

"And then there was the realisation that as a foster carer there's going to be a significant amount of grieving," Tony says, "because you're going to have to hand over the child."

The adoptive family came to visit. Elsie, Nancy and Stanley went out, and Tony made himself scarce upstairs while George and his new parents played on the living room carpet and tried to bond.

On the second day, the new family took George to the park, and on the third he visited their house. The transition rolled on gently for a couple of weeks, and things were going really well - George was a bit unsure, but mainly excited. Then one Tuesday morning the social worker collected George to take him to live with his new family and told the Atkinsons that this was goodbye.

"The social worker shut the door and they got in the car, and then we all burst into tears," Tony says.

"Sometimes people say to me, 'I could never foster because I'd be too upset when they go,' but the tears you shed are the price for that child to have a forever home - and that's a price you're prepared to pay."

The Atkinsons stayed in touch with George's adoptive family for a while, but Tony and Elsie knew they couldn't keep visiting because George needed to bond with his new parents, so when contact gradually dwindled it felt natural - Tony and Elsie assumed everything was still going well.

But 20 months after George had left them to live with his "forever family" there was unexpected news.

"We got a phone call saying, 'Do you remember that little boy? You're the only people in the world that he has any connection with. Could you take him back?' The adoption had broken down," Tony says.

"Adoptions sometimes break down in the first two or three months - but for an adoption to break down after that length of time is quite unusual."

By now George was almost seven, and Tony and Elsie knew that if they took him back it wasn't going to be easy.

"Because we were going to get a very angry, very troubled little kid back," Tony says.

After much consideration the Atkinsons decided that they would foster George again. On the day that he returned he ran up to his old bedroom and put his things everywhere, and then placed his small collection of DVDs next to the TV in the living room. He slotted back in pretty well, but Tony and Elsie worried about how the breakdown of his adoption was going to affect him.

"That sense of 'my birth parents didn't love me enough to keep me, you as foster carers didn't keep me, then my adopted family rejected me - I am unlovable, and so I will push everybody away to prove that,'" Tony says. "Many kids in care have a similar attitude."

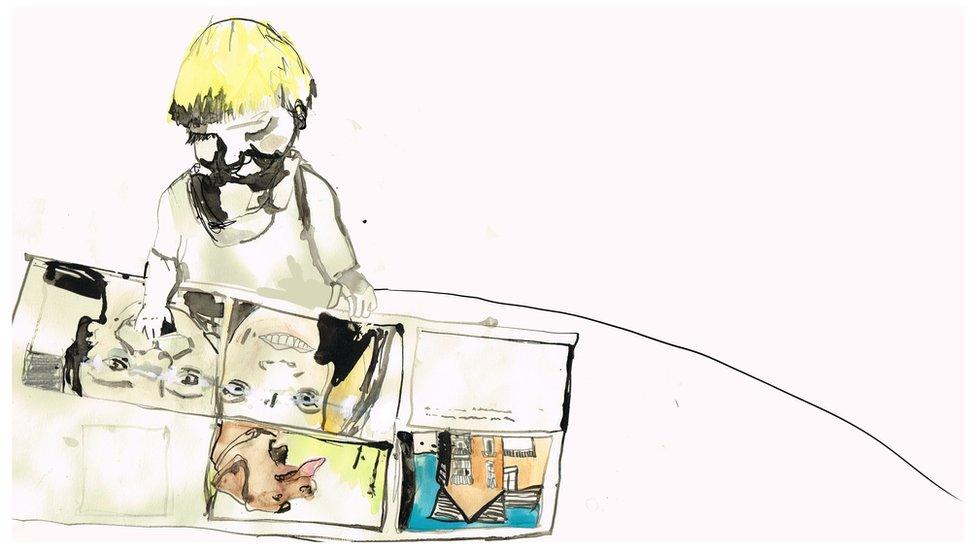

About two years passed and although having George back hadn't been entirely plain sailing, things were going pretty well. Then one day Tony realised that George had been "ominously quiet" and went to see what he was doing.

He found George sitting on the living room floor surrounded by shards of broken glass. A framed photo of Tony and Elsie and their two birth children, taken years previously - long before George had arrived in their lives - lay in pieces. George had broken the frame and prised it apart. He'd taken the photo out and, with a marker pen, drawn a stick figure of a small child with the most enormous smile - himself - standing behind Nancy and next to Elsie.

"It makes me really emotional even now to think about it," says Tony, who now regards this picture as a family treasure - the thing he'd want to save if their home was burning down.

"George wasn't necessarily the most articulate kid in the world, but it was obvious that this was his way of communicating something that was quite hard for him. To say, 'I want to be in your family,' is a massively vulnerable thing to do when you're eight and you haven't got any other options. You're really putting your heart out there."

Tony told George what a lovely picture he'd made and asked if he'd like to become an Atkinson.

"He just nodded," Tony says. "He's circumspect with his emotions because he's been hurt so many times, and by now he knows adoptions don't necessarily last forever, they're not necessarily happy endings."

Fostering and adoption

There are 78,150 children in care in England, but there is a national shortage of carers who can give them a home, care and protection.

Fosterline, external is a free, confidential, impartial advice service for foster carers and those thinking about becoming foster carers.

Tony and Elsie talked to George's social workers about beginning the long process of applying to adopt.

"Fostering is temporary, even if it lasts two years," Tony says. "With adoption you are taking on the child entirely - as if they're your own - and you're taking on all the responsibility - financial, relational, emotional. You're basically saying, 'You will be in our family like a birth child, so your children will be my grandchildren, and your grandchildren will be my great grandchildren.' It's a big, big thing to do."

Four years ago, at the age of nine, George finally became an Atkinson. But Tony says that changing his surname and telling him he'd been adopted wasn't an instant fix for the deep-rooted problems that began when his parents proved unable to raise him safely.

"To undo that damage takes a tremendous amount of time, of being there for them," he says.

"They will be very difficult and they will push, push, push you to try and make you snap and go, 'You're right! You are horrible, I never want to see you again.' And then they can go, 'I knew it! I knew I was unlovable.' So what you have to do as a foster carer or adoptive parent is just take that anger and meet the needs of the kid."

Since being adopted, George has gone through what Tony describes as a "period of regression", during which he "fathered" and "mothered" a toy baby for about three months.

"One of those realistic ones," Tony says.

George talked to the baby - who he named John - washed him, clothed him and took him out for walks, while Tony and Elsie supplied baby John with real clothes, a real buggy, nappies and a cot.

"For George, John was as real as you and me," Tony says. "George was basically re-enacting everything he had missed out on, it was beautiful to watch. Then, one day, John got shoved under the bed and forgotten about."

Other moments have been more challenging, such as when George announced that he urgently needed an expensive smartphone in the middle of the night.

"There's no way you can get a seven-year-old an iPhone X at two in the morning, even if you did think it was a good idea," Tony says.

But George was adamant, so Tony suggested they go to see whether the local pawnbroker shop had any for sale.

"With a birth kid you'd never do this. You'd say, 'Be quiet and go to bed!' But with a foster kid you have to think about trying to meet their needs," Tony says.

"So we walked up the road, taking the longest route possible to gradually calm him down, and when we got to the Cash Converter, lo and behold, the shutters are down because it's two in the morning. So I said, 'I've got another idea! When we get home we'll get cardboard out of the recycling bin, print out a photo of an iPhone X and we'll stick it all together.'"

George agreed to Tony's plan and after they'd walked the 20 minutes home, they made their cardboard smartphone from the empty containers among their recycling.

"We went to bed about four in the morning, absolutely exhausted and your patience is tested," Tony says. "But by meeting those needs you're gradually forming a bond of trust where this kid goes, 'I believe you when you say you will look after me, I believe you when you say I will never be hungry again, I will never be neglected again, I will never be left alone again, I believe you when you say you love me.'"

George turned 13 this year and although he used to find birthdays really difficult - he'd destroy any gifts that people gave him because of his belief that he was unlovable - this one was the best birthday he's ever had, despite it falling during the Covid-19 lockdown.

"Now he gets really excited about presents," Tony says. "But on his birthday, he will still sometimes say, 'I wonder what my birth parents are thinking today?'"

Recently he had a question for Tony - who he usually calls 'Dad' at home and 'Tony' when they're out.

"He said to me, 'When I'm older, when I have kids, what will they call you? Will they call you Tony or will they call you Granddad?'" Tony says.

"He's looking forward to the future, he's thinking, 'I'll still be here' - and that's really beautiful," he adds.

It's seven years since George came back to the Atkinsons and coming up on a decade since he was first fostered by them. And things are going well, despite the start in life George had.

Tony wonders whether George's parents were themselves neglected as children - maybe this would explain why they didn't know how to bring up their child? "But hopefully, if George has children," he says, "they'll never have to experience what he's experienced."

All names have been changed.

Illustrated by Katie Horwich

You may also be interested in:

When a mother has a child taken from her by the courts and social services the chances are that her next baby will be removed as well - in the baby's own interests. But social workers may give the mother and her partner a chance to show that the new child will be safe in their hands.