Smash and Angel Delight: 'The mixer that helped my family through hard times'

- Published

An ageing mixer reminds the writer Rebecca Stott of a period of adversity for her family in the 1970s, and the way her mother gritted her teeth and got them through it. Will today's children one day look back at the difficulties of the Covid era, she wonders, and remember someone who did the same?

A few weeks ago my mother, now 86, announced that it was time to let the Kenwood Mixer go. She couldn't remember the last time she'd used it, she said. Nor could I. She had tried to get it out of the cupboard, she told me, but it was too heavy for her to move now, with the arthritis in her hands and back. I wrestled it out and up on to the sideboard. There it was: our 1962 701-model Kenwood Major, navy blue and white, rusty at the base, its stainless-steel bowl a little dented in places but still gleaming, still ready for action. She and I stood side-by-side in the tiny family kitchen looking at it in silence for a while. Then she said: "I don't know how we managed." Just that: "I don't know how we managed."

Back in 1976 our family ran into trouble. My father walked out, leaving my mother with five children to raise and no job. I was 12 in 1976, my brothers 13 and 10. The twins were five. We'd had ten years of relative affluence as a family by then - nice cars, good clothes, holidays, two of my brothers had started at private schools - but now we were up to our eyes in debt. My father had got himself caught in the talons of a gambling addiction. My mother knew about some of my father's debts when he left that day in 1976, but she wouldn't see the full extraordinary scale of it until he ended up in prison for forgery and embezzlement five years later.

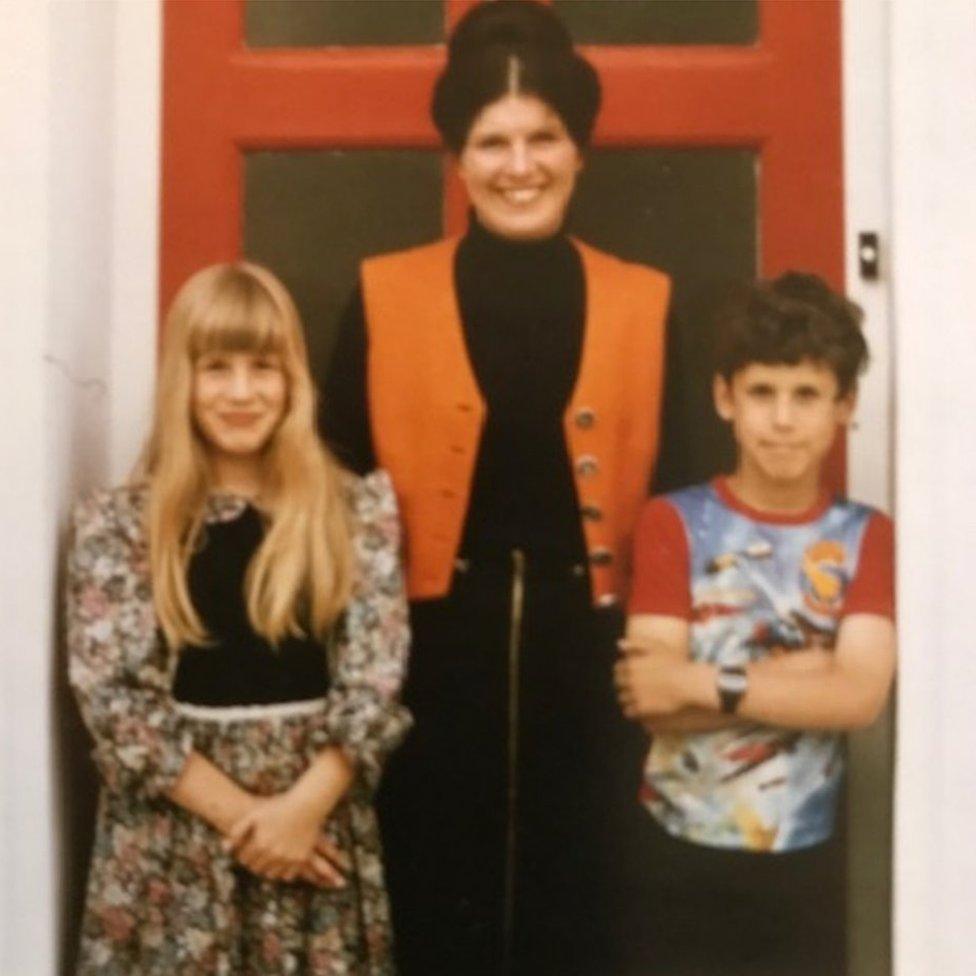

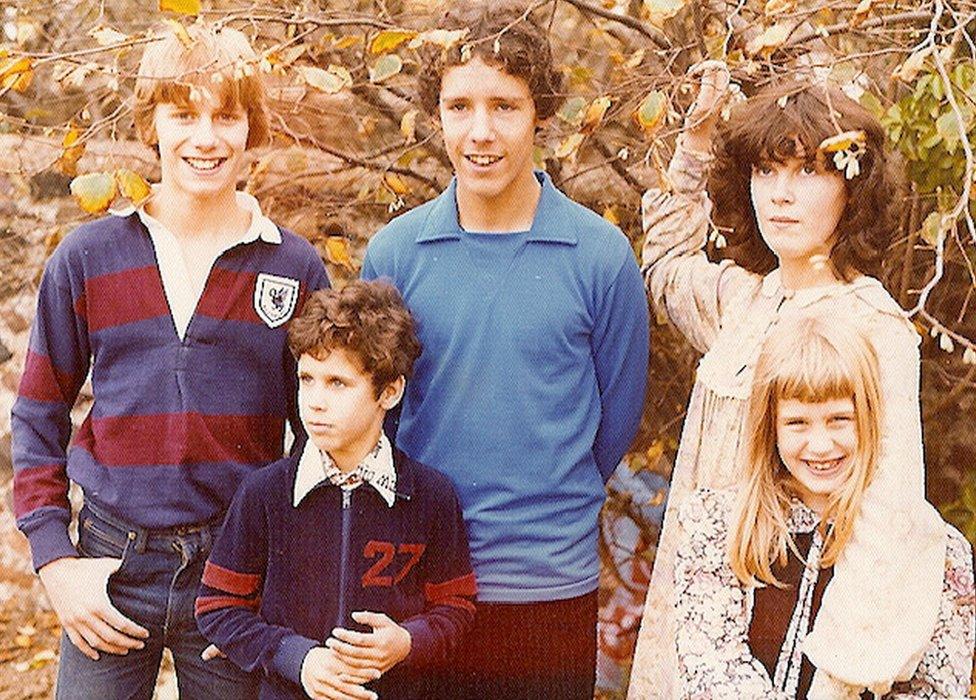

Rebecca Stott aged 14, outside the house in Hove

My mother did the maths and made a plan. Within weeks she'd sold the too-expensive family home and bought a terraced house near the sea in Hove, just big enough for her to take in three paying language students. We children took the two attic rooms, girls in one side, boys in the other. The language students, young people from all over Europe, took the others. Knowing that the income from the students wasn't going to be enough to keep us all fed and my brothers at their schools, she took on three part-time jobs in accountancy and book-keeping as well.

There were breathtaking logistical problems in this plan of hers. Working away from home nine to five and often on the road, she also had to cook a supper for nine people seven days a week, change sheets and towels for each new guest arrival and make sure we were safe and keeping up with our schoolwork. She didn't get home from work until after 5pm. Dinner had to be on the table at 6pm. There were no relatives or friends to step in, and she'd have been too proud and private or just too busy to ask for help anyway, so at 12 years old I became my mother's enthusiastic helper. And this is where the Kenwood mixer came into its own.

Rebecca Stott's mother, and the twins

The secret of feeding a large household with no time on a really tight budget, she taught me, was convenience food purchased in industrial quantities from the local Cash and Carry. It was mostly powdered. And thankfully there was plenty of powdered convenience food available in the late 1970s. I'd get home from school half an hour before her and get the oven on and deal with any impromptu visits from the bailiffs who'd turn up from time to time looking for my father. Usually there was a meal plan on the sideboard. Sometimes there wasn't. Some nights I'd have to improvise.

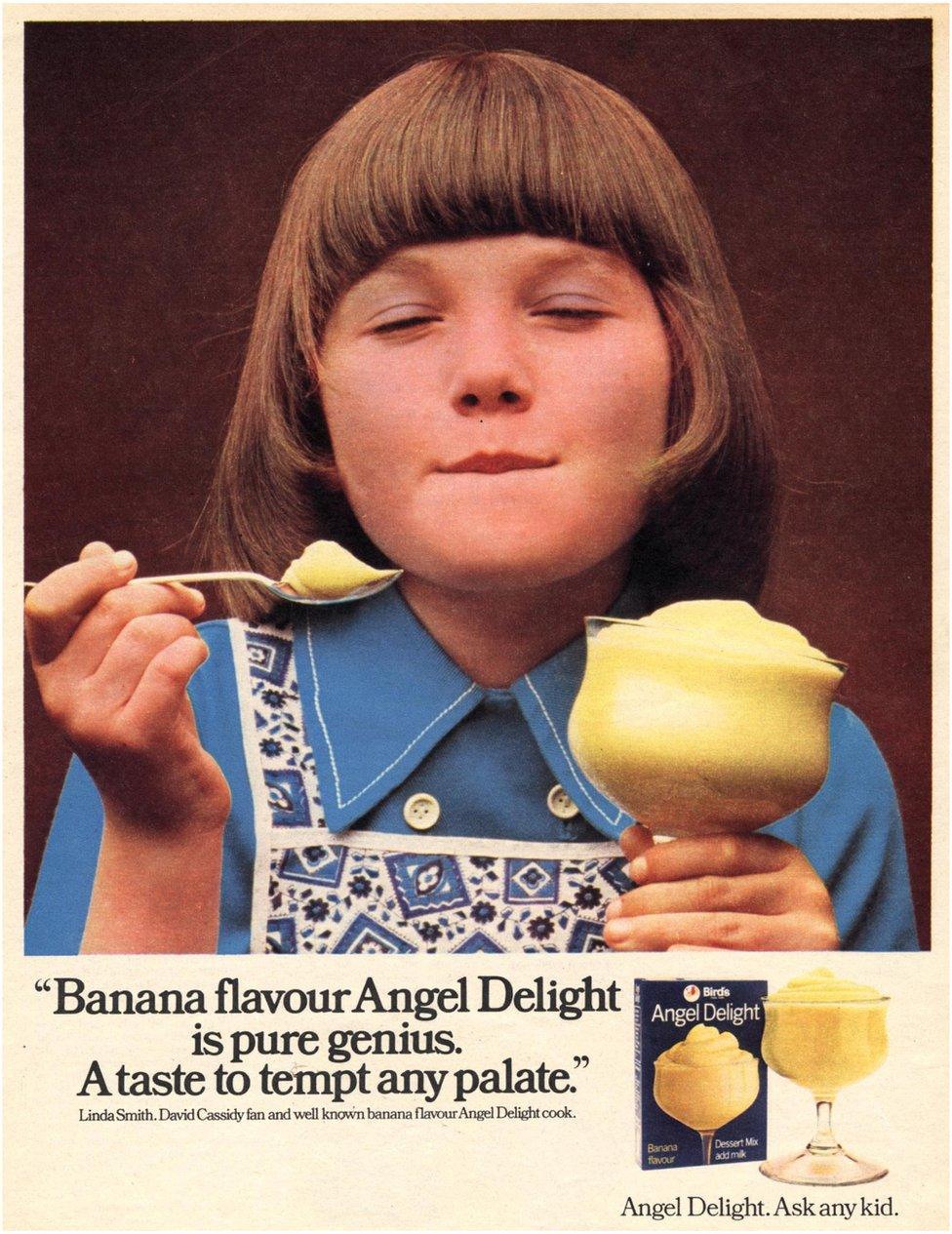

Every night we'd pour cups of Smash powdered potato into the stainless-steel bowl of the Kenwood and add boiling water straight from the kettle. Sometimes there was butter to mix in, usually margarine from a huge tub. We used the ice-cream scoop to make mounds on a baking tray, piled on some grated cheese and grilled them. At least once a week we made what my mother called concoctions: these were layers of leftovers, made in two huge pyrex dishes, sometimes interlayered with a catering tin of baked beans, the whole lot topped with more Smash, some grated cheese and shoved in the oven. Occasionally we made spam fritters, on birthdays and other special occasions spaghetti bolognese. For pudding there'd be Angel Delight mixed up and refrigerated the night before, or some kind of jelly with tinned fruit, occasionally a sponge mix poured over tinned peaches.

Powdered foods were popular in the 1970s

None of the food we cooked bore much relation to the glamorous, manicured technicolour food in the Kenwood manual. And we certainly didn't look very much like the well-groomed smiling mothers and daughters in those pages either. And of course I wasn't always a compliant, helpful daughter. Teenage roaming with my friends in Brighton after school, or hanging out on the pier, or in their houses listening to Bowie or Neil Young, became a new kind of sweetness. I'd give my mother excuses at first, and then later, plenty of "lip", as she'd call it. But, for a while at least, my mother, the Kenwood and I were in it together.

I don't think I ever heard my mother say "Keep calm and carry on" but she had plenty of similar phrases, like "Don't make a palaver," or "Where's your backbone?", "Buck up," and "Put some welly into it." She'd most likely learnt those phrases from the women who raised her: my grandmother, who had got herself up at dawn every day to blacken the grate, turn the mangle, beat the carpets, bake and polish through the war years, and from Auntie Nelly who had been the housekeeper at the local manor house.

I have never had a professional training course since those years, not in time management or people management or in leadership, that taught me as much as the apprenticeship my mother gave me in the late 1970s.

So now I am driving up the A23 back from Brighton to my home in Norwich, the 701-model Kenwood Major, first produced in 1962, strapped into the passenger seat. The K beater, the whisk and the dough hook are rattling around in the bowl, and I am tasting butterscotch Angel Delight on my lips. The sweet powder always clouded the air over the bowl before the milk released its lurid colours.

And I'm thinking: "Well those years weren't so bad." Once dinner was ready, I'd ring the little bell she'd rigged up in the hall. Now I can hear my siblings and the foreign students thundering down the stairs, just as they used to do. I can see my mother passing round the plates asking the questions she'd ask our guests most nights: "What did you see from the bus today?" or "What did they teach you at school today?" My little sister is rolling her eyes. "They're supposed to have daily conversation practice," I can hear my mother hiss. "So give them conversation practice." Most nights we put on a good show.

And it wasn't always a grind either. On Sundays she'd bundle us all in the car for an outing to keep our spirits up, and presumably also her own. We'd play the Left-Right game, a game she'd made up. At each crossroad, each of us took a turn to decide whether to turn Left or Right. We could also choose to stop and get out sometimes. That game taught us all that taking a chance, abandoning the plan, would sometimes yield unexpected pleasures. I remember a forest thick with pine cones, following a path through a field of poppies and finding an abandoned railway station littered with the sodden pages of pornographic magazines. She did not allow us to linger for long there.

Rebecca Stott (back right) with her siblings in 1979

I never saw my mother curse or cry or throw anything, but her teeth were often gritted. I'd sometimes find her at the kitchen table late at night hunched over piles of bills or making her way through another section of the endless mending pile. If she was angry at her lot, she had learnt not to show it. I'm thinking now of that striking confession that Marmee makes in Little Women: "I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo; I have learned not to show it and I still hope not to feel it, though it might take me another 40 years to do so." Some days my mother just let the hoover or the Kenwood do her roaring for her.

When we all look back together at the chaos and worry of these Covid days, when we ask, "How did we manage?" - living in the grip of worry about jobs, futures, the health of our old people, exams, home-schooling, paying the bills - my guess is that we'll all remember someone who gritted their teeth, made a plan, and managed.

You may also be interested in:

When her oldest daughter left home, Audie had to go part-time in order to be there for her two younger children after school. Previously, she'd made ends meet by working long and unsociable hours. Now she was sinking into debt - and at first there didn't appear to be a solution.

'Until I met my debt mentor, I couldn't always feed my kids'