A child of 9/11 who won't be pressured to vote

- Published

Natalia Jones-Pinkney was a school pupil in the class that US President George W Bush was visiting when he was told of the 9/11 attacks. The media descended on her community - but much of what they reported was at odds with what Natalia had seen for herself. The experience shaped the way she views the current election.

For weeks, her family had been reminding her that she would remember this day for the rest of her life. On this particular Tuesday morning, in Sarasota Florida, seven-year-old Natalia Jones-Pinkney's mother, Stephanie, woke her up earlier than usual, to put extra tight half-braids in her hair.

"Remember what we talked about," she said as she smoothed out Natalia's crisp white shirt and grey shorts. "You're going to keep it down and be on your best behaviour. The world is going to see you today."

The girl nodded. It was a valuable reminder. Natalia knew that she had a theatrical streak. When she played in the road, she told anyone who'd listen that she was going to be famous one day, that she would make millions, and she'd help her whole family. But that outgoing persona had to be contained every now and then, her mother would tell her, especially on a day like this Tuesday.

As they approached the grounds of Emma E. Booker Elementary school, only a short walk away, Natalia was in awe of the scene.

"There were limousines everywhere. There were police on horses," she says. "I thought 'Oh my God!' There were men in suits and sunglasses, the secret service, it was like a scene out of Men in Black. And there were so many white people."

School was an extension of home for Natalia. Her aunt Josephine worked in the cafeteria there, and it was less than a minute's walk. This was the first time Natalia had seen so many unfamiliar faces in the area.

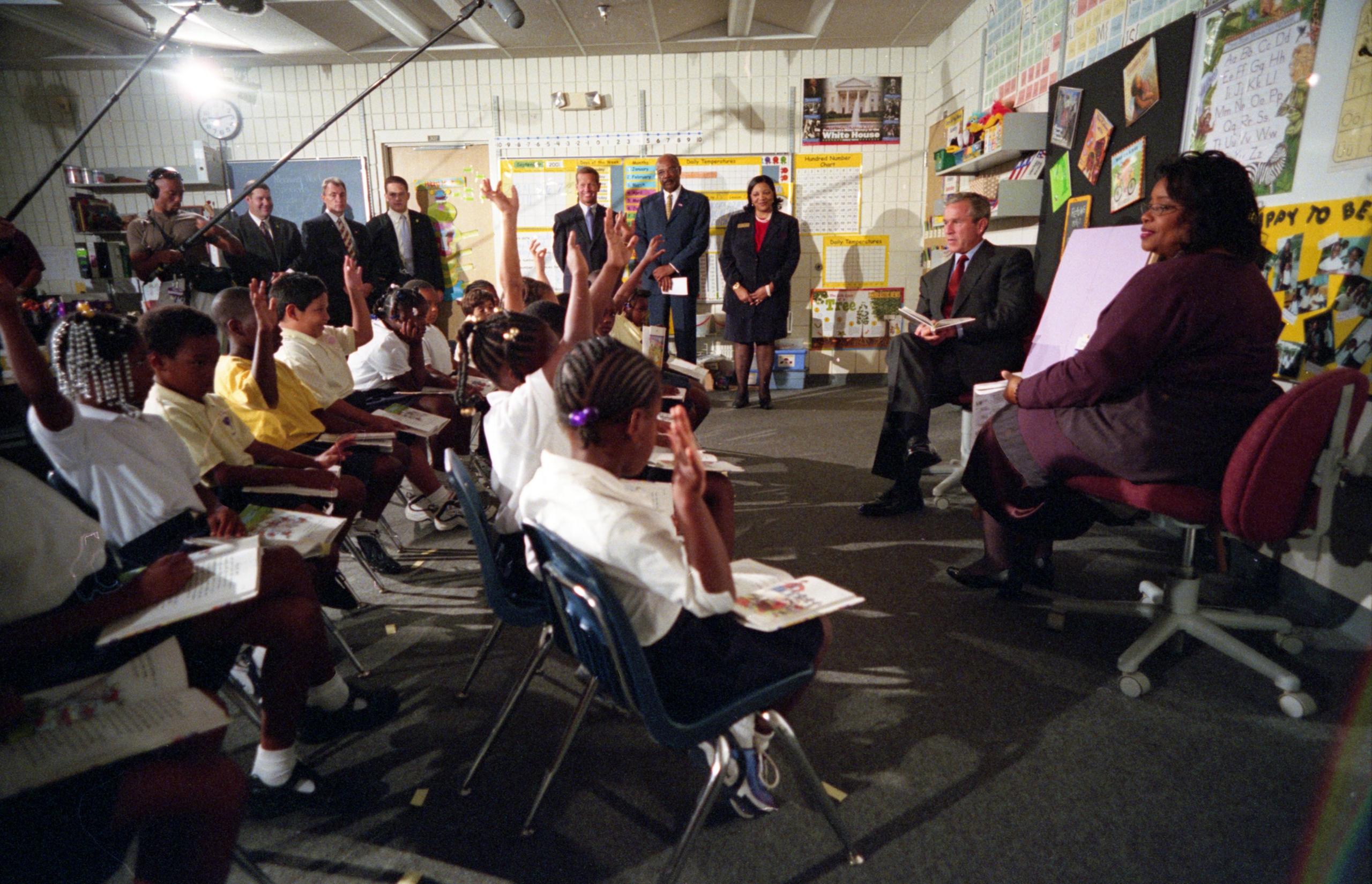

Ushered through a metal detector, Natalia was taken to a classroom where rows of chairs were positioned facing the whiteboards. These were for her and 15 of her second grade classmates. She took a seat on the edge of the row. Behind her were several adults, all in suits, whom she didn't recognise - and many stood next to cameras, all pointed toward her and her friends.

"And then Mrs Daniels walked in and I was… 'Wow!'" Natalia laughs. "She always looked pretty but today, wow, she looked beautiful. Beautiful."

Kay Daniels in 2002 - remembering the events of 9/11 one year on

Kay Daniels, had her hair freshly curled, and more makeup than usual. She had been Natalia's teacher since she started school and she was a firm favourite of the class.

"Mrs Daniels made an effort with everyone to make sure they learned. She taught on your level," Natalia says.

On seeing familiar faces again, Natalia relaxed. The children fell into easy chatter with each other, giggling at how smart each of them looked. All their parents had taken extra care.

Just before 09:00, the room fell silent as the children were instructed to stand up to welcome a special guest.

President George W Bush walked into the classroom. As cameras clicked at the back of the room, he stopped in front of Natalia to shake her hand.

"I was not expecting this," she says.

Smiling at the children, he moved to the front of the class where he took a seat opposite Kay Daniels, who then began a lesson with the class, which included reading from a book called The Pet Goat.

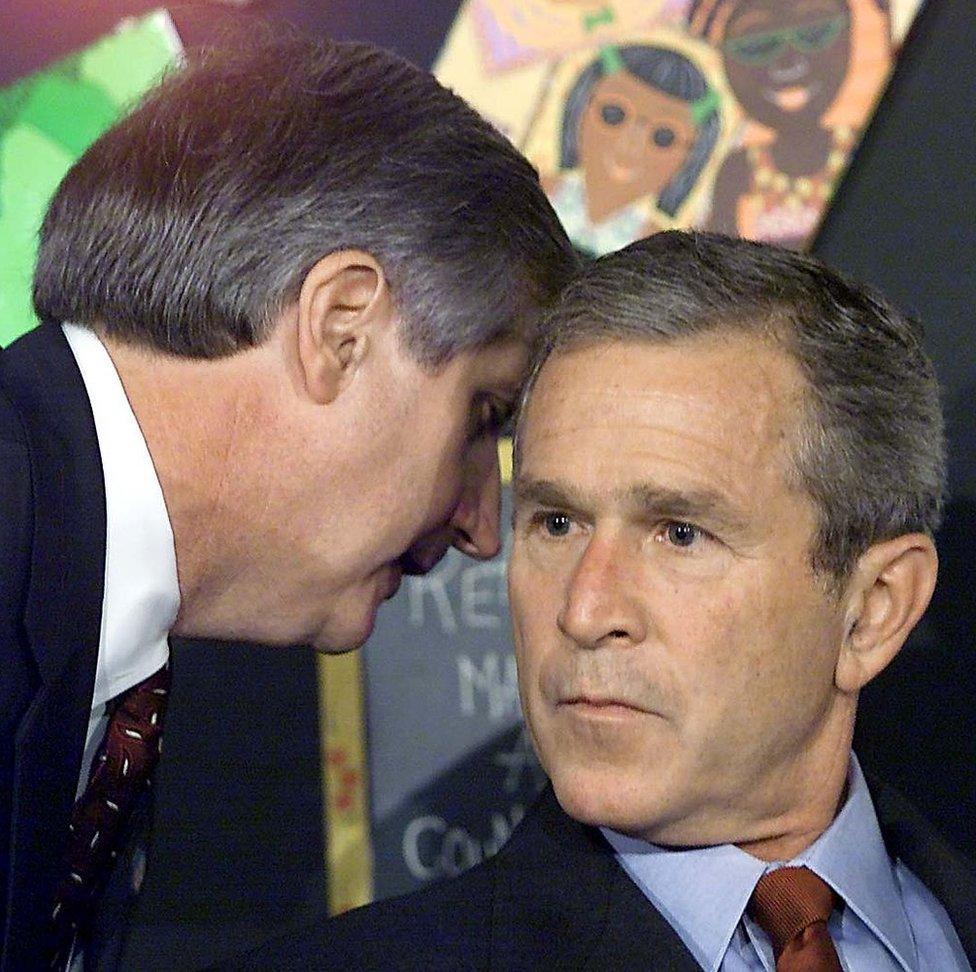

A few minutes into the class, Andrew Card, the White House chief of staff walked up to the president and bent down to whisper something into his ear.

"After that moment, the president just checked out," says Natalia. "He was gone. He mentally just left the room, he turned bright red. We thought he may have needed to pee real bad."

Andy Card whispers in George Bush's ear

What Natalia didn't see was that White House press secretary Ari Fleischer had positioned himself behind her, holding a card towards the president, with a message written on it: "Don't Say Anything Yet."

For the next seven minutes the president sat in the room, before he praised the children for their reading skills and excused himself to leave, ahead of the scheduled time.

Moments later the class would learn why. And years after that, Natalia would see herself in news reports and documentaries, on the edge of the frame, just before Andy Card bent down to George W Bush and whispered: "A second plane has hit the second tower. America is under attack."

Newtown isn't mentioned in tourist sites or glossy travel brochures. In 2019, according to the Visit Sarasota website, the city had more than 2.7 million tourists from around the world coming to enjoy its white sand Gulf Coast beaches. But head directly north for around two miles, past the city's business centre, and you'll reach Newtown, where Natalia was born. It's different there.

"It's the 'black area'," she says. "It is about 10 blocks that are entirely black, almost 100%, and it's very different to the rest of Sarasota, which is wealthy - it has golf clubs and country clubs. That's the white area. It's separate."

Natalia was born into a large and loving family and brought up by her biological mother's sister, who was unable to have children of her own.

Natalia was born and raised in Sarasota, Florida

"I had two mothers," says Natalia. "And lots of aunts and uncles, two sisters and a brother and many cousins. We were in and out of each other's houses and it was a great childhood. And our teachers were like extra aunties and uncles."

Emma E. Booker school was a central part of the community. It had been named after one of the first African American teachers in Sarasota, who was determined to ensure black children had a good environment in which to learn. In 2001, children at the elementary school were overperforming in the state in terms of literacy, and this had been flagged up to the politicians in Washington.

To promote his administration's recent promise to ensure education was equally available to America's diverse communities, George W Bush had then arranged to visit, and 16 pupils with good reading skills were chosen to meet him.

The president walked in minutes after hearing that a plane had crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. He was seated opposite Mrs Daniels and facing the children, when the second plane hit the south tower at 09:03. Two minutes later that information was relayed to the president, and after remaining in his seat for a while as the children read, he got up to leave.

President Bush confers with White House staff in another room at Emma E. Booker school

"I thought, 'What happened? Did I do something wrong, did I say something wrong?'" Kay Daniels says.

"It got strange after that," Natalia says.

"Someone bought a TV into the room and put on the news and that's when we saw what had happened.

"As a kid watching the buildings on fire, watching people jumping out of buildings, screaming, yelling, it was traumatising. Most of us began to cry."

Mrs Daniels switched the TV off, turned to the children and began to sing a gospel song, Hold On, Change is Coming. It would be a song the students would sing together many times while they remained at the school.

News programmes all over the globe picked up the statements President Bush gave in the cafeteria of the school less than half an hour later, addressing what he knew about the largest foreign attacks on American soil. He left soon after, and with him went the cameras, horses and men in black.

One by one the parents of the children arrived to take them home, the teachers soon followed and by noon the school was empty.

In the weeks that followed, Natalia felt more eyes on her. While she played with her friends or siblings, she could see adults in the area, be it an auntie or a neighbour, regularly taking turns to step outside to look out for the children.

"The media made out that America was now a place where people were angry and scared but I saw people in Newtown come together and look out for each other more. I felt taken care of," she says.

The 16 children reunited for a group photo in 2002 - Natalia is third from left in the front row

There were camera crews around the neighbourhood, and local and international media asked the children to speak about their experiences. Natalia and the others who were in the room that day bonded as they visited news stations and met reporters.

"We did interview after interview after interview," she says. "They were all asking the same questions: 'What was the president thinking?' 'What was the president saying?' 'How did the president look?' We didn't say much, we were kids."

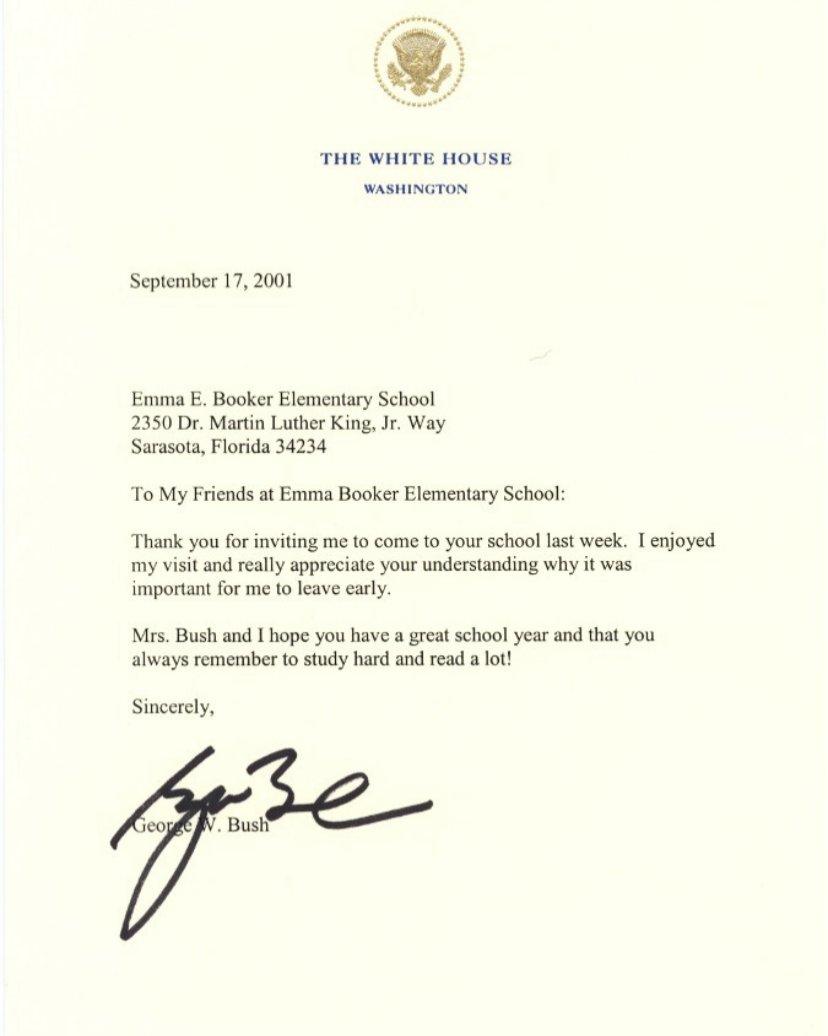

Years later, Natalia read accounts of the day that didn't tally with what she had seen with her own eyes.

She read articles that said the president remained calmly reading from The Pet Goat after the terror attack. In fact, he didn't read to the children at all.

"If they could get that detail wrong, when there were so many cameras present, what else could they get wrong?"

A letter from President Bush to Booker apologising for cutting his visit short

She also took issue with those who criticised the president for his behaviour that day.

"It wasn't fair to say he was just casually sitting there doing nothing while America was under attack," she says. He left as soon as he could without causing the children to worry, she says.

And she disliked the way the children were sometimes described just as "inner-city kids", which felt reductive, or how it was assumed they came from troubled backgrounds and couldn't possibly succeed in life.

The group of children stayed close all through primary and middle school, and in a happy turn of events, Mrs Daniels remained their teacher and taught them several years after second grade. But by high school the group began to drift apart, and were only recently all reunited when a documentary crew asked them to appear in 9/11 Kids, a film about where they all are now.

"The children in that classroom represent all of America," says Elizabeth St. Philip, the director.

"There is no one singular story there. One joined the military, inspired by the events of that day, one earns six figures as a business consultant, another is sadly in jail.

"This is a unique generation. They watched people die on TV at primary school and came of age through the rise of social media, the economic crash of 2008, the first black president and the polarisation of recent years, including Black Lives Matter. And they aren't even 30 yet!"

Natalia (again in the front row, third from left) joins her classmates and Kay Daniels for the documentary, 9/11 Kids

Tensions between the community and the police emerge as one of the key themes of the film, and Natalia has first hand experience of them. Growing up, she says she saw cousins being beaten by police for not carrying ID. She says police would stop her and her friends in the area and imitate and mock their accent.

"We were a joke to them," she says. "Our culture was a joke to the police."

Crime rates in Newtown are some of the highest in the state of Florida, a statistic that some community leaders, and Natalia, put down to the area being "over-policed".

"It's the kind of area where if you call them for help, it'd take them about an hour to get to you," Natalia says. "But if you have a party, the police will be there in five minutes to arrest people for small amounts of drugs."

The tensions came to a head in 2018, when Natalia's brother, Jeremy, a state football player with a scholarship to university, was shot three times by a police officer. He was 19, unarmed, and sitting in his car with a friend.

Jeremy survived the attack but was subsequently jailed for a minor drug offence, which Natalia says is often what happens when young black men are targeted by the police. His arrest prompted Black Lives Matter protests in Newtown.

"They found a way to lock him up," she says. "He had his whole career in front of him with his football. When he's out we have to get him back on track and make sure he can fulfil that."

Natalia is now 26, and lives in Newtown with her boyfriend and her two children. She runs a babysitting business, caring for children in the community and helps out in a pop-up business making and selling teddy bears. Her mother, Stephanie, died of a longstanding illness in August, a blow to a family still reeling from Jeremy's imprisonment.

"Right now everyone is on a pause," she says. "But I'm keeping my mindset optimistic. I'm not angry. I honestly feel I'm destined for greatness and when I rise, I'll take my family with me."

Natalia embraces Kay Daniels

Natalia's experience of reading reports of 9/11, and hearing inaccurate stories about her brother's arrest, means she doesn't believe everything people say, or what they write in the media, or on social media. She is careful about coming to conclusions.

"I don't make snap decisions. I weigh everything up."

Thinking things through for herself, she has even found herself defending politicians, including President Trump, to her friends.

"I think he's made life easier for people to start businesses and the economy was good under him," she says. "But he's done a whole lot of bad too."

Although more than a quarter of a million voters under 30 in Natalia's home state of Florida have already cast votes in this election - five times more than in 2016 - she isn't sure how, or if, she'll vote. She's voted in the past but things feel different this time.

"I've seen what it's like to have politicians and the media come by our communities every four years and pretend that they care - and nothing changes," she says. "The people wanting our votes aren't from and don't speak for the community."

Natalia thinks something has changed since 2001, when the media and politicians "controlled the narrative" - the rise of social media, for one thing, and the Black Lives Matter movement. "Now we're getting to have our voices heard and our generation has lots of ways to express ourselves," she says.

Florida is one of the most influential swing states in US presidential elections; how it votes is a strong indication of who the next president will be - its choice has been the country's choice in the case of the last six presidents. Natalia's vote most definitely counts.

"I don't want to say that votes don't count, they do count, but at the end of the day will they make the change of what we want to see happen in our communities - or do we have to do that ourselves?"

You may also be interested in:

James Smith has never wanted much to do with the police but he called them to check on his neighbour in the Texas city of Fort Worth, because it was late at night and her front door was wide open. Soon afterwards he heard a gunshot, and later saw the dead body of a 28-year-old woman, his neighbour's daughter, carried out on a stretcher.