Revenge of the secretaries: The protest movement that inspired the film 9 to 5

- Published

The hit comedy 9 to 5, in the US the second-highest grossing film of 1980, saw three female office workers kidnapping their lecherous boss and starting a workplace revolution. But not everyone knows that the film, starring Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lily Tomlin, was inspired by a real-life movement to empower women in the workplace.

Karen Nussbaum's favourite scene in the film 9 to 5 is when Violet (Lily Tomlin), Doralee (Dolly Parton) and Judy (Jane Fonda) are in a cocktail bar, drowning their sorrows after a hard day at the office. Violet has been overlooked for promotion once again, Doralee is being sexually harassed by their boss, and Judy is upset that a colleague was unjustly fired.

"Couldn't we just all get together and complain?" says Judy.

"Complain to whom?" asks Doralee.

The women have come up against a familiar snag - when your boss is the problem, who can you turn to? On the face of it, you're stuck.

"I love it because it captures how restrained people's imagination is," says Nussbaum, whose campaigning on behalf of office workers inspired the film. "We can do more than complain - that's why you need to battle."

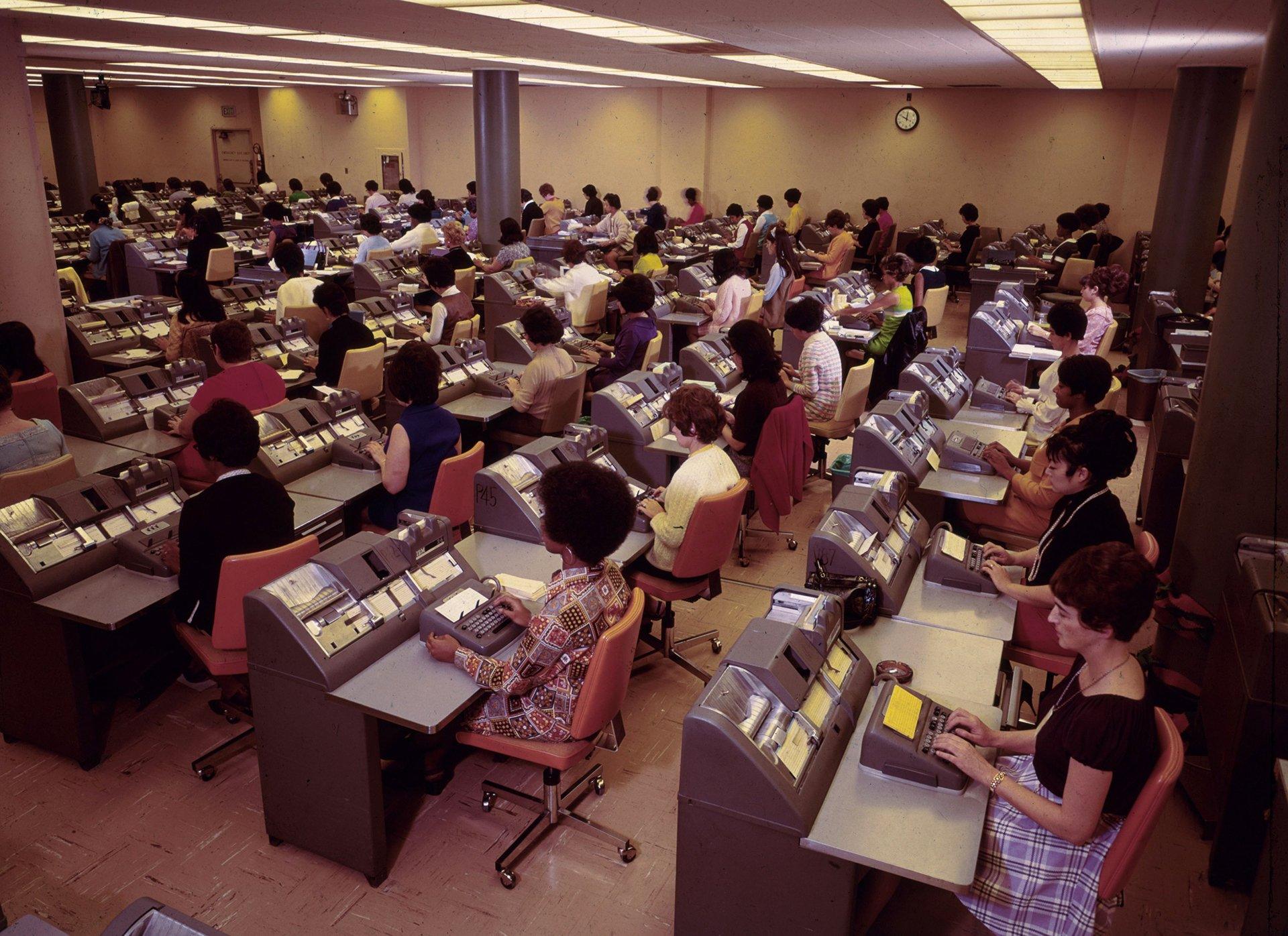

In 1970, Nussbaum was working as a typist and office clerk in Boston. The work was repetitive, unappreciated and badly paid, without any opportunities for advancement. But it was what most women did. Secretaries "were like the wallpaper, they hardly existed to most people, no-one even gave them a second thought," says Nussbaum.

"For the most part, nobody knew who you were. I had a friend whose boss could not remember her name."

Nussbaum's work may have been unrewarding, but it allowed her to focus on her real passion: activism. Like many young people during the 60s and 70s, Nussbaum was protesting against the Vietnam War, campaigning for women's rights and civil rights. When Monday morning came around, she would swap her placards for a typewriter and get on with her clerical duties.

Then one day, while picketing in support of striking waitresses, she had a revelation: she could fight injustice in workplaces like her own too.

Karen Nussbaum spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service (Producer Fiona Woods)

She got together a group of friends to discuss what they could do. "We talked for a year, which is the kind of thing you did in the early 1970s," she says.

One of them was Nussbaum's university friend, Ellen Cassedy, another clerk typist who was sick of the way she was being treated. Her own moment of clarity came when her boss called her into the office to remove a calendar from his wall, while he stood right next to her. "Why couldn't he do that himself?" she thought.

"The most common task for most clerical workers was probably getting coffee for the boss," says Nussbaum.

"This notion that you were there as the office wife, to do anything that was asked of you - we didn't know how to express what was wrong with that, but we sure felt like it was wrong. People were quietly seething."

When they looked into it, they made the shocking discovery that office workers were the largest sector of the workforce - more than construction and manufacturing workers combined - yet they didn't have a voice.

So they started a newsletter called 9to5 (without spaces, unlike the film title), which they distributed at bus stops on their way to the office. "It was a way to say to thousands of women: 'Talk to us, is this happening to you? Well, you're not alone,'" says Nussbaum.

Women started using it as a forum to share their experiences.

"There's a wonderful letter from a woman named Joyce, who said, 'I'll be called 'girl' till the day I retire without pension,' says Nussbaum.

"In those 10 words or so she captures all of the conflicts - the insult of never being seen as an adult, working your whole life, and then not getting the basic provisions of a lifetime worker - a pension."

Women workers were involved in a number of struggles at the time, such as the fight for maternity benefits. "Pregnancy was not considered a health condition, because it only happened to women, and so it wasn't discrimination to not give maternity benefits. It was just a feature that only happened to some people," says Nussbaum.

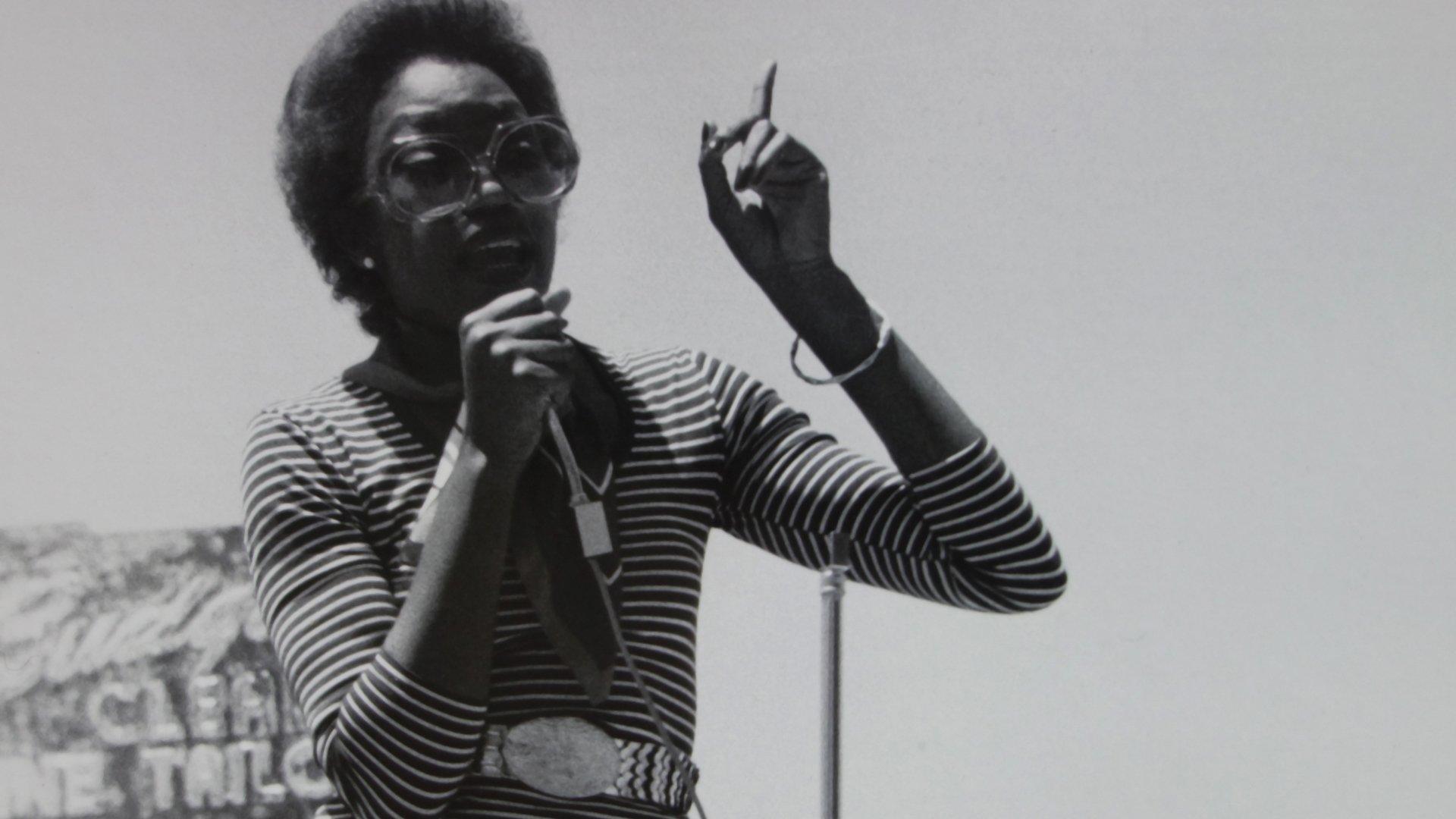

In November 1973, 9to5 began organising public meetings. "If we don't fight for dignity and respect on the job, who's going to fight for us?" Nussbaum said in a speech included in a new documentary, 9to5: The Story of a Movement.

Cassedy quit her job to work for the 9to5 Association full-time and they set up base in a tiny office in the Boston YWCA, planning actions their members could get behind, even if they didn't think of themselves as activists or feminists.

Ellen Cassedy and Karen Nussbaum in the 9to5 office at the YWCA

"People would have been scared to hand out a leaflet on a street corner - what if their boss walked by?" says Cassedy. "So we developed this kind of personality, this kind of sassy in-your-face, light-hearted way of going about things. It worked."

Humour and ridicule became their secret weapons.

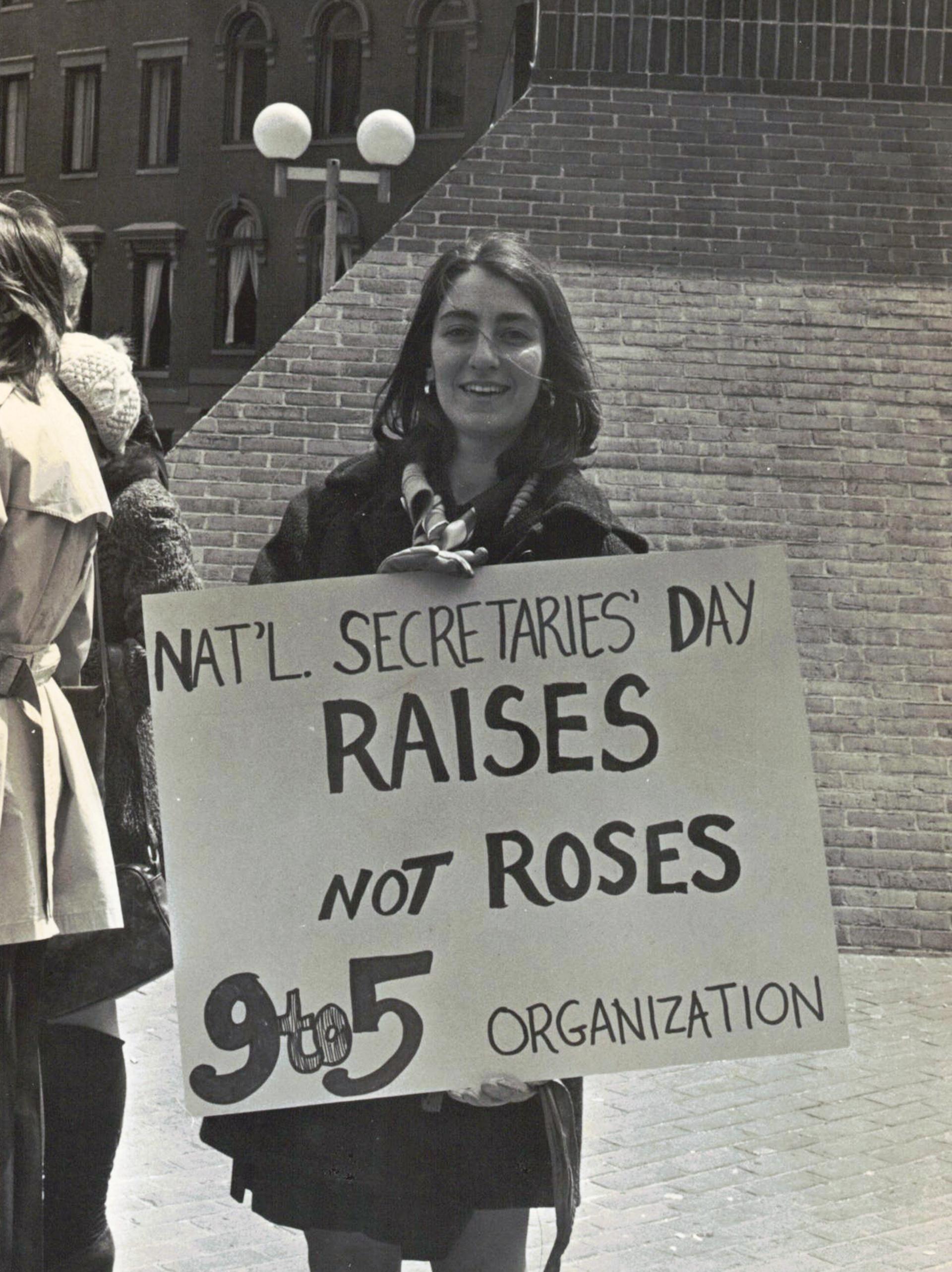

They decided to target National Secretaries Day, when bosses were supposed to buy their secretary a bouquet of flowers or a box of chocolates to thank them for their year of hard work.

Karen Nussbaum at the first National Secretaries' Day protest in Boston 1974

"We thought this was ridiculous, we wanted our rights 365 days a year," says Cassedy.

"So we put out the call for people to nominate the worst boss of the year, and we got hundreds of responses. There were unbelievable things - one boss asked the secretary to take his urine sample to the lab, one boss asked the secretary to type his daughter's term paper.

"One boss asked the secretary to go to a local bar with a pager, and if she saw any hot babes there that she thought he might be interested in, to let him know."

Nussbaum remembers the "14-carrot boss" from Cleveland, Ohio - he was on a diet, so his secretary's first job every morning was to peel carrots for him.

And then there was the boss who made his secretary sew up the crotch of his trousers - while he was still wearing them. He won that year.

When the worst boss was identified, 9to5 would turn up with the press in tow, putting them on the spot - and on TV.

"We always believed it was important to have fun - and to use the strength of humiliating an employer the way they often humiliated workers," says Nussbaum.

"We wanted to turn the table on employers."

They organised protests too, like the time when a woman was fired for buying her boss the wrong sandwich. He buzzed her on the intercom, screaming: "I told you to get me a corned beef sandwich on rye. This is a corned beef sandwich on white. You're fired!"

The next day 40 women picketed the office, carrying posters that said "Rye bread or no bread".

"She didn't get her job back. But she was one satisfied secretary," says Nussbaum.

As well as publishing the newsletter, 9to5 surveyed hundreds of women about their working conditions. In their responses they complained about lack of respect, lack of job descriptions and lack of opportunity. Talent gets bypassed... treated like a child... no job description... my boss swears, throws tantrums, pounds the desk - were some of the comments.

Nussbaum remembers a 60-year-old musing about why she had never been able to advance - was it because she didn't have a university degree? "She probably ran the place. But what kept her from being in charge was that she was a woman," says Nussbaum.

Some office workers did have degrees - Cassedy was a history graduate for example. (Nussbaum had given up her course to become a full-time activist.)

Committees of working women formed all over the country and 9to5 tried to empower and develop them, encouraging them to speak publicly, or write reports, wherever their talents lay.

When members voted on a 9to5 Bill of Rights, to define the movement's goals, Nussbaum was surprised at how modest the demands were - things like posting job adverts when there was a potential opportunity for promotion (rather than just giving the job to a favoured man), and to be shown respect. "They didn't even ask for higher pay. They didn't think that was in the range of possibilities," she says.

Even so, they won some solid victories on that front. In Boston they discovered that a group of employers was illegally setting office workers' wages across several organisations. Their protests prompted the state's attorney general to take action and the upshot was a 10% wage increase across the board.

Karen Nussbaum marches for equal pay

Mary Jung was an activist in Cleveland, Ohio, who helped organise a protest against unequal pay at National City Bank. Her 9to5 group had discovered that male bank staff were being paid 50% more than women with the same skills - and because the bank handled federal money, this meant it was violating anti-discrimination laws.

Jung remembers the bosses' initial attitude was one of disbelief, along the lines of: "It's bad enough that you don't want to get coffee and pick up the dry-cleaning, but now you also want to get the same amount of money as a man who has a wife and children to support?"

"It was just such an unheard-of concept for them," she says.

But eventually some of the women's demands were satisfied.

9to5 Cleveland holds an action in protest of National City Bank - Mary Jung is on the right

As well as sexism, 9to5 targeted racism in the workplace, the signs of which were everywhere. As one member says in the documentary: "Third floor was data entry - there were no white people. The second floor was for professionals - and I saw no black people."

Jung, then 23, soon became aware she had faced racial prejudice herself. "I just thought all the discrimination was happening because I wasn't a loveable person, not because I was Asian," she says. It hit her "like a thunderbolt" the moment she saw a report on discrimination against Asians published by the US Commission on Civil Rights.

Mary Jung at the protest outside Cleveland National City Bank - Karen Nussbaum is in the background

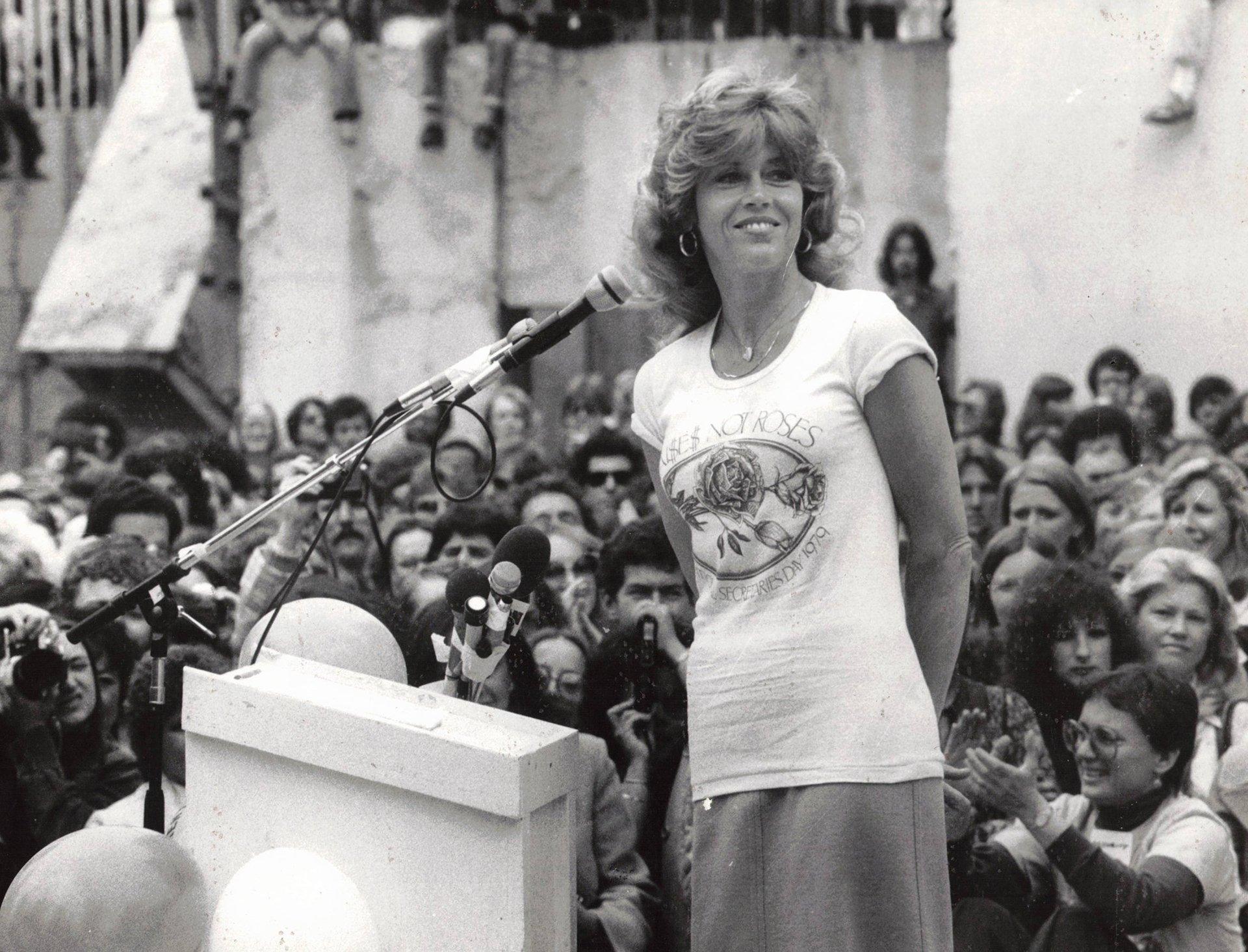

Throughout this time, Nussbaum also remained active in the anti-war movement, where she got to know Jane Fonda, who found her 9to5 stories "jaw-dropping". And when the war in Vietnam ended in 1975, Fonda had a proposal: she wanted to make a movie about the women's struggle.

Nussbaum helped write a pitch to convince the studio that there would be an audience for it. "It's the largest sector of the workforce. There are 20 million office workers, no-one ever talks about them. Once you do, they will flock to the movie theatres," she told them. The project got the green light.

Jane Fonda and Karen Nussbaum met in the anti-war movement

In 1978 Fonda brought script writers to a 9to5 meeting in Cleveland, where she spoke to 40 women about the problems they faced in their jobs. Then she asked: "Do any of you fantasise about killing your boss?"

Mary Jung was there that day, and she remembers the horrified reaction of the organisers. "Oh my God, our nice little suburban women members are being asked if they ever thought about killing their bosses!" But it turned out everyone had.

"The place really went on fire," says Nussbaum. "Rat poison in the coffee, and things that you couldn't even put in the movie: grinding the boss up in the coffee grinder [and making coffee with him] - things that were really grotesque, but this is how angry some women were."

Those women's murderous fantasies fed into the script, and saw the characters imagine hunting down, lassoing and poisoning the "sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot" who made their working lives hell.

"It unlocked this idea for the movie," says Fonda in the documentary 9to5: The story of a movement. "The entire time that we were working on the movie I could carry in my heart that this was married to a movement."

Even so, the 9to5 team worried Hollywood might get it wrong. "We had somebody on the set who was keeping an eye out for things that didn't quite ring true," says Cassedy. They vetoed the characters ordering avocado sandwiches, which you might eat in California, but not Cleveland. (This has changed in the past 40 years.)

One of their biggest concerns was that the film would focus on getting women out of the typing pool, instead of on making life in the typing pool better.

"We were very nervous," says Cassedy. "And we were absolutely horrified when marijuana was being smoked in the movie."

They needn't have worried, as they realised at the premiere.

"The minute the movie starts, the women are shouting back at the screen and jumping up," remembers Nussbaum. "There's one scene where Jane has just gotten a new job, and she's supposed to make copies on the copying machine. And the machine goes crazy, papers spewing out all over the place. One woman near me jumps up and says, 'Push the stop button!'"

Similar scenes happened all over the country.

"We didn't know that 9 to 5 was going to be a box office smash, we didn't know it was going to become an iconic movie that was probably the most successful political movie ever made. And we certainly didn't have any idea of how the song would become an anthem for the entire women's movement," says Nussbaum.

"I love how the song begins with pride - 'Pour yourself a cup of ambition' - it goes to complaints about the boss taking credit for what you do - 'You're just a step on the boss man's ladder' - and then it goes to how we all have to join together - 'In the same boat with a lot of your friends.'

"I love how in simple language it gets to the heart of the whole problem."

The success of the film marked a cultural shift.

Jane Fonda at the 9to5 Summer School in 1977

"It just completely changed the debate in the country," says Nussbaum. "Women walked into the movie theatre without a political agenda. And you walk out of the movie theatre and you think: 'That's outrageous.' You're no longer questioning whether there's such a thing as discrimination. You're past that, and you're ready for solutions."

At this point, 9to5 wanted to build on the momentum and form a new union, called District 925, for millions of clerical workers.

But the timing couldn't have been worse. "It came right at the time when corporate America had decided: 'We've had enough of this,'" says Nussbaum.

Cassedy says there was a "huge amount of backlash" and that this, combined with the rise of union-busting firms and a general decline of the US labour movement in the 1980s, meant that the hoped-for mass unionisation of women office workers never happened.

District 925 strike

In any case, with the advent of computers, the number of clerical workers soon fell dramatically. "No-one spends all day with correction tape fixing letters any more. Men are not only making their own coffee but doing their own typing," says Cassedy.

At the same time, women have gained rights that it's hard to believe once didn't exist. "You can have your own credit card, you can buy a house in your own name, you can sign your own documents - those things weren't even true when I was a young woman," says Nussbaum, now 70.

It has also become easier for women to reach the top of their profession, though Nussbaum thinks they could have achieved more if they had been more united. "To me, the heart-breaking contradiction of the women's movement over the last 50 years is that we've built a world full of self-reliant women who have no power," she says. She'd still like to see them maximise their influence through organised collective action.

So if 9 to 5 were made now, where would it be set? Cassedy thinks a call centre, a fast-food restaurant or perhaps a big delivery warehouse.

Nussbaum thinks many of the issues would still be the same: low pay, lack of recognition, sexual harassment, lack of childcare. But she says there would be new pressures too: workers on short-term contracts with no benefits or job security, unaffordable rents, new technology resulting in staff being on call 24 hours a day - never mind office hours - and providing the ability to track their every action and communication.

It would, she says, be "9 to 5 on acid".

9to5: The Story of a Movement airs in early 2021 on PBS in the US

Listen to Karen Nussbaum speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Jane Fonda: 'It's much harder to be young than it is old'

You may also be interested in:

On 10 December, Finland's new coalition government headed by five women had been in office for a year. It has dealt efficiently with the coronavirus pandemic, while drafting an ambitious Equality Programme - a programme that states, among other things, that everyone has the right to determine their own gender identity.