The homeless drug addict who became a professor

- Published

Jesse Thistle, wearing a beaded thistle around his neck

Jesse Thistle spent more than a decade on the streets and in jail. But despite this he has managed to become an expert on the culture of his Indigenous Canadian ancestors - with the help of his mother, from whom he was separated as a young child.

Sometimes, at night, feeling humiliated after a day of begging, Jesse Thistle would walk up to the fountain on Ottawa's Parliament Hill.

Sitting on the edge of the monument, he would plunge his hands into the cold water, to fish out the coins visitors had thrown in for luck. The policemen on duty always saw Jesse coming. They'd watch as he shovelled handfuls of wet change into his pockets, then chase him away.

Jesse was 32 and had recently relapsed from rehab, but he'd been living on the streets, on and off, ever since his grandparents kicked him out when he was 19.

"My grandfather was a disciplinarian - old school - he believed in work, really hard work, and he would hit us if we did bad stuff," Jesse says.

"He would say, 'If I ever catch you doing drugs, I will disown you, it's that simple,' and he meant what he said."

So the day that Jesse's grandmother saw a bag of cocaine fall out of Jesse's pocket, he was told to pack his things and leave.

"It was like my world had ended," he says. "I could see on their faces that I'd broken their hearts."

Jesse's life had been chaotic from the start. His father, Sonny, had got into trouble with the law in Toronto and had run away to northern Saskatchewan, where he met a teenager from the Métis-Cree Indigenous group.

Blanche Morrissette aged 14 in 1972, the year before she met Sonny

Her name was Blanche and she gave birth to three sons one after the other, Josh first, Jerry, and then Jesse.

Sonny drank and used heroin, and was often violent, so eventually Blanche ran away, taking the boys with her.

For a while they lived in Moose Jaw, sleeping on proper beds rather than piles of laundry and eating three meals a day. Then Sonny turned up again and told Blanche he had an apartment and a job in Toronto. Blanche was studying as well as working, and he persuaded her to let him take the boys for a few months, to give her a break.

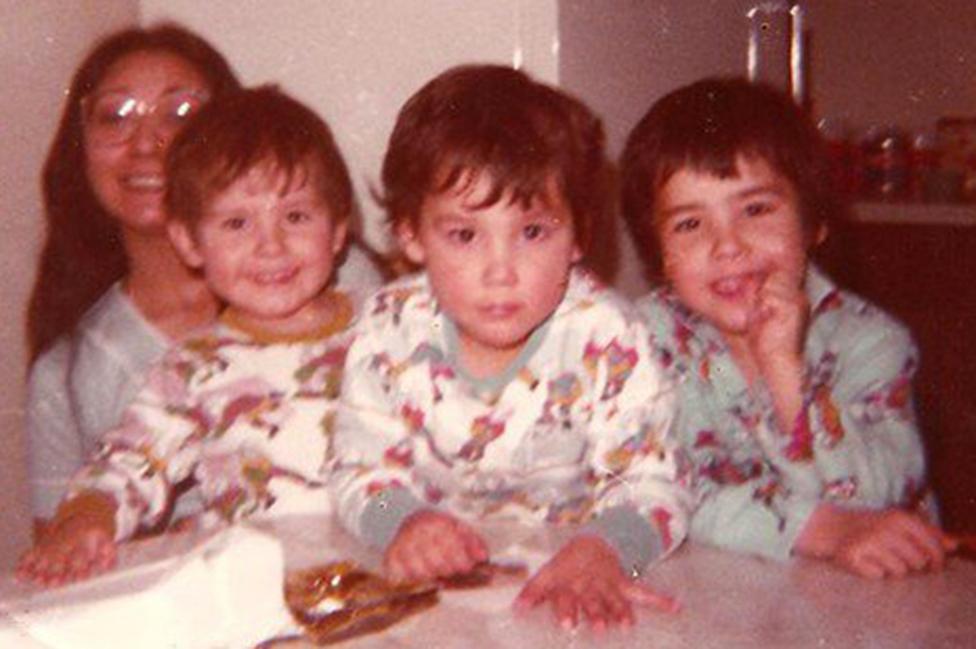

Blanche and her three sons pictured in 1980 - "before our family fell apart," Jesse says

But there was no new job, and Sonny hadn't overcome his addictions. He'd disappear for days at a time, leaving the boys - all aged under six - alone in the apartment. There was little food when Sonny was there and none when he wasn't. He taught the boys how to beg, how to shoplift, and how to roll him cigarettes by harvesting tobacco from butts picked up off the streets.

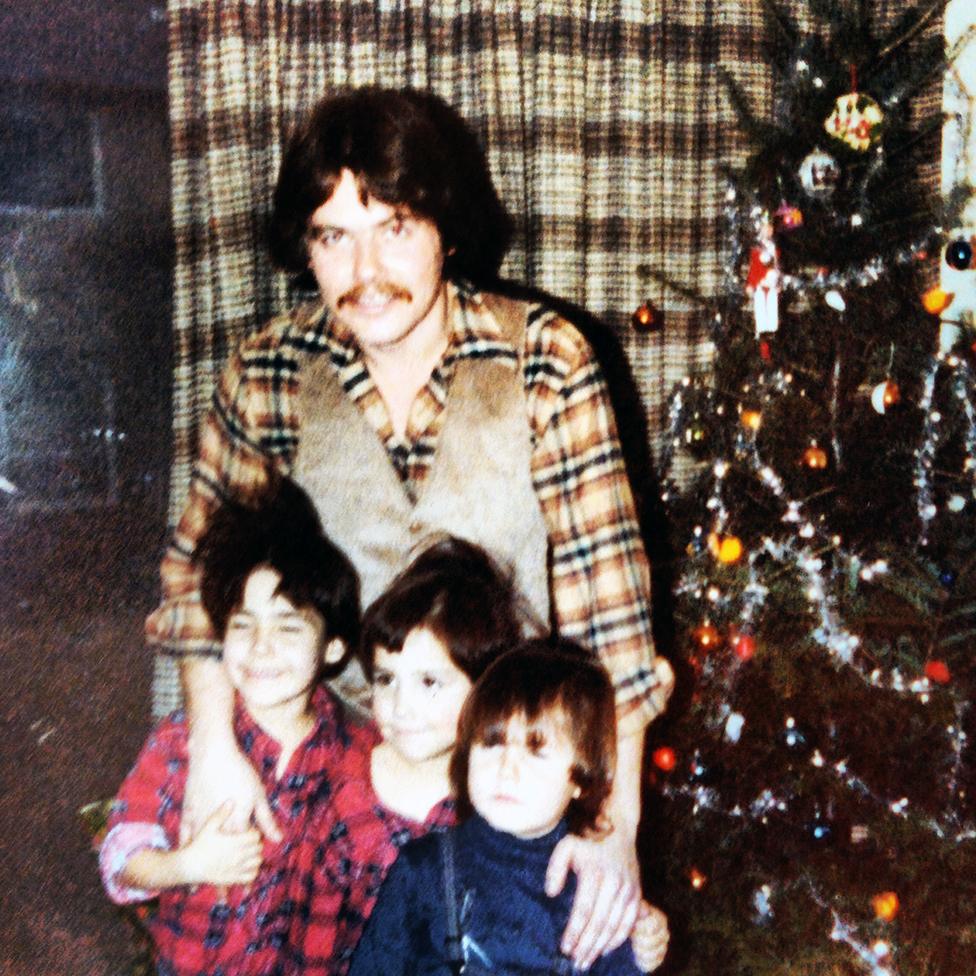

Sonny with his three sons, Christmas, 1979

It was a few months before a neighbour alerted Child Services, and police came and took the boys away. Jesse was by now aged four, and he and his brothers would never see their father again.

After a period in an orphanage and a foster home, they were sent to live with Sonny's parents.

"I assume Child Services never called my mom because back then Indigenous women were thought of as unclean, unfit and derelict of their positions as mothers," Jesse says.

"When Indigenous kids came across Child Services' desks, their natural inclination was to put them in white homes because white people were seen as prosperous and responsible. It was called the Sixties Scoop - thousands and thousands of Indigenous kids were taken that way - it was endemic."

The Sixties Scoop

Despite its name, the Sixties Scoop started in the late 1950s and persisted for more than 20 years

About 20,000 Indigenous Canadian children were removed from their homes by child welfare agencies and placed with non-Indigenous families

These children lost their names, their languages, and their cultural identity

Jesse's grandparents barred Blanche from coming to see her children for a few years, and Jesse grew up with little knowledge of his Métis-Cree heritage.

"We knew we were 'Indian' and my brother remembers living in a tipi one summer in Saskatchewan," Jesse says, "but he went around and told all the kids that, and I gotta tell you, there's no faster way to get beat up in grade school in Canada than looking native and telling white kids that you lived in a tipi."

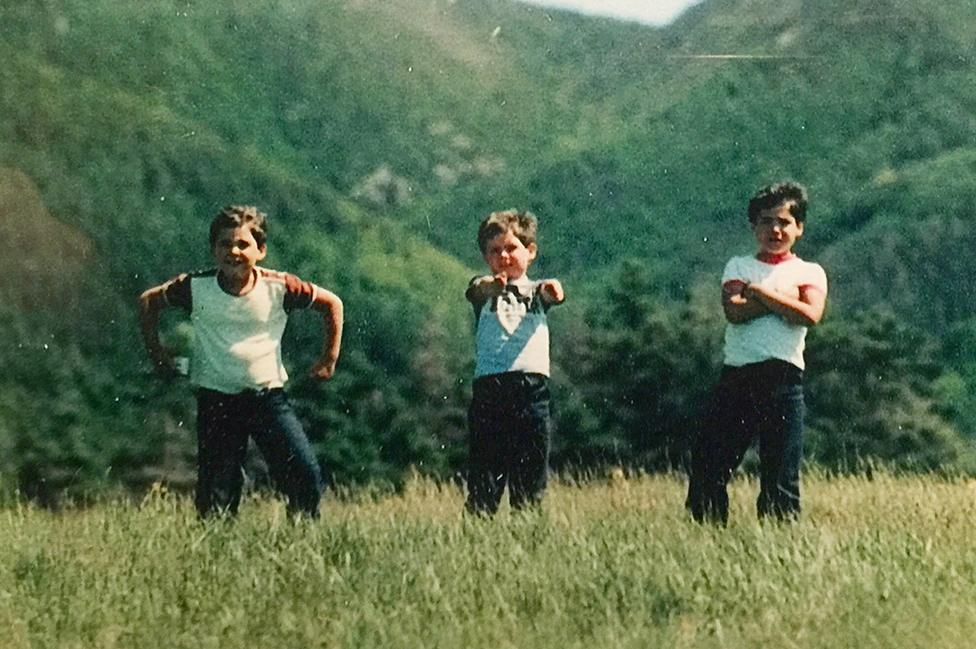

Jerry, Jesse and Josh in Cape Breton, 1980

Other families in the neighbourhood were reluctant to let their children play with the brothers, and at some stage Jesse decided that it would make his life easier if he pretended to be Italian.

"I was denying who I was," he says. "I started to hate my heritage, hate myself and hate her [my mom] because she wasn't around. I felt like she had ditched us."

At school Jesse was always fighting, was held back because of his poor grades, and never learned how to read or do maths properly. Then he joined a gang in high school and really started getting into trouble.

"We were drinking, partying, going to raves and using drugs, and that soon became my identity," Jesse says. "I would lose myself on MDMA, ketamine and crystal meth for three, four and five days in a row."

And then his grandparents kicked him out.

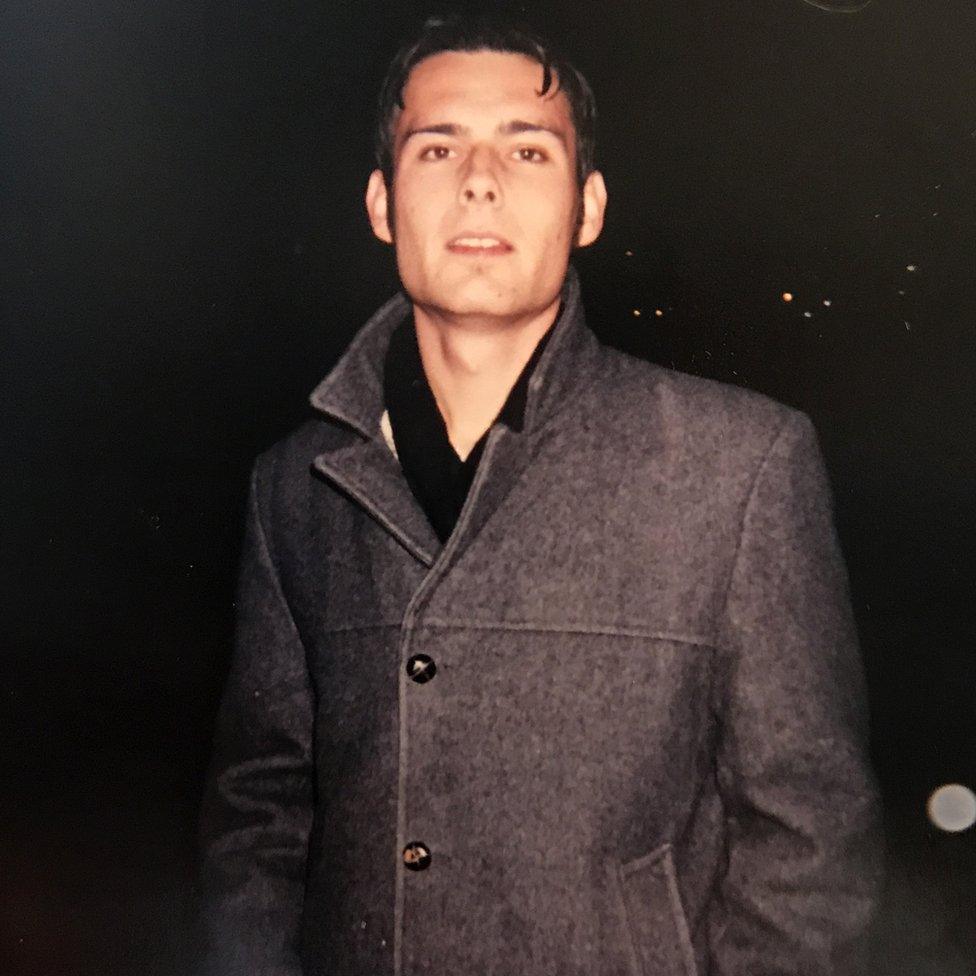

Jesse, aged 19, just before things started going downhill

Jesse hitched a lift with a friend across the country from Toronto to Vancouver, where his brother Josh, now a policeman, let him stay.

He'd borrow Josh's police badge to avoid paying on public transport, and use it to pick up girls - "Girls love the police" - or to blag free food in restaurants. But the day Josh returned from work to find his younger brother using drugs in the house, Jesse had to leave, and this time he had nowhere else to go. At the age of 20, he was homeless.

Jesse Thistle spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Jesse slept for four months in a car parked by the Fraser River just outside Vancouver, surrounded by other homeless people - the majority of them also Indigenous.

"It was horrible. It broke my heart to see all these Indigenous people with addiction issues there - and nobody cared," he says.

He sold everything he owned apart from the clothes he stood up in, but still he was starving.

After hitching back to Toronto, he drifted from sofa to bus shelter to refuge, begging to get enough money together to buy drugs and go to raves. And when a friend introduced him to crack, he was hooked from the first lungful.

It was New Year's Eve, 1999. Jesse, by now 23, had been out partying all night. The following day he went over to a friend's house. There were some people there he vaguely knew, who asked if he wanted to share a joint and if he could help them find a lift to travel out west. They said they'd buy him a pizza if he could order one for them and they'd give him a new jersey in return for his efforts.

Thinking this was the easiest work he'd ever had, Jesse, wearing his new jersey, then returned to his Uncle Ron's place - where he'd been crashing since all of his belongings were stolen from the last hostel.

Jesse and Ron sat down to watch a movie, but when a breaking news alert flashed across the screen announcing that a cab driver had been murdered in the neighbourhood the previous night and describing the two suspects, both in their late teens or early 20s, Jesse felt sick.

"They had given me the clothes that they'd done it in. They were trying to frame me for this murder that they had committed," he says. "And so I was left with a choice - keep my mouth shut - that's the code of the streets, you don't tell on people - or stand up for justice and do the right thing."

Jesse considered taking off - "running away was my way of dealing with life" - but instead went to the police. The two men who had tried to frame him were later jailed for murder.

But word got out that Jesse was an informer. "And I became a dead man walking," he says.

Old friends wanted nothing to do with him, people would lure him places so that they could ambush him, someone tried to knife him in an alley, and he was beaten so badly with a baseball bat he could barely walk.

"I was always on the run, always fearful for my life, always on high alert," he says. "They call it hyper-vigilance - I just had to survive and bounce from place to place."

In despair, Jesse stole a large quantity of painkillers from a pharmacy and swallowed them all before he could think twice about it. This led to a spell in hospital, but no change in his behaviour.

A few of Jesse's police mug shots

One evening after becoming locked out of his brother Jerry's apartment in Toronto, Jesse fell three-and-a-half storeys to the ground while trying to break in. He survived and landed on his feet, but his right heel was shattered, his right ankle joint destroyed and both his wrists broken. Doctors couldn't believe that Jesse hadn't been killed. But his real problems began after he was discharged from hospital, when infection set in.

Jesse was smoking crack to dull the pain in his leg, but when his toes started turning black and his toenails began falling off he realised he needed help.

"My leg had rotten flesh, it was starting to go necrotic and it was gangrenous," he says.

He vaguely remembers doctors telling him that his leg may have to be amputated, and that if the infection spread to his heart or brain it could kill him. In panic, Jesse fled.

"I wanted to hide from the world and from my addictions, from all the mistakes and all the people that I'd hurt along the way. I just wanted to rot away and die," he says.

"I thought, 'Why don't I do a crime and go to jail? I'll be safe in there, have a place to rest, access to food and medication.'"

So he held up a convenience store and helped himself to the takings - but instead of waiting to be arrested, as he'd planned, he jumped into a large rubbish bin at the back of the shop and hid.

"I was in the garbage bin, thinking, 'I can't even rob a store properly,'" Jesse says.

He later discovered he'd taken less than $40 (Canadian dollars), and after a few weeks of drug-aggravated paranoia - imagining that he was about to be arrested at any minute - he turned himself in.

"I did it," he told the police, "I'm the guy who robbed the store. Now lock me up and throw away the key."

Prison was an unlikely turning point for Jesse.

He received the medical help he so urgently needed for his leg, which quickly began to improve.

But there was no support to come off the drugs and alcohol he'd been addicted to since he was a teenager, and he went through a "horrible, horrible" withdrawal, involving agonising seizures in solitary confinement.

Surprisingly, the experience spurred him to resume his education.

"To fight the cravings from crack I started re-teaching myself how to read and write properly," he says.

After his release from prison, Jesse went into rehab to continue this work, while also dealing with his addictions.

"I'd stay up late every night looking over encyclopaedias and my grades started topping the charts. I took etiquette courses to re-teach me how to eat at a table and take care of my hygiene - all the things that I'd forgotten because I'd been drifting around so long. I felt good about myself for the first time in many, many years."

It wasn't plain sailing. He relapsed at one point, returning to the streets to beg - and take money from the Parliament Hill fountain - only managing to get back on track after he was sentenced to a one-year stint back at the same rehabilitation centre.

While there he received a strange email - a woman was looking for him, it said, and there was a number to call. It turned out to be his mother, whom he'd seen on only a handful of occasions since she'd let Jesse and his brothers go with their father to Toronto as small children.

Shaking and through tears, Jesse called Blanche but was so overwhelmed that he had to hang up several times while they were talking.

"I was just terrified of being rejected and terrified of love," he says. "But it was a beautiful conversation - it was like a rain quenching the prairies after a long drought, that's what it felt like."

Then more unexpected family news came, a message from his grandmother - the first contact he'd had with her since being banished from his grandparents' home years previously.

She was dying, she said, and asked Jesse to visit her.

"She gave me a tongue-lashing," Jesse says. "She was like, 'I'm really disappointed in you. I want you to make me a promise - follow through with this education, go to university, and go as far as you can.'"

Jesse swore that he'd do as his grandmother asked. He urged her to get better and they hugged before Jesse returned to rehab. Two weeks later she died.

The day after his grandmother's death, Jesse received a message of condolence from an old school friend of one of his brothers.

"I think I fell in love with Lucie at that moment just because she was kind," Jesse says. "I light up thinking about it even now."

Jesse and Lucie started talking often, sometimes for hours at a time on the phone, and they'd Skype one another regularly.

A picture Lucie sent Jesse while he was in rehab

"I had this wall of about 100 different shampoos, soaps and body cleansers that I'd put behind me to show her that I was clean and that I could take care of myself," he says. "I was really insecure because of the life that I had lived and I wanted to impress her."

When Jesse finally left rehab in 2009 Lucie gave Jesse a place to stay and eventually they became a couple.

"I thought I'd won the lottery - I was just a street guy, I don't know what she saw in me," Jesse says, "but when someone loves and trusts you that way, you just want to give it your all."

Jesse and Lucie's wedding day, 2012

Lucie helped Jesse find a restaurant job, cutting French fries - "I made sure I was the best damn fry cutter in the whole city," he says - and within two-and-a-half years they had married.

Jesse started a history degree at Toronto's York University that same year, aged 35.

"It was terrifying. I'd brought a pen and a pad of paper to take notes, and I looked around me in the lecture hall and all these kids had laptops and smartphones," he says.

"I remember being the old man among all these young kids that were way, way smarter than me. I sat at the front and nobody wanted to talk to me."

In his second year, Jesse was set an assignment to research his family history and reached out to one of his aunts in Saskatchewan who'd been doing a lot of research.

"She sent me her link to ancestry.com, and I saw that I came from a long line of chiefs, political leaders and resistance fighters, and that filled me with such pride that it fired me up to want to know more and more," he says. "I knew that the key back to myself was through this assignment - I poured my heart into it."

Jesse wrote about his Métis ancestors and what had happened at the Battle of Batoche during the North-West Rebellion of 1885 - a violent, five-month insurgency his ancestors fought against the Canadian government, because they believed that their rights, their land, and their survival as a distinct people were under threat.

Jesse's assignment was passed to a professor, an expert in Indigenous history, who immediately hired him as her research assistant.

Jesse was flown back to Saskatchewan to reconnect with his mother and aunts in 2013. Now aged 37, this was only the fourth time he'd seen his mother since he'd been taken into care at just three-and-a-half or four years old.

"It was like a beautiful homecoming," he says.

Blanche and Jesse pictured in 2013 in Fish Creek, Saskatchewan - the site of one of the famous battles of the 1885 North-West Rebellion

At the road allowance where his Métis family had settled 150 years earlier, first in tents and later in log cabins, Jesse fell to his knees.

"All those memories came rushing back of who I was and who our people were, and it just filled me up in every good way."

The road allowance in Park Valley, Saskatchewan, where Jesse's maternal grandparents lived, pictured in the early 1950s

Soon Jesse's research was winning awards. He graduated as the top student in his faculty and since then has picked up two competitive doctoral scholarships, has almost finished writing up his PhD, and now teaches Indigenous history as an assistant professor at York University.

"I get a lot of Indigenous youth coming into my classroom looking for a connection back to their ancestry," he says. "I help them understand who their ancestors were and why their families have ended up where they are. It's a beautiful thing to watch people get to know their history."

And Jesse now hires his mother, Blanche - whose father was a trapper "who hunted and picked berries and fished" - as his own research assistant.

"She's an insider and she knows the community, who the elders are and the stories that I need to hear," Jesse says.

"I don't think I'd have that access without her. It's great because we can work through our broken relationship as son and mother - it's not always easy, but it's beautiful. We're just joyous to be in each other's company and I say that our research methodology is based on love."

Opposite Parliament Hill, Ottawa in 2013 - Jesse and Lucie came here on their first date and return every year, "to remember how far we've come"

Although Jesse isn't religious, he believes his grandmother somehow brought Lucie to him, as a lifeline, to help him start again.

He often thinks about the men who tried to frame him for the murder and worries about acts of retribution. Deep down he's sorry about what happened, he says, and that he was put in a position where he had to protect himself. But he's lived a good life and if they come for him now, "it is what it is."

He still struggles with the legacy of his addictions.

"I still fantasise about using crack cocaine, it never goes away. I just have to learn to manage it," he says.

"I use a trick. I'll say, 'Yeah, I want a nice, big rock today, but you know what? I'll use tomorrow.' And then when tomorrow comes I'll say that again. I can handle this tomorrow-never-comes scenario - I've been doing it for 12 years - but infinity without the drug is too much to handle."

Meanwhile, the pain in his right foot, more than a decade after his fall, reminds him every day that he's lucky to be alive.

He now has a partner and a job, has restored his relationship with his mother and reconnected with his roots. But there is still one important thing missing.

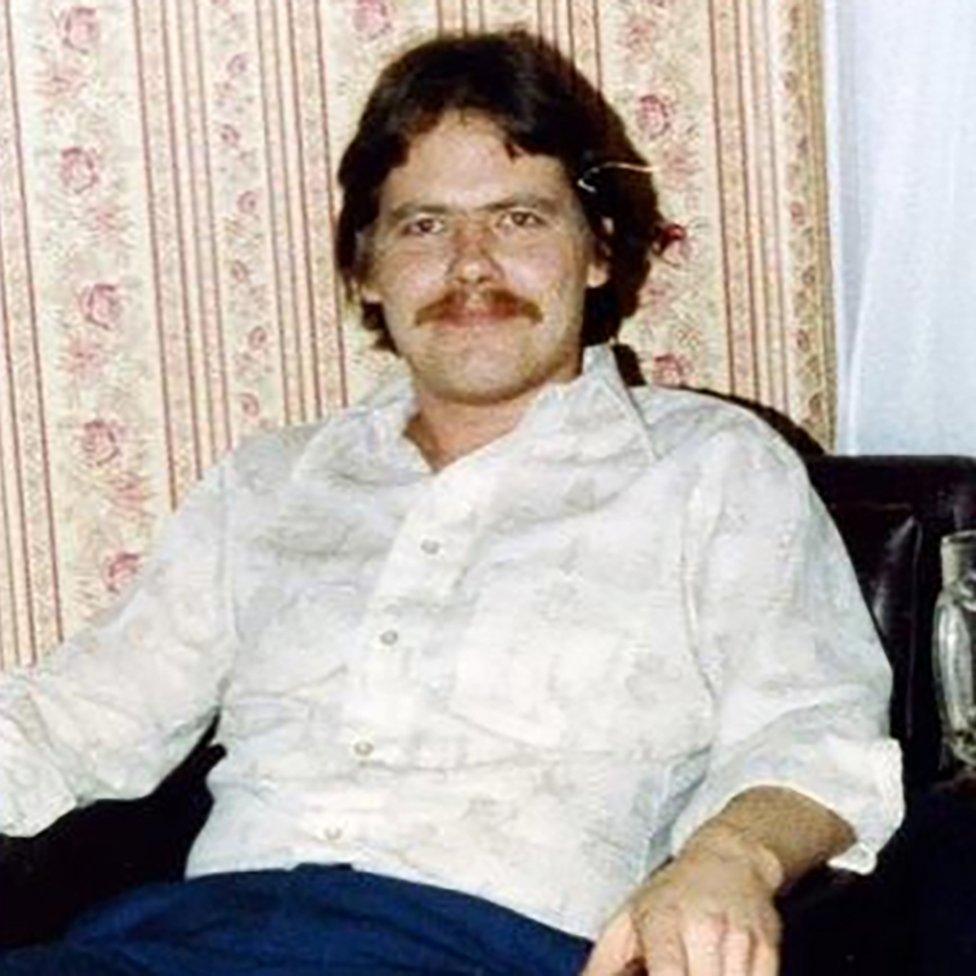

Cyril "Sonny" Thistle, pictured in 1981

For as long as he can remember, Jesse has always hoped that his father, Sonny Thistle, would come back into his life. But a chance meeting some years ago with an elderly man threw that into doubt.

"You could tell this random dude was a street person or from prison, and he's like, 'Nobody told you, son? Whatever trouble your dad was running from, whatever people, they got him - they killed him in 1982.'"

Jesse took the news to the police and officially reported his father missing.

"There are some hospital records of him in 1982, there's his police contact file, and details of where he was incarcerated, and that's it," Jesse says. "He just evaporates into thin air - he vanishes."

Jesse knew that his father was dealing drugs and would rip people off before fleeing to the next town.

"And if you do that to someone involved in organised crime, then they make examples of people - that's what they do, that's part of the business," he says.

But while it was devastating to learn that his dad might be dead, it was comforting to think that there was a reason why he had never been in touch.

"What better excuse is there for a father not coming home than he's dead?" says Jesse.

He hasn't given up all hope, though, that his father might still be alive.

"There's a possibility that someone somewhere knows something, so we're still looking for him," he says.

"Part of me doesn't want to accept that he's gone."

Images courtesy of Jesse Thistle, unless otherwise stated

Jesse Thistle is the author of a memoir titled From the Ashes

You may also be interested in:

Each year, dozens of Canadian Aboriginal women are murdered or disappear never to be seen again. Some end up in a river that runs through the heart of Winnipeg.