Lobotomy: The brain op described as ‘easier than curing a toothache’

- Published

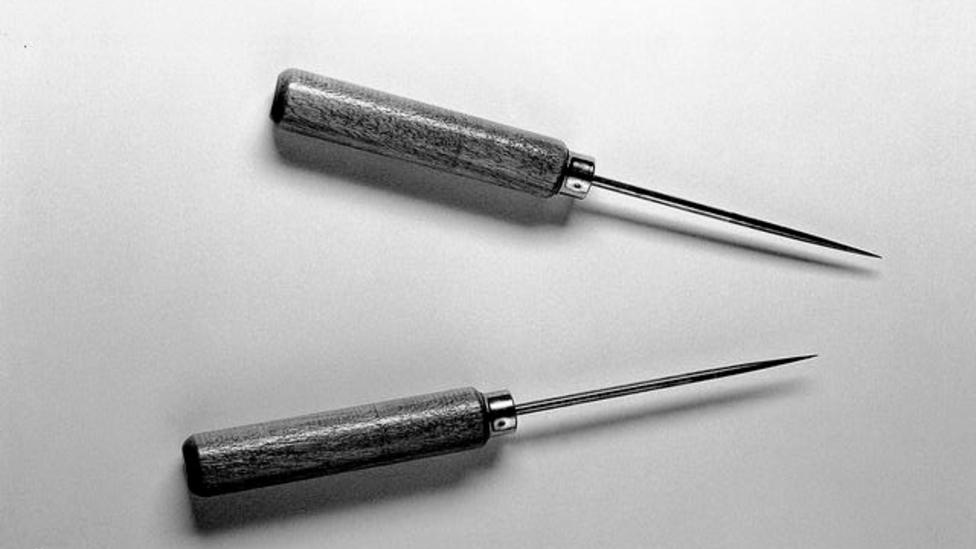

Lobotomy instruments that once belonged to Walter Freeman

There was a time when people with severe mental illness might be given an operation to sever connections in the brain. Lobotomy became one of the most notorious surgical procedures of the 20th Century, writes Claire Prentice, but retired neurosurgeon, Henry Marsh, who once carried out a modified version of the operation, tells her it's wrong to divide doctors into heroes and villains.

It seems incredible today, but lobotomy was once hailed as a miracle cure, portrayed by doctors and the media as "easier than curing a toothache".

More than 20,000 lobotomies were performed in the UK between the early 1940s and the late '70s. They were typically carried out on patients with schizophrenia, severe depression or Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) - but also, in some cases, on people with learning difficulties or problems controlling aggression.

While a minority of people saw an improvement in their symptoms after lobotomy, some were left stupefied, unable to communicate, walk or feed themselves. But it took years for the medical profession to realise that the negative effects outweighed the benefits - and to see that drugs developed in the 1950s were effective and much safer.

Writers and film directors have not been kind to the doctors who carried out lobotomies. From One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and the Netflix spin-off series, Ratched, to Suddenly Last Summer, they portray sadistic surgeons preying on the vulnerable and leaving dead-eyed patients in their wake.

Jack Nicholson as Randle McMurphy being restrained in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest

Sarah Paulson as Nurse Ratched (right) in a scene from Ratched

The truth is more complex. Lobotomists were often progressive reformers, driven by a desire to improve the lives of their patients.

In the 1940s, there were no effective treatments for the severely mentally ill. Doctors had experimented with insulin shock therapy and Electro-Convulsive Therapy with limited success and asylums were filled with patients, including shell-shocked soldiers, who had no hope of a cure, or of going home.

It was against this background that Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz developed the lobotomy - or leucotomy as he called it - in 1935. His procedure involved drilling a pair of holes into the skull and pushing a sharp instrument into the brain tissue. He then swept it from side to side to sever the connections between the frontal lobes and the rest of the brain.

"It was based on this terribly crude, simplistic view of the brain, that the brain was a simple mechanism, and you could just sort of stick things into it. The idea was that you had these thoughts running round and round and by interrupting the circuit you would stop these distressing, obsessional thoughts," says the neurosurgeon and writer, Henry Marsh.

"In reality the brain is utterly complicated and we don't even begin to understand how it all interconnects."

Listen to Archive on 4: Easier Than Curing A Toothache? The Story of Lobotomy on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 on Saturday 30 January

Moniz claimed that his first 20 patients had experienced a dramatic improvement - and a young American neurologist, Walter Freeman, was greatly impressed. With his operating partner, James Watts, he carried out the first lobotomy in the US in 1936; the following year, the New York Times referred to the operation as "the new 'surgery of the soul'". But to begin with it was complicated and time-consuming.

While working at St Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC, the largest mental hospital in the country, Freeman had been horrified by "the waste of manpower and woman power" he witnessed there. He was keen to help patients get out of hospital, and set himself the goal of making lobotomy quicker and cheaper.

In 1946 he devised the "transorbital lobotomy" in which steel instruments resembling ice picks were hammered into the brain through the fragile bones at the back of the eye sockets. The operating time was drastically reduced, and patients did not need an anaesthetic - they were knocked out before the operation using a portable "Electro-Shock" machine.

Walter Freeman demonstrating his transorbital lobotomy technique in 1949

Freeman would drive across America during the long summer holidays to conduct his "ice-pick lobotomies" - sometimes taking his children along.

Initially described as a surgery of last resort for psychiatric patients for whom all other treatments had failed, Freeman began to promote lobotomy as a cure for everything from serious mental illness to post-natal depression, severe headaches, chronic pain, nervous indigestion, insomnia and behavioural difficulties.

Freeman's colleague, Dr James Shanklin, uses electrical apparatus to prepare a patient for transorbital lobotomy

Many patients and their families were grateful to Freeman, who kept boxes filled with the letters of thanks and Christmas cards they sent him. But in other cases the results were disastrous.

Freeman's patients included Rosemary Kennedy, sister of the future US president John F Kennedy. She was left incontinent and unable to speak clearly after a lobotomy at the age of 23.

Over the course of his career, Freeman conducted lobotomies on 3,500 patients, including 19 children, the youngest just four years old.

Freeman's counterpart in the UK was the neurosurgeon, Sir Wylie McKissock, who carried out his own variation of the lobotomy on about 3,000 patients.

"This is not a time-consuming operation. A competent team in a well-organised mental hospital can do four such operations in two to two-and-a-half hours," he boasted. "The actual bilateral prefrontal leucotomy can be done by a properly trained neurosurgeon in six minutes and seldom takes more than 10 minutes."

Thanks in large part to McKissock, more lobotomies were carried out in the UK, per head of population, than in the US.

As a medical student in the 1970s, Henry Marsh took a job as a psychiatric nursing auxiliary in a mental hospital, on what he describes as "the end-stage ward where the burnt-out cases went to die". There he saw first-hand the devastating effects of lobotomy. "It was painfully apparent to me that there was no proper follow up of these patients at all," he says. "The patients who were the worst, most apathetic, sort of ruined patients were the ones who had been lobectomised."

They had all been operated on by McKissock and his assistants.

Later, after Marsh had qualified as a neurosurgeon, a modification of the procedure, known as a limbic leucotomy, was still in use. Marsh describes it as "a sort of microscopic version, much more refined, of the sort of lobectomies people had been carrying out many years earlier".

I didn't like doing them, and I was rather glad to give up the practice fairly shortly after I became a consultant

He himself performed this operation on a dozen patients with severe OCD until as recently as 1990.

"They were all suicidal, they had failed all other treatments, so you know I didn't feel particularly anguished about it, but I preferred not to do it," he says.

"I didn't see the patients afterwards, I was purely a technician. I was assured by the psychiatrists involved that the operations were a success."

Neurosurgeon Henry Marsh in 2015

I ask him how he feels about these operations now. "I didn't like doing them, and I was rather glad to give up the practice fairly shortly after I became a consultant."

In the early 1960s, about 500 lobotomies were carried out each year in the UK, down from 1,500 at its peak. By the mid-1970s this number had dropped to around 100-150 a year, nearly always involving smaller cuts and more precise targeting.

The introduction of the 1983 Mental Health Act introduced tighter controls and more oversight. Today psychosurgical operations are rarely carried out.

Howard Dully, who was given a lobotomy by Walter Freeman at the age of 12, says he tries to avoid thinking about how different his life might have been if he hadn't had it, for fear that anger would overwhelm him.

To me it's insane. I mean you're talking about a brain. Shouldn't there be some precision involved?

"I've tried to piece my life together. It took a long time," he says. "I got into a lot of trouble as a young adult — drugs, and alcohol and criminal activity, trying to steal and make money and make a living. It's very hard to do."

Dully feels that the operation, carried out because he had been clashing with his stepmother, cast a shadow over every aspect of his life.

"You don't walk up to people and say, 'Hi, I had a lobotomy,' because if you do they ain't going to be around you long," he says.

Sixty years on, he can remember the operation in vivid detail.

"They lifted up the eye and went into the corner and tapped it through and wiggled it around with this egg beater thing," he says.

"To me it's insane. I mean you're talking about a brain. Shouldn't there be some precision involved?

Howard Dully on recovery from 'ice-pick' lobotomy

Lobotomy had had its critics from the outset, and the chorus of opposition grew louder as the poor results became apparent.

Walter Freeman, who initially claimed to have a success rate of 85%, was discovered to have a fatality rate of 15%. And when doctors investigated long-term outcomes for his patients they found that just one-third could be regarded as experiencing some improvement, while another third were significantly worse off.

One former advocate for lobotomy in America stated: "Lobotomy was really no more subtle than a gunshot to the head."

Fifteen years ago, a group of doctors and lobotomy victims and their families campaigned to have Egas Moniz stripped of the Nobel Prize for Medicine he won in 1949 for devising lobotomy. But the Nobel Foundation, whose charter states that its awards may not be withdrawn, refused to comply.

Looking back, how should we view the people who carried out this most controversial medical procedure?

"This business of dividing doctors into heroes and villains is wrong. We are all a mix of both, we are a product of our time, of our culture, of our training," says Henry Marsh.

"The generation of surgeons who trained me had, I wouldn't say god-like powers, but they had enormous authority, nobody questioned them or queried them and I can think of some of the people who trained me who were essentially decent people who had been corrupted by this power and became a little bit monstrous as a result."

You may also be interested in:

For years doctors in the US made little attempt to save the lives of premature babies, but there was one place distressed parents could turn for help - a sideshow on Coney Island. Here one man saved thousands of lives, writes Claire Prentice, and eventually changed the course of American medical science.