Mayday: How the White Helmets and James Le Mesurier got pulled into a deadly battle for truth

- Published

A White Helmet rescues a child from a bombed building

The British man behind the Syrian civil defence group, the White Helmets, found himself at the centre of a battle to control the narrative of the Syrian war. Russian and Syrian propagandists accused his teams of faking evidence of atrocities - and convinced some in the West. The battle for truth formed a backdrop to James Le Mesurier's sudden death in Istanbul in November 2019.

With the setting sun reflecting in the water and the lights of Istanbul twinkling on the horizon, the wedding guests sat around lantern-lit tables: diplomats from several countries, military officers, journalists and activists who had flown in from around the world to see James Le Mesurier get married.

A dashing former army officer in his 40s, Le Mesurier had made his name as the co-founder of the White Helmets - the group of several thousand young Syrian men and women who pulled survivors and bodies from the rubble of bombed-out buildings in rebel-held areas of the war-ravaged country.

The woman he was marrying, Emma Winberg, once worked for the UK Foreign Office but had latterly been helping him manage the White Helmets. She was his third wife.

The couple lived in a traditional white wooden house overlooking the Marmara Sea on Buyukada island, off the coast of Istanbul. The small island once had a reputation for hosting subversives and spies - Trotsky lived there in a similar wooden house a few years before his fateful meeting with the icepick in Mexico. These days it's popular with journalists, artists and those wanting to escape the chaos of the city.

The wedding party, in summer of 2018, was held in the garden of the couple's home with the bride and groom dressed like old-fashioned movie stars. Le Mesurier was carried on the shoulders of his Syrian guests as they bounced him around in a traditional arada sword dance - his face flushed and glowing.

It was a romantic setting and it was obvious the couple was very much in love. But if you had been able to listen in to the guests, you wouldn't have heard the usual wedding chatter - the main topic of conversation among the champagne and canapes was the ongoing conflict in Syria.

The war was always present - even on their wedding day. They found it impossible to separate their work and their private lives.

Emma knew their future together wouldn't be stress-free. "We often said, as bad as it gets, we will have each other. We knew it would be an adventure," she says.

And after the fairy-tale wedding things did get bad - far worse than Emma could have imagined. In just 18 months, James was dead.

Spoiler alert: This is the story told in the BBC's 11-part Mayday podcast - if you prefer to listen to the audio please click here, otherwise read on (this story is a 23-minute read)

On 11 November 2019 at around 05:00, a worshipper on his way to morning prayers discovered James Le Mesurier's crumpled body lying on the cobblestones in a narrow alleyway in Istanbul. He had apparently fallen from the apartment above his office, three floors up. Emma was still asleep in their bed when the police banged on the door and woke her.

Turkish detectives questioned her and took her DNA and fingerprints before forensically scouring the scene. There were concerns that Le Mesurier had also been murdered by foreign agents, like the Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi a year earlier, almost to the day.

As the news of the 48-year-old's death broke around the world, lots of people - including many friends and associates - assumed he had been murdered. The White Helmets were a thorn in the side of the Syrian and Russian governments, bearing witness to the bombing and killing of innocents and posting the videos online.

In Moscow the television news described his death as a "purely English murder" claiming he had been finished off by his "MI6 handlers" when he stopped being useful. Syria's President Bashar al-Assad later gave an interview where he likened Le Mesurier's death to that of Jeffrey Epstein, saying both men knew too many secrets to be allowed to live.

The British government was quick to dismiss such allegations.

"The Russian charges against him that came out of the Foreign Ministry that he was a spy - categorically untrue," said Karen Pierce, the UK ambassador to the UN. "He was a real humanitarian, and the world and Syria in particular is poorer for his loss."

Digging into his past it seems that at one point Le Mesurier did want to be a spy. After leaving the army he applied to join MI6 and - on paper at least - he looked a perfect fit. He aced the application process, but he was turned down at vetting; it took him months to recover from the disappointment.

An old friend, Alistair Harris, describes Le Mesurier as "Lawrence of Arabia-esque" - an image friends say he liked to cultivate. He had a taste for the finer things in life, and lived in a series of homes on islands. During several years living in the Gulf, he would regularly travel into town from his home on Futaisi island, Abu Dhabi, standing at the wheel of a boat wearing a suit and brogues, his tie flapping in the wind. But he was never in the Security and Intelligence Services says Harris, a former UK diplomat who worked with Le Mesurier on several projects in the Middle East.

The son of a decorated colonel, Le Mesurier earned a degree in international politics and strategic studies before graduating top of his class from Sandhurst military academy. Friends from that time describe him as an incredibly talented soldier, head and shoulders above the others in strategy and communications but "too much of a nice guy for anyone to begrudge him it".

He spent the next decade in the Army but left after becoming disillusioned with the failures of the West to prevent atrocities in Kosovo, where he served as an officer. By 2004 he was working as an adviser to the new Iraqi government, but again he became exasperated by what he saw as wasted opportunities and money squandered on projects which failed to rebuild the country or win the support of its people.

So when, in 2011, he was invited by Alistair Harris to move to Turkey and manage civil society projects across the border in Syria, he jumped at the chance. A democratic uprising, which the Syrian government had attempted to crush by force, had become a civil war, and government-run services were absent in rebel-held areas.

As head of the Istanbul office of Harris's organisation, Ark, one of the projects Le Mesurier's took on focused on training young Syrians to act as firefighters, ambulance drivers and rescuers. Young men and women were already rushing in to help their relatives and neighbours whenever a bomb landed on a residential area, flattening apartments and trapping the residents inside - but often without the necessary skills.

Le Mesurier felt that here at last was an inspiring Western-funded project. In a dark complex war, these were heroes: local people, instinctively trusted by their own communities, doing what they could in a time of crisis. He brought them all together in one organisation and got them professionally trained by the Turkish earthquake rescue specialists, Akut.

White Helmets in training in Idlib (September 2016)

One of Le Mesurier's colleagues at Ark, Shiyar Mohammed, remembers that before this vital training, volunteers would rush into a bomb site wanting to help, but without any idea what they were doing - which sometimes made things considerably worse.

"They hadn't even heard of things like maintaining an open airway," says Mohammed. "Somebody with a neck injury would get picked up from his arms and legs and put on the back of a pickup truck."

Le Mesurier and his team pulled in funding from the British, French, Dutch, Japanese, German and Canadian governments: one of his talents was persuading diplomats to part with their country's money.

Once the trainees returned to their neighbourhoods with their new civil defence skills, Le Mesurier began securing funding for equipment - shovels, medical supplies and hard hats. There weren't enough of the red helmets meant for firefighters, so they ordered white ones - and these helmets would eventually earn the rescuers their nickname.

A White Helmet walks past the remains of a blasted building in al-Kalasa district of Aleppo (June 2016)

But at Ark the White Helmets were just one of many projects and Le Mesurier wanted to focus on them exclusively, so in 2014 - with Harris's blessing - he set up his own not-for-profit organisation, Mayday Rescue.

Speaking to the BBC in 2014, Le Mesurier described the rescuers as ordinary people: "Former bakers, former builders, former students who... chose to stay with very little equipment, and at the beginning with no training whatsoever, to respond to bomb attacks, respond to shellings and to try to save their fellow Syrian civilians."

While rescue operations were taking place in Syria, Le Mesurier was in Istanbul, hundreds of miles away. The only way he could find out what was happening on the ground was by watching videos of the new trainees in action. So he equipped the White Helmets with Go-Pro cameras attached to their hard hats.

Before long, films of the White Helmets' daring rescues were going viral on social media. You can still find them on their Facebook page: hundreds of videos showing men and women in fleece jackets digging, sometimes for hours, through rubble and blocks of concrete, to the sound of cries from those trapped below. Often they pull out corpses - many of them dead children, whose parents are seen wailing over their tiny bodies. Sometimes they manage to pull people out alive, dusty and blood-splattered, who are rushed into ambulances.

White Helmet volunteers carry out a dramatic rescue of a girl trapped under rubble in 2017 in Damascus

Much of the footage showed the destruction caused by Syrian and Russian war planes. The Syrian Air Force's weapons of choice were oil barrels stuffed with explosives - barrel bombs - which were dropped from helicopters on to rebel neighbourhoods. Occasionally the rescuers themselves can be seen weeping - a reminder that they are local people and that the victims were probably people they knew.

One incident in Aleppo in 2014 was filmed in detail: It's night and a lot of people are panicking, frantically digging for their neighbours who are buried under concrete following an aerial attack. A woman caught in the rubble is rescued relatively quickly, but her two-month-old baby is still trapped under layers of debris.

The White Helmets are filmed removing the concrete piece by piece until they can see the baby's head, but they continue to dig until finally they can access the baby's body and a rescuer called Khaled Omar Harrah is able to pull him out, external.

"We saved a baby. It was an incredible accomplishment for all of us," says Shiyar Mohammed. He remembers it as a moment of elation, feeling that all their hard work and the training sessions had been worth it. But their joy was tempered by the realities of war.

"This was just one baby out of thousands and thousands of other babies who have died, who couldn't be reached," he says.

Khaled Omar Harrah died in an air strike two years after rescuing this baby

That scene of the baby's rescue had a huge impact in the West. It was the first time that a lot of people had seen the work of the White Helmets, and many were very moved.

Le Mesurier explained to the BBC that Khaled was a former painter and decorator, external, who became a civil defence volunteer after his own street was heavily bombed. The baby was under seven feet of concrete and the rescue took 19 hours to complete. "The work that they do is absolutely humbling," he said.

But for cynics, the baby-rescue drama seemed a little too slick. Could the whole thing have been stage-managed by Le Mesurier and the White Helmets to gain support and extra funding, they wondered? And in some more radical circles - where everything financed by the West was seen as tainted by an imperialist agenda - the White Helmets started being accused of producing propaganda to push for intervention in the war.

The videos were not stage-managed but the rescuers were deliberately documenting what they believed were war crimes, including the indiscriminate bombing of civilian apartment buildings, markets, schools and hospitals. And while the White Helmets were not calling for Western boots on the ground, they were pushing for the declaration of a no-fly zone enforced by foreign governments.

There is also no doubt that the videos were tremendously helpful for fund-raising.

By the time a Netflix documentary about the rescuers won an Oscar in 2017 Le Mesurier's organisation, Mayday Rescue, was receiving millions of dollars from states around the world including the USA, France, Britain, Germany, Holland, Japan and Qatar. The money was used to run training camps for the rescuers and to send equipment across the border into Syria, including fire trucks and ambulances.

But the Syrian and Russian governments insisted that James Le Mesurier and the White Helmets were manipulating the truth. According to their account the Syrian state, with Russia's help, was protecting a loyal and grateful population from evil jihadists, some of whom were dressed as White Helmets.

The Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad repeated these accusations in televised interviews and Russian diplomats began publishing what they said was evidence of the White Helmets using film sets to produce faked rescues. Two injured children - Omran and Aya - found themselves at the heart of this upside-down story of the war.

In the summer of 2016 a Russian bomb fell on the Al-Qaterji neighbourhood in rebel-held East Aleppo. When it exploded it took out the home of the Dagnish family.

When the White Helmets arrived on the scene they pulled five-year-old Omran from the debris along with his parents and baby brother. His older brother didn't survive.

There's footage of little Omran, being carried by a White Helmet and put into the back of an ambulance. He's tiny and monochrome - covered head to toe in brick dust like a little grey ghost. He sits there, expressionless, utterly dazed.

Omran's photo was on the front page of newspapers around the globe.

Another child whose face appeared on our TVs here in the West, was a little girl called Aya. The eight-year-old was filmed in a hospital in Homs, in western Syria. She had been hiding under a table when the ceiling of her home collapsed on her.

A week after Aya's story was broadcast on CNN, external, the Syrian president gave an interview to Swiss TV where he was confronted with a photo of Omran. Unflustered, he replied that Omran and Aya were just props, siblings being used by the White Helmets in fake videos. And he claimed the rescuers had used them not just once, but several times in different videos.

When journalists (including Channel 4, external and France 24, external) looked into the claims, they found that they were false. Aya was confused with another child, pictured in the arms of three different people, but that was at a single rescue event where the pictures were taken moments apart. Journalists also tracked down witnesses, including Omran's father, who confirmed they had been involved in real bombings.

Facebook post claiming a fake rescue

In another "discovery" of fake videos, the Russian Embassy in South Africa tweeted a photograph purporting to show the White Helmets mid-shoot, external, with dressing rooms in the background and a clapper board in front of the camera. The photograph was quickly identified as having been lifted from the set of a real film, called Revolution Man.

A still from the Revolution Man film's website

In a bizarre twist, the feature film, financed by the Syrian Ministry of Culture, was about a corrupt Western journalist who travels to rebel-held areas of Syria and finds himself helping the White Helmets to fake videos. The White Helmets in the photograph weren't actors working to discredit the Syrian state, they were actors working for the Syrian state.

What the Russian and Syrian governments say about the war is unlikely to have much influence on most people in the UK, but they are not alone in spreading these stories about the White Helmets - a network of sympathetic Western bloggers and activists have amplified their ideas. The most prolific among them is Vanessa Beeley, a British diplomat's daughter who quit her job in manufacturing about a decade ago in order to highlight what she saw as injustices in the Middle East.

Beeley began travelling to Gaza to report on the suffering of ordinary people there. She set up a citizen journalist blog and began posting articles about what she saw. When the war in Syria began in earnest she, along with a small group of other pro-Palestinian activists, became convinced that the uprising had been instigated by Western proxies.

She soon turned her attention to the White Helmets, accusing the organisation of being a Western-created disinformation operation masterminded by a British spy - James Le Mesurier. She took up the allegation that they were faking videos, and also put great emphasis on the idea that they were jihadists, who had been taking part in executions.

The Syrian state granted her visas and offered her government-guided tours of recently captured areas, where Islamist logos on the walls of White Helmets premises were pointed out to her.

What Beeley's videos show is evidence that a variety of groups, some of them jihadists, have operated in the same areas as the White Helmets and possibly used the same buildings - not that the rescuers and Islamists ever worked together.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Nevertheless, there are other photographs and videos online that seem to show individual White Helmets supporting jihadists - from the so-called Islamic State group or the al-Nusra Front (al-Qaeda's representatives in Syria) - either cheering their arrival in an area, or appearing to assist in an execution by removing the body afterwards.

"There's no way to deny it," says Nur (not his real name) who helps manage the White Helmets' media online. "Former volunteers were in pictures waving flags."

In the early days, in a few isolated cases, rescuers joined the White Helmets having left jihadist organisations, he says. In other cases individuals might have seen the jihadists as a possible solution to the bombs that were raining down on them from Syrian government aircraft - but he says the organisation quickly sacked anyone who showed such sympathies. Le Mesurier helped put a code of conduct in place which required independence from all armed groups, among other things, and all the rescuers were trained to understand its importance.

As for the executions, Nur explains, one of the jobs of the White Helmets is to replace undertakers in rebel-controlled areas. "Someone has to respectfully deal with the bodies and get them to their families," he says, adding that they were just informed when and where an execution would take place

The White Helmets say their impartiality and adherence to humanitarian principles has been the secret to their survival as an organisation through so many years of war and in so many different areas with different groups in control.

White helmets rescue an injured fighter in a Damascus suburb in 2017

"There have been multiple different examples of White Helmets teams, responding to buildings, not knowing who is trapped inside, and they continue regardless," James Le Mesurier told Dutch TV in 2015, external.

"They have rescued regime soldiers from under piles of rubble, and they do so neutrally and they do so impartially. For them what is important is saving a life. It doesn't matter who that life belongs to."

One video in 2016 left the White Helmets wide open to Vanessa Beeley's accusations of fakery.

The mannequin challenge was an online fad where people pretended to be mannequins - frozen mid-action before suddenly starting to move, like a mannequin coming to life. The White Helmets had filmed a mannequin challenge of their own. In it they are frozen mid-rescue about to pull a young man out of the rubble. For their detractors this was further proof that the organisation were expert fakers.

Speaking on the Russian state-funded channel Russia Today (RT), shortly after her first visit to Moscow, Vanessa Beeley called the video bizarre. "Whatever reason the White Helmets had for doing this extraordinary event, we've seen a reaction that I believe… massively backfired on them," she said, adding that the stunt made a mockery of the suffering of the Syrian people.

Find out more

When the whole scandal broke James Le Mesurier was furious. His wife, Emma, says she had never seen him so angry.

"He just thought it was the most stupid own goal. James was very frustrated because this would keep getting used and recycled on a routine basis by the White Helmets' antagonists."

I managed to track down the young Syrian who filmed the video. He wasn't a White Helmet - he was a media activist. He hoped the mannequin challenge might help people in the West connect to what was going on in Syria. It never occurred to him that it would be used as proof that the White Helmets' videos were fake.

Vanessa Beeley is so convinced that the White Helmets are working for Western intelligence (and with Islamist militant groups) that she has even argued they are legitimate targets for the Syrian military.

"The White Helmets cannot be considered a humanitarian organisation, when they are embedded with a designated terrorist organisation al-Qaeda, and of course, ISIS and various other armed groups... They do not behave in any way like a humanitarian organisation inside Syria, and therefore… they themselves are a legitimate target in a war situation," she said in an interview to UK Column News in October 2020, repeating a view she had expressed before.

James Le Mesurier was horrified when he saw her tweet this idea, external.

"I don't really have words for it. It was clearly legitimising the targeting of civilians," says his wife, Emma. "And the fact that Beeley was a UK national, and was hosted on Russia Today as an independent investigative journalist, put them at even greater risk."

Vanessa Beeley taking part in a joint Russian and Syrian presentation at the UN in December 2018

Even before Vanessa Beeley's comments, Syrian and Russian states had begun employing double and triple-tap strikes in what appear to be deliberate efforts to bomb the rescuers. After a bomb falls the planes circle around waiting for the rescuers to arrive at the site before bombing a second time and sometimes delaying again before bombing a third time. Almost a quarter of all the White Helmets - there were around 4,300 at the height of the war in 2016/17- have been killed or seriously injured in the course of their work; it's one of the most dangerous jobs in the world.

But perhaps Vanessa Beeley's most bizarre claim is that James Le Mesurier was involved in an organ-harvesting racket. In 2018 she was invited to speak at a joint Russian and Syrian presentation at the United Nations, external, sharing the floor with a Russian researcher.

Apparent witnesses were shown in videos being interviewed by the researcher and saying that they had seen the White Helmets return the bodies of injured victims back to their families with all their organs missing. It is impossible to know whether the people who provided these accounts were speaking freely, and no other evidence was presented. The White Helmets say they have never heard any such claims from anyone in the areas where they operate.

White Helmets investigate a collapsed house in countryside west of Aleppo in February 2020

The accusation that Le Mesurier was involved in murder and organ theft might sound far-fetched but the fact that the ideas were presented at the UN gave them the veneer of officialdom. Misinformation about the Syrian war has become so ubiquitous it has resulted in what psychologists have called the "illusionary truth effect" where most people end up absorbing some of the false narratives, even on an unconscious level. When I first began looking into the White Helmets I had a feeling they were a bit dodgy, but I wouldn't have been able to tell you why or where I had heard that.

All this was beginning to have a real effect on Le Mesurier. At one point, his colleagues say, when he tried to open a new bank account he was turned down because of concerns he might be involved in organ-trafficking. His wife Emma says he worried that after the war was over his reputation might be so damaged that he would never work again.

Vanessa Beeley has denied being pro-Assad despite singing the praises of the presidential couple and the Syrian Army on social media. These days she lives in Damascus and drives around the city in a bright pink 1970s VW Beetle with a picture of Bashar al-Assad pasted in the back window.

The pink VW with a portrait of Bashar al-Assad in the rear window

She declined to give me an interview but we did exchange emails. She told me she is not incentivised by any government, that she is self-funded and that her concern is getting to the truth. She also made it clear that she believes the BBC is a mouthpiece for the British government and is engaged in deliberate anti-Assad propaganda.

Beeley sometimes claims to have been a finalist for the prestigious Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. But when I contacted a member of the prize committee, James Fox, he told me: "There are no finalists of the Gellhorn Prize for Journalism, and no 'runners up'. The prize does not draw up or publish such a list. The judges publish only winners or special commendations."

There are other British Assad sympathisers. One is Peter Ford, the UK ambassador to Syria from 2003 to 2006, who says the White Helmets have faked all but a handful of rescues, have been involved in beheadings, and played a crucial role in the faking of chemical attacks - all of which he believes were hoaxes. He argues that the Syrian revolution was instigated by Western governments with the intention of toppling President Assad.

Ford co-chairs the British Syrian Society with Assad's father-in-law, Fawaz Akhraz, who lives in London and has recently come under US sanctions as one of the state's "enablers… in perpetuating their atrocities". These days the organisation is seen by many as a propaganda operation for the Syrian leadership, though Peter Ford is at pains to make it known that he isn't paid by the society. He has also made it clear he believes the BBC was commissioned "by Le Mesurier's handlers" to whitewash the White Helmets.

Peter Ford is a former UK ambassador to Syria

Ford has shared a platform with The Working Group on Syria Propaganda and the Media, led by a group of British professors from some of the country's top universities, which also argues that chemical attacks in Syria have probably been faked.

In 2020 three members of the Working Group gave a presentation at Portcullis House, external, part of the Houses of Parliament complex, focusing on a chemical attack in the Damascus suburb of Douma in April 2018. It argued that dead bodies and gas canisters had been moved and manipulated in photographs that had been presented as evidence of a chemical attack, and that this staging would have required the active participation of the White Helmets.

The Douma attack is one of the most contested events in the Syrian war, with both the Syrian government and their Russian allies claiming it was a "false-flag" attack, perpetrated by the rebels against their own side, so that the Syrian government would be blamed - and on this occasion the US, France and the UK did in fact respond with a punitive missile strike.

(In the view of the Russian and Syrian governments, all the chemical attacks Syria has been accused of are Western-sponsored fakes. The Russian Embassy in London says the White Helmets "have performed a number of cynical actions, external aimed at discrediting the Syrian authorities and promoting the Western narrative centred around a regime change in Damascus. This includes fake and false-flag chemical attacks.")

An investigation into the Douma incident, external by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) concluded - in characteristically careful language - that there were reasonable grounds to believe chlorine gas was used and that it was delivered from the sky, which would indicate it had been dropped by Syrian or Russian government forces, as no other parties to the conflict possess aircraft.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But two members of the OPCW investigation team rejected this report, alleging that the US had pressured the organisation to reach this conclusion. They questioned whether the limited amount of gas that had apparently been dropped would have killed people where they lay, and also whether the canisters could have crashed through a concrete ceiling without showing more damage. The OPCW said these former employees had not been involved in the full investigation and had not had access to all the facts and independent reports. Despite this, the Working Group found the whistleblowers' arguments convincing - but then had to explain how the more than 40 victims who had been filmed at the location of the attack had died at the same time from the same cause.

One of the Working Group's members, Prof Paul McKeigue of Edinburgh University - whose area of expertise is genetic epidemiology and statistical genetics - suggested that the most likely scenario was that the victims had been executed in a gas chamber and then carried to the apartment building and posed to look as if they had died there.

I contacted the spokesman of the Working Group - a former professor from Sheffield University, Piers Robinson - who told me they did not accept that their assertions were conspiracy theories. He said their output was objective and rigorous and that they consulted widely when expertise outside their own research areas was needed.

James Le Mesurier's wife, Emma, says attacks like these made during his lifetime were putting him under a great deal of stress.

She believes it is likely that he was also suffering from trauma after years of watching distressing videos of the White Helmets' rescues. Most of those they pulled out of the rubble were already dead, including a disproportionate number of children.

In making the podcast series Mayday I ended up watching dozens of these videos - there are hundreds on their Facebook page. This stuff sticks with you, and it left people like Le Mesurier's colleague at Ark, Shiyar Mohammed, traumatised.

"Because I was subjected to so much graphic footage and so much violence. I ended up with sort of basically horrific scenes stuck in my head. Instead of the victims, I'm imagining myself to be in their place," he says.

There was a macho culture, Mohammed says, in which Le Mesurier and his colleagues saw themselves as too tough to be affected by all the horror of the war. Mohammed admits he was naive. By the time he left Ark he was no longer able to function in his daily life, suffering from panic attacks for three or four minutes every couple of hours.

How close was Le Mesurier to experiencing this kind of trauma? I asked Emma about that and instead of answering me she showed me the photos and videos he had on his mobile phone when he died.

There are happy times at home on Buyukada island, hanging out with his dog Balloo, and weekends spent entertaining his two young daughters from his previous marriage. But interspersed with all these domestic scenes are images the White Helmets sent him, of tiny shroud-wrapped dead children, videos of parents wailing over corpses, a lot of horrifying images of cruelty and death.

And it wasn't just the horror of the war - it was the denial of all that horror that got to him. The Syrian and Russian governments were flipping everything on its head, as he saw it, and turning the war's heroes into villains.

That's why, among all those awful images on Le Mesurier's phone at the end of his life there were also countless screenshots of online messages doubting whether any of it was true and calling him a liar, an organ harvester and a jihadist.

In the end, though, it was misinformation from inside his own organisation that was apparently the final straw.

Although Le Mesurier excelled in wooing donors, finances proved to be his Achilles' heel. He had never been across the books at Mayday Rescue, which was dealing with tens of millions of dollars a year - he left that to his colleagues. And it was the financial fallout following a major rescue mission that proved his undoing.

James Le Mesurier (right) with the leader of the White Helmets, Raed Salah

This time the people being rescued were the White Helmets themselves. In the summer of 2018, rescuers in the south of the country were caught between President Assad's forces and the Islamic State group.

In a daring plan dubbed Operation Magic Carpet Le Mesurier organised the evacuation of 800 White Helmets and their families through three border crossings into Israel - a country which had been at war with Syria for decades. To make this happen he helped orchestrate high-level discussions with the governments of Canada, Britain, Germany and the Netherlands, as well as Jordan and Israel. The discussions continued at his and Emma's wedding, attended by some of the key players - a detailed plan was cooked up among the canapes and lamb shanks.

Emma crafted a clever seating arrangement for the reception, grouping together people who needed to speak to each other. Five days later, Le Mesurier flew to Amman, Jordan, to help oversee the huge operation. He was in his element - all his talents in strategising, learned at Sandhurst and honed over his decade in the military, came into play.

White Helmets and their families had been hiding for days in a town near the razor-wire fences and concrete watch towers that marked the disputed border with Israel on the Golan Heights. They had fled their homes as the Syrian military advanced on their towns. Fear of arrest and torture - they had seen videos of "confessions" colleagues had been forced to make - had them running with only the clothes on their backs, carrying crying, hungry children.

Le Mesurier was determined to get them out. Finally, on 21 July 2018, just as the sun was setting, the Israeli military cranked open the huge metal gates at two of the border crossings to let the families through.

A Russian airstrike inside Syria, seen from the Israeli Golan Heights on 23 July 2018

It had taken just a few weeks to mobilise the huge international operation but it wasn't fast enough. One exit route had already become too dangerous - in the previous days it had fallen under the control of Islamic State - and half of those they hoped to rescue didn't make it out. It is not clear what happened to these 400 people, but they were advised to burn their uniforms and hide. Senior members of the White Helmets told me they believe many of those left behind were captured and tortured or killed.

Le Mesurier had managed to save 400 White Helmets, but at a huge political cost. Now he and the whole organisation appeared directly connected to Israel and his detractors - ever prone to see conspiracies involving the hidden hand of Zionism - had more fuel than ever.

"It was extremely frustrating, not just that there was this relentless personal attack on him, but that some people would believe it. I remember him saying, 'Will I ever work again after this?' So I think it was a huge strain on him," says Robin Wettlaufer, then Canada's Special Representative to Syria and one of the people who made the rescue happen.

Le Mesurier returned to Istanbul utterly depleted. He hadn't slept for days and in this exhausted state he made a fatal mistake.

To cover any expenses during the rescue mission Le Mesurier had withdrawn $50,000 in cash from Mayday Rescue's safe. In the event, he only spent around $9,000. Months after his return to Istanbul his head of finance, a Dutchman named Johan Eleveld, asked where the remaining cash had gone. James Le Mesurier couldn't remember.

"He might have lost it, he might have left it at the airport. He couldn't remember," admits his wife Emma. "James had made a mistake."

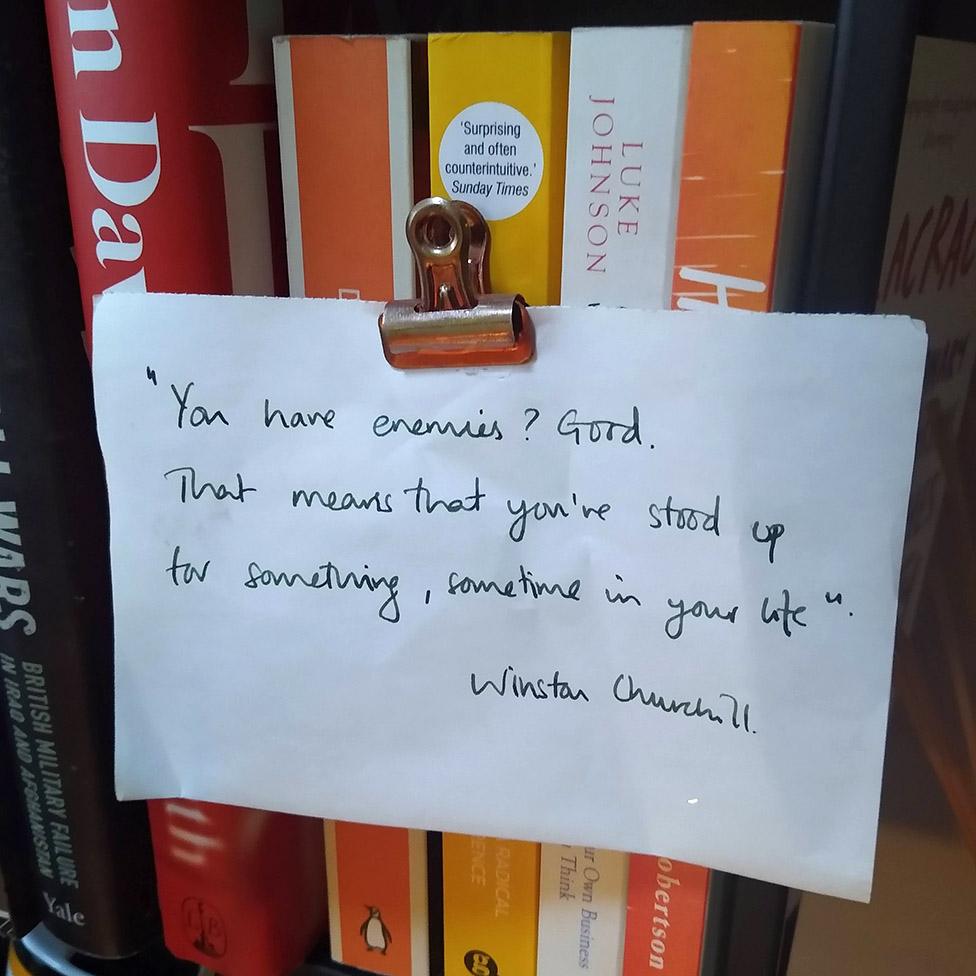

A bookshelf in Emma Winberg and James Le Mesurier's home

He would make an even bigger one. At a meeting with several senior staff members, including Eleveld, Le Mesurier took the decision to repay the missing cash out of his salary. But fearing he would look unprofessional if he publicly admitted he had misplaced such a large amount, he also decided to fake a receipt making it look as if he had replaced the unspent cash as soon as had returned from Jordan.

In November 2019 an audit firm was checking operational changes at Mayday Rescue, with Johan Eleveld assisting them with their work. At some point they turned their attention to the organisation's cash books and came across the faked receipt. When they questioned Le Mesurier about it he immediately confessed. The audit firm also flagged loans and advances that had been taken by his wife, Emma, and warned Le Mesurier that he was leaving himself open to some difficult financial questions.

Emma Le Mesurier says that their relationship with Johan Eleveld had been deteriorating for some time and he was avoiding their calls. Meanwhile, colleagues at Mayday Rescue say Eleveld was telling them the loan Emma had taken, which she had paid back within days, and the faked receipt amounted to fraud - and that there was a high chance Le Mesurier would face a prison sentence.

Johan Eleveld said a non-disclosure agreement prevented him from talking to me, but in an email he denied saying that James might be jailed.

Two nights before his death Le Mesurier wrote to the governments supporting the White Helmets saying that he took responsibility for any financial wrongdoing and offering to resign. The donors did not accept his resignation but said they would need a forensic audit and that would involve freezing Mayday Rescue's operations until a full investigation had been concluded. This meant the White Helmets' salaries, training and equipment would be withheld at a time when they were facing an escalating bombing campaign.

Emma says Le Mesurier spent three tortured days believing that a stupid mistake he had made would result in harm and suffering to the most vulnerable people in Syria - those he had spent years trying to protect.

He also believed that he would be publicly humiliated, and thought it was true that he might go to prison.

Perhaps after years of fighting an increasingly personal disinformation campaign and seeing the brutality of war close up, James Le Mesurier was too tired to fight any more.

The couple spent the evening of 10 November in their flat above the Mayday Rescue offices in central Istanbul. They had a difficult night. James went to bed and left Emma pacing the flat thinking. Around 04:00 he got up and offered her a sleeping pill and stood by the window smoking a cigarette, waiting for her to fall asleep. An hour later Emma was woken by police banging on her door.

In the end, the Turkish police concluded that James's death was suicide. The detective in charge of the investigation told me a high-tech security system meant no-one else could have entered the apartment, and they found no evidence of a struggle.

Six months later, an extensive independent financial investigation by Grant Thornton would conclude that Mayday Rescue's book-keeping was shoddy - but they could find no evidence of financial mismanagement or fraud by either Emma or James Le Mesurier.

Trawling through years of correspondence, they unearthed emails from Le Mesurier to the finance department in the summer of 2018, soon after he had returned from the rescue mission. It turned out the money had never been missing. The emails show he kept the cash and asked the accountants to offset it from his salary. But he was so tired he had completely forgotten what he had done.

Mayday Rescue went into administration in July 2020 and these days the White Helmets' finances are all managed by an American organisation called Chemonics - but as a commercial operation they charge considerably more for their services than Mayday Rescue did so the White Helmets get less of the funds.

When someone kills themselves, that single act, that one moment in the thousands of moments that made up their life, ends up colouring everything. It inverts their biography so we look back at all they did through the lens of their death. And that is not always fair.

James Le Mesurier was a man who lived several lives. He was a soldier, he was a Middle East traveller and an island dweller, a father and a husband and he was a humanitarian. And, like the people of Syria, he was a victim of disinformation.

These days his wife Emma lives alone in Amsterdam, in an apartment they bought together on an island in the centre of the city. She spends hours sitting by a shrine she has built for James; a photograph of him, holding a bottle of wine with a cheeky lopsided smile, sits on top of the wooden box containing his ashes, surrounded by flowers and candles.

"I talk to him, and he talks back," she says, her voice breaking.

"He was an extraordinarily robust and resilient person. But he was exhausted and we were on the losing side. But I don't want to speculate on what James was thinking [in his final moments]. I don't think anyone has the right to do that."