'I've been listening to 300 vinyl records to get me through lockdown'

- Published

Nearly a year since the start of the first UK lockdown, I've listened to every LP I've ever bought - and found a diary of my life in the grooves.

I'm sitting, typing. The rain spreads across the window in glossy veins. We can't go out, anyway, but the weather adds to the feeling of being stuck. So here I am inside, listening to music so familiar I can hear the next track as the first starts to fade. I flip over the record and reset the needle. And I'm crying. Happy tears... memory tears… tears of gratitude. Because you may be in lockdown but I'm at the gig of my life and all it took to get here was a song.

A year ago, the nationwide order to stay inside, possibly for months, filled many of us with anxiety. But it presented a strange kind of novelty too. As our worlds suddenly got smaller a domestic and creative mania took hold. Cupboards were cleared and musical instruments dragged down from lofts. We needed something to punctuate the oddly blank, possibly frightening, expanse of time fanning out in front of us. Like everyone in March 2020, I reached around for a meaningful self-care project. What is it that I love but never quite do? Can I finally do that thing? And there in my living room my eyes fell upon four shelves containing about 300 records.

I'm going to play them all.

I began collecting music in the mid-1990s, very much the compact disc era. But growing up in a house full of my dad's records I always aspired to the heavy properness of LPs. Long players: grand and immersive with lyrics, artwork and gatefold adventures. They take up more space for good reason; they ask for commitment. If flicking on a Spotify playlist is a snatched bag of crisps, vinyl is a sit-down dinner.

Every record is a door and behind each one is a tunnel to a different time and place

I don't file my records from A to Z. Instead, they are in rough chronological order to make listening more fun. If you've just played Dionne Warwick, you're probably in the mood for more from the 1960s. Ah look, there's Dusty in Memphis. Madonna and Prince: obviously neighbours. And if it's a Blur night it's all back to Pulp's for the after party, right?

So, on 29 March 2020 I pull the fluff from the needle and begin.

I start by writing an entry for each album, external: part diary of family life in lockdown, part trip into the past. The music must fit in with home school and work. My partner and daughter climb on board for the journey too. Keep the words short, I say to myself, and so it begins with staccato optimism. The first few records whizz by as we consume whole centuries in greedy gulps. Mozart, Holst, The Shirelles, Eartha Kitt, The Kinks: from the classical period to the swinging sixties in days.

It feels good to give life at home an ever-changing backing track. Listening makes us look with clearer eyes too and we notice more birds in the trees as we gaze up at London skies without planes. The days are warming up and the music is propelling us forwards.

From Beethoven:

Symphony number three. An injection of gothic drama. We find ourselves singing questions to each other as if in a German opera. "Is the soup ready? Yes. It. Is!"

To The Beatles:

The "blue album" - 1967-70. This feels like a big moment in the journey. It was my GCSE soundtrack. I played it over and over as I revised. We turn it over and play it twice.

For my daughter Frankie the lyrics to I am the Walrus were a revelation

As the weeks in lockdown unfurl, this ritual gives the days meaning and structure, but also a firm connection to the people from whom we are separated. Music seems to be the most direct path to memory, and, on an April afternoon, the sunlit harmonies of Simon and Garfunkel roll me on to the carpet of my childhood living room.

I am back in early 1980s Leeds and my mum is playing Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme. This feels exciting because my dad is the Record Person of the house. The room is bright, the curtains are orangey brown in leaf swirls. I am four and my older sister Claire is eight. Kerstin, my younger sister, is a baby.

I am fitting in albums between calls, cartwheeling into the 1970s from Joni Mitchell, who we play during Easter's mirage of summer, to the Velvet Underground, Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith and Abba. I text my dad about Joni. He says A Case of You is his favourite song. "I love the humour and the way she stretches the notes on 'Oh Canada'…"

Hanging out with my dad's Abba records, aged 19

I'm excited to keep discovering what's next but also obeying my self-imposed rules: no skipping, both sides must be played. Blondie, Bowie, a whole week of Kraftwerk. Onwards into the 1980s, Pet Shop Boys, New Order, Neneh Cherry, De La Soul: a party in my office. And I notice I am writing longer diary entries because the songs are in control.

I am often puzzled by friends and family recalling detailed accounts of things that happened decades ago that I can't remember. Yet here, leaning over the turntable, something's changing. Every record is a door and behind each one is a tunnel to a different time and place. I'm a kid in the living room daring myself to sit beneath my dad's giant booming speakers. I'm a teenager waiting for life to begin. I'm tramping across Glastonbury's shimmering mud plains at 3am. I'm DJ-ing at a party and everyone is dancing.

As I have told everyone all my life, I met The Human League when I was two. Singer Phil Oakey's brother lived next door to my parents in Leeds. My "memory" of seeing his majestic asymmetric fringe up close is now so hard-baked into my brain that I will never know, nor care, about the actual truth. His brother was certainly our neighbour in the early 1980s. In my mind I saw them the night after they were on Top of the Pops, at number one with Don't You Want Me, and they came to our suburban street in a cloud of glitter and hairspray.

The Human League performing in 1987

The fact I have chosen, since very early in my life, to peddle this story, tells you I was born to love pop music. I grew up surrounded by it. My dad has an encyclopaedic knowledge of record labels and even wrote the lyrics to a (now very rare) Merseybeat single. My older sister, with her Prince tapes blasting through the bedroom walls, got me into Smash Hits and then got me, a young-looking teenager, literally into gigs.

But it was my pre-GCSE English teacher, Mr Robinson, who first spotted my love of music and - amazingly, because I was just 14 - entrusted me with typing up a series of sleeve notes to his favourite songs. I created all these booklets on a typewriter and, listening to compilation cassettes as I went, tumbled through a new and sophisticated world from David Sylvian to Virginia Astley, Roxy Music and David Bowie. I switched from Chesney Hawkes to Brian Eno in a Smash Hits backflip one afternoon in 1993.

As I hungrily play through the decades, some records feel too important to throw on the deck without a sense of ceremony. In early May, I reach Kate Bush.

We are nervous about putting on Hounds of Love because it's too good for any old day. We keep delaying until we are in a suitably reverent mood. Side A - Running up that Hill, The Big Sky, Cloudbusting - is perfect and I have to slap myself to stop its brilliant familiarity from rolling too fast.

And then I'm at that concert:

I'm at Hammersmith Apollo, waiting for Kate. Her first shows in forever. The night already feels like a dream lapping into focus and away again. I'm five metres from the front, in a row of weeping grown men. It's one of the most incredible gigs of my life.

Kate wisely banned cameras so my only furtively snapped phone image from the night is of a painted feather, projected onstage before the show began. That feels right for this memory game.

My only photo from the Kate Bush show

Before the internet, the feeling of being "not like these people, here" was a strong, addictive drug that others who grew up in provincial towns may recognise. It is why bands come from the suburbs, or so the theory goes, because boredom makes you creative. I was very lucky to grow up in Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, a pretty market town full of day trippers. But in my mid-teens I craved friends who played guitar, not golf or PlayStation - and then I found Radiohead.

It's dark, there's condensation on the windscreen and we're listening as The Bends crackles in the tape slot of my friend Yorkie's pale blue Mini Cooper. The light beams pick out the drizzle and we flick ash from the windows. Well, Yorkie does: a proper teenage chain smoker who - yes! - plays guitar and always wears Vans. She's into Nirvana, I'm into Blur. We both love Radiohead. It's 1996 and we spend many nights driving around country lanes with nowhere to go but quite sure where we don't want to go: sticky-floored pubs awash with older men trying to snog us.

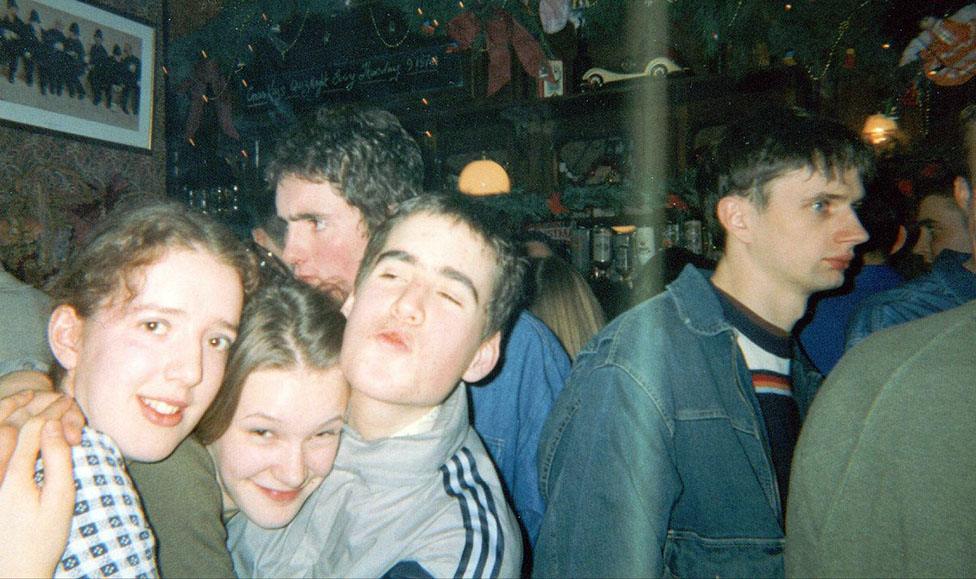

At the pub with my friend, and fellow Radiohead fan, Yorkie

A few months later I manage to persuade my school friends to buy tickets to the Manic Street Preachers at Doncaster Dome. I'm the keen one and so I wriggle my way up to the front row. I've got my spot right in front of Nicky Wire's amp and the lights are starting to dip. The opening chords of Australia boom out and we all sweep as one towards Nicky. My feet lift from the floor. Wire is doing scissor kicks and wrapping a black feather boa around his microphone stand.

There's another surge of bodies. And the next thing I know I'm in a muffled underworld. It's all too quick to panic. I'm just... gone. I wake up some time later and I'm propped up against the back wall of the venue, at least 100m from where I'd been. Motorcycle Emptiness is playing, so we must be near the end of the set. And I look down at myself: I'm covered in black feathers.

I hadn't thought about this experience for years. Playing Everything Must Go brings it tumbling back. I passed out in the crush to grab the feather boa, was rescued by venue staff, and subsequently missed at least half the concert. It's 24 years ago, but I'm there again in the sweat and drama of it all. And somewhere I still have my souvenir - a clutch of Nicky's black feathers.

A Manics front row a few years later - still chasing feathers

At 18, I took it for granted that I'd spend most summers pressed up against the front rails of a massive concert watching an iconic band, singing until my voice went hoarse with thousands of strangers. That's what we did. In these pandemic times the idea feels alien.

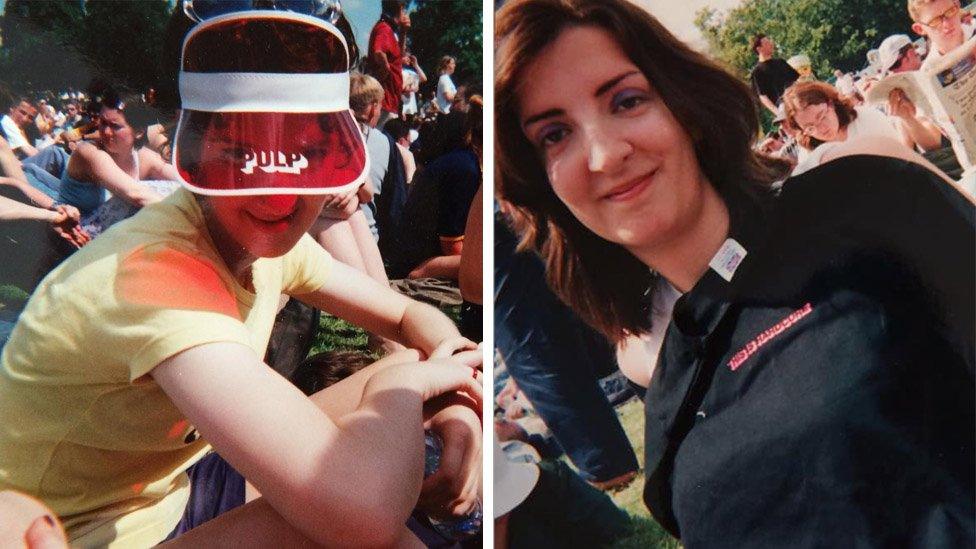

Glastonbury 1998 was a very muddy year but my sister and I didn't let the military camp conditions dampen the party. A local farm boy riding a horse bareback (really) carried in our bags and we were offered acid marmalade before we'd even pitched our tent. It honestly felt like our Woodstock, only I was in Adidas trainers and we'd packed some cheese sandwiches. Friday night: Primal Scream. Saturday night: Blur. Sunday night: Pulp. Some bloke called Bob Dylan played in the afternoon.

It's playing Pulp's Different Class that has sent me spiralling back to the swamp lands of Worthy Farm. I start a late-night WhatsApp chat with my older sister, Claire, and she reminds me that we spent one of our Glasto nights roaming around aimlessly looking for adventure; still buzzing after watching an amazing set from Underworld. It was otherworldly: dotted encampments of firelit raving, as Claire puts it, "floating on vast biblical lands of mud… awesome, epic, a one-off experience and time". I find a clip from that night in 1998 on YouTube and, sitting here at my keyboard in 2021, I fold into an exhilarating happy-cry. And I feel immense gratitude that I was a teenager then.

With my older sister Claire at Pulp in Finsbury Park, 1998

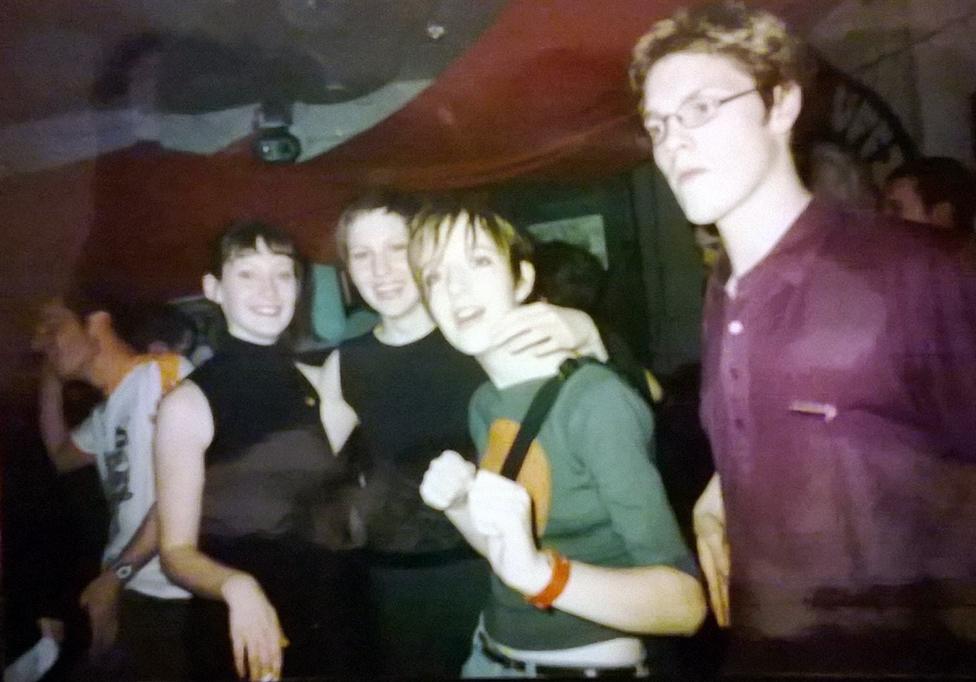

I was in my "Hell is other people" Manic Street Preachers T-shirt at Leeds University's freshers' week that autumn, but it turned out that the Manics (and Sartre) were wrong. I soon found my people. My new friend Rose, who lived across the block from me in Lupton Flats, also loved Blur. And Suede. And Elastica. My friend Marion had even more albums than I did. Debbie, across the way, was already in a band. We didn't care about the squirrel infestation, the wiry brown carpets or the tumble driers that melted people's pants, because we had music.

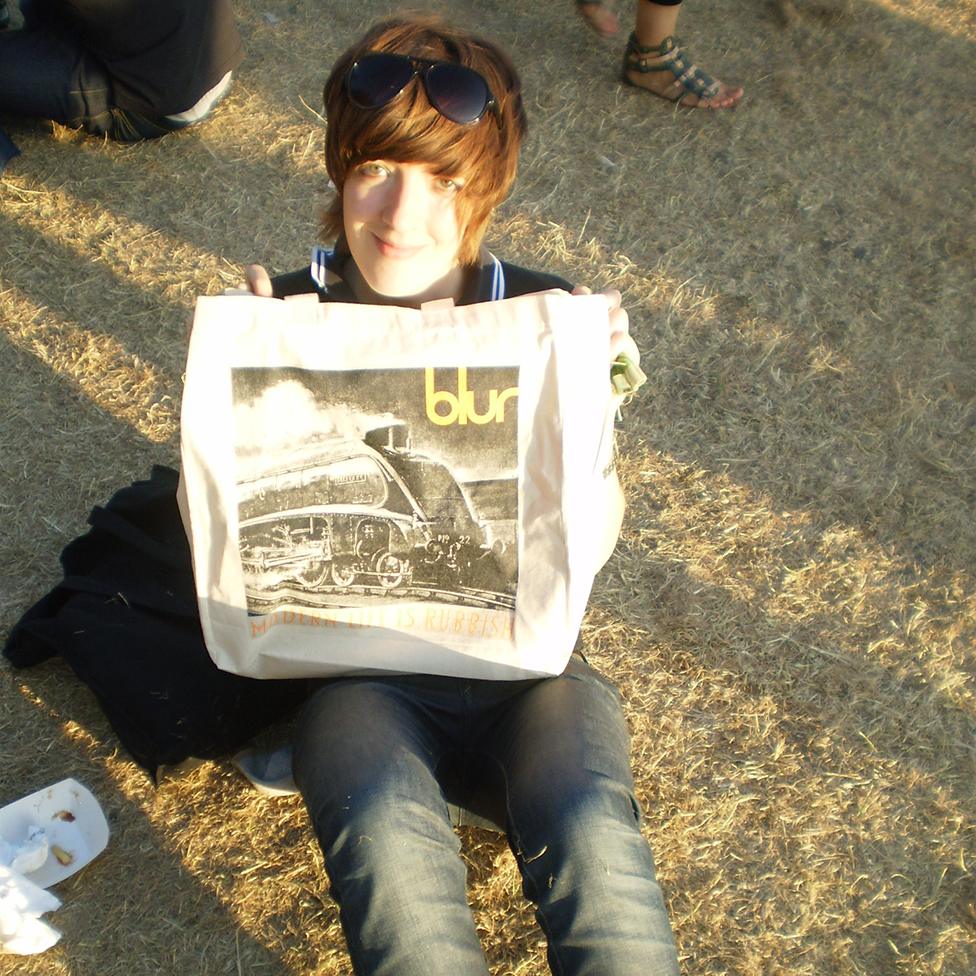

I'm listening to Blur, one of the bands I've most often seen live. I first fell for them aged 16 in a screaming Sheffield Arena. Going through my records I find the tickets from that night in one of the sleeves, along with my coach fare. By the time I got to university, Blur were in their sad ballad phase. Here in the future, playing the mournful but beautiful sixth Blur album, 13, a funny memory pops into my head from that first week in Leeds.

At the student union indie night with Rose, Marion and Andreas in 1999

After going to various indie discos and generally hanging out with my new friend Rose, I realise with horror that I've forgotten her name. I panic and while she is in the loo, I frantically grab her purse from the kitchen table and rifle through for her student card.

Rose! And then she saunters back in.

At university I had the best job, probably ever, writing reviews for Leeds Student newspaper. This meant free music, free gigs and free pizza. I met lots of musicians I loved too, from the Super Furry Animals to Moby, via Stereolab, Goldfrapp and Saint Etienne, my desert island band. It's June 2000, I've just interviewed them, and I'm in the crowd at a sweaty Leeds Met.

Sarah [lead singer] spots me in the crowd and - like something from a movie where, for once, everything comes together - she points and dedicates Nothing Can Stop Us to me: "This one's for Anna!" I remember it vividly because I was snogging a boy at the exact moment.

Albums from the early noughties plunge me back into that nervous time between college and life. But there were joyful times too as I discovered bands like The Strokes. And then met them. An odd claim to fame, but I played pool with lead singer Julian Casablancas for 10 minutes in 2001. I was writing for the student pub magazine, Yellow, at Leeds Festival, and access to our tent became the hottest backstage ticket, precisely because we had a pool table, plus beer and comfy couches.

In stumble The Strokes. Julian shouts, "Who wants to play?" Excitement and nerves suppressed, a rock 'n' roll game kicks off involving me and a couple of other student writers. A few minutes later, Scottish band Mogwai drift over in their tracksuits, climb on the table and pot all the balls with their hands. Ah well.

I've seen Blur live around 20 times

That night The Strokes were bumped up to the main stage, such was the buzz around them, as New York once again replaced London as the centre of the music universe. I had to get myself there - and duly did within a couple of years. Here in 2021, I'm listening to Give Up by The Postal Service for the first time in years. And suddenly I'm messing about in deep snow on Fifth Avenue.

There's been a blizzard and all the actual residents are sensibly indoors. We three Brits are, of course, out in it, making snow angels, dodging a telling off from the NYPD and getting ready for another night at the Red Bench, our new favourite bar in Lower Manhattan. I'm there with Ed and Sarah, the breakfast team from my first job in radio. Give Up is my current obsession. I listen to it throughout the flight, and I'll forever associate these songs with the thrill of touching down on the tarmac of JFK.

Music is the map: the veins along which memories can flow and pump the heart

My journey through music and memory has taken me everywhere during the past 12 months of lockdown. I've been back to school, back to New York. I've spent time with family and friends, despite them being hundreds of miles away. I've danced. I've cried. I've thrown my hands in the air. Even though I haven't seen him for ages, I've felt closer to my dad through WhatsApp chats about Leonard Cohen concerts, the Cavern Club and his love of lyrics. My mum has loyally read every word along the way. And I've been back to the best gigs of my life, felt the heat of the crowd and sung my heart out.

Singing my heart out at an Arcade Fire gig

I know it's all in my head. But isn't that the best thing? Listening to music increases blood flow in brain areas involved in generating and controlling emotions. "Emotional music we have heard at specific periods of our life is strongly linked to our autobiographical memory," explains Lutz Jancke, from the Institute of Psychology at the University of Zurich, in the Journal of Biology. Music also activates imagery in the mind. It's why listening to music every day can help stroke patients recover memories as well as other brain functions.

It's people and shared experiences that make listening to music so meaningful and so loaded with memory and emotion. In a year of separation from our loved ones, how great that music is the map: the veins along which memories can flow and pump the heart.