Piccadilly 1965: How six Indian friends found their feet in the UK

- Published

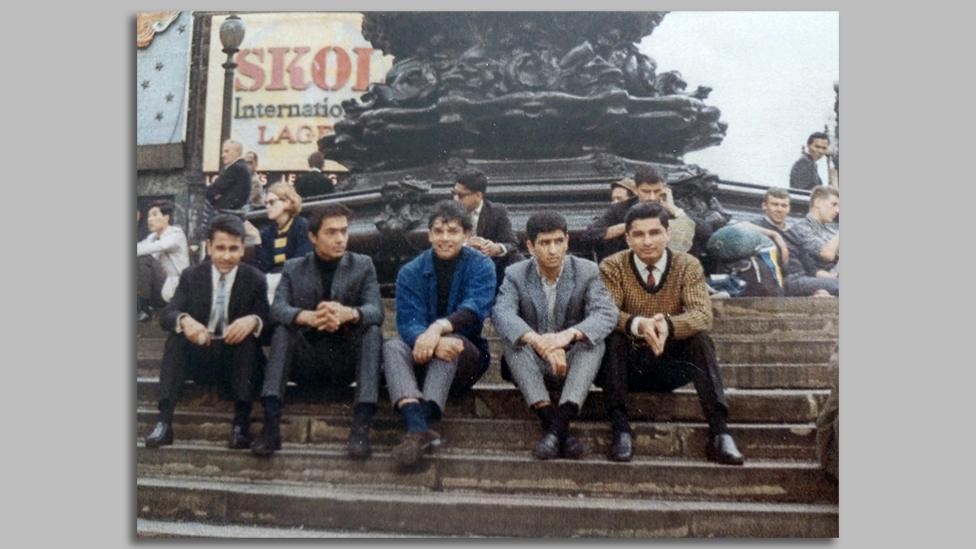

Chandu, Pravin, Praful, Indu and Fazal at Piccadilly Circus

A generation of Indian immigrants from East Africa, who arrived in the UK in the 1960s determined to succeed, are now in their 70s and 80s, looking back on eventful lives. The BBC's Krupa Padhy, whose father was among them, tells the story of Praful Patel and his efforts to find a place in British society.

In 1965, at 21 years old, a despondent Praful Patel made his way to the Central YMCA - the Young Men's Christian Association - on London's Great Russell Street. He was working as a dish-washer but hadn't been able to find rooms he could afford on his wages, so it was almost his last hope.

"They said 10 shillings a week for a centrally heated room in central London," he remembers. "I thought, 'That can't be bad.'"

Before long he had a better-paid job too. In fact, three of them: as a receptionist at Gilda Jewellers in Hatton Garden, as a waiter at the Wimpy fast-food restaurant on Oxford Street and as a barman at the Horseshoe pub across the road from the YMCA.

One evening, as he returned to the YMCA, a group of five young men sitting in the lounge caught his eye. They were Indian, like him.

"To actually walk into an institution in England with all these Indians sitting there and chattering away in Gujarati was wonderful," he says.

He'd never heard his mother tongue spoken with such ease in England.

The men were all roughly the same age - either a few years younger or a few years older than Praful - and they were also from families that had left Gujarat and crossed the Indian Ocean to find work in the British colonies of East Africa. They were among a wave of young people with Indian heritage who were leaving these newly independent nations for the UK, with big plans to work, study and succeed in life.

Praful had only recently arrived himself, but he was unusual in that he had spent much of his childhood in England.

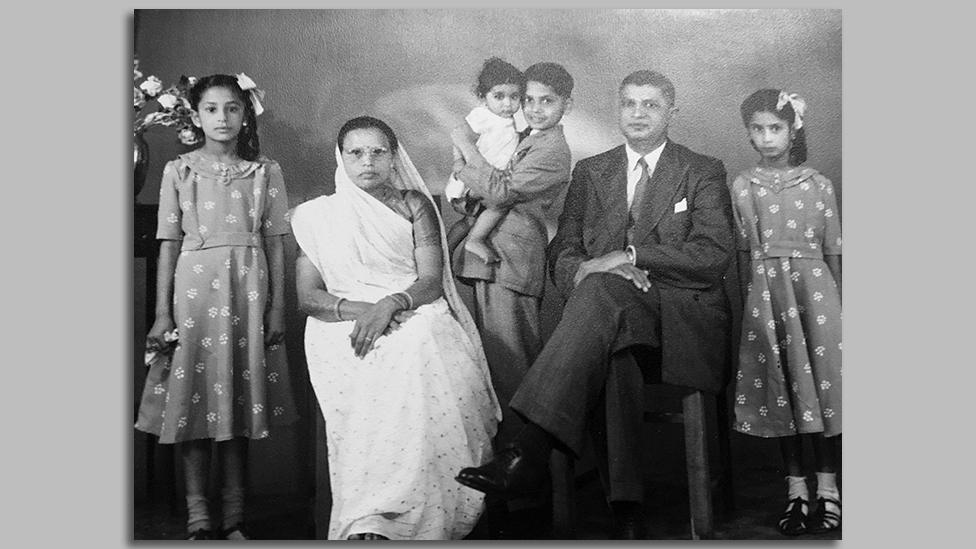

His father, Jethabhai Patel, had emigrated from Gujarat to Kenya as a teenager in the early 1900s and had become a civil servant working on the East African Railway Network. Later elected to the Kenyan parliament, he attended the Queen's coronation in London in 1952.

He was keen for his children to have a British education, so in 1954, when Praful had just turned 10, his father put him on a plane for the 48-hour journey to London.

As Praful bid his tearful mother farewell, he had no idea he wouldn't see his family for another three years. He had never before worn long trousers, socks and shoes, and his English was limited to two phrases - "please" and "thank you".

Praful (right) about to fly to London for the first time

His guardian in England was Stella Monk, who worked for the Empire Day Movement promoting ties between schoolchildren in Britain and its colonies, and she took him to a prep school in Eastbourne. Two other boys named Patel were already studying there, so he was dubbed "Patel number three".

Raised a vegetarian on spicy curry, daal and tender chapatis, Praful struggled with the school's unseasoned boiled vegetables and doused the food with vinegar to compensate - a habit he still has today.

When it came to holidays "Auntie Stella", who lived in a caravan, would arrange for Praful to stay with host families across the country.

One Christmas was spent in a small village in Somerset with a doctor and his young family. Accompanied by a Nigerian boy of a similar age, he'd walk through the village with residents peering at them through the curtains.

"Some people would walk up to us, look at our faces and ask, is this paint?" laughs Praful. "We got invited to every single Christmas party."

The ultimate holiday was Praful's first trip home, three years after his arrival in England. Up until then he had been corresponding with his mother through letters written in his much-improved English - only his mother didn't understand them as she couldn't read or write the language.

But by this time Praful had largely forgotten how to speak in Gujarati.

"My father wanted me to become like an Englishman and in truth I did become an Englishman," he says. "But in my heart of hearts I knew that the English would never accept me fully."

Praful as a child with his parents and some of his siblings

Back in the UK again, Praful was moved to a public school in Sevenoaks, where it was routine for boys to become confirmed into the Christian faith.

Everyone in England called Praful "Praf", so when it was the 14-year-old's turn to be confirmed, that's the name he gave to the priest. "I'm sorry, but that's not a Christian name," came the reply.

"So, they baptised me and then confirmed me on the same day, as Peter," Praful says. It's a name he still often goes by today.

Academically Praful didn't flourish, and after scraping through four O-levels he was summoned home by his father.

Back in Nairobi, he trained to become a teacher. But after a couple of years working in a school, he went to his father and said, "Dad, I don't fit in here. I'm a square peg in a round hole."

Jethabhai paid for a ticket for Praful back to London. And this time it was one-way.

But if Kenya was changing because of the end of empire, Britain was changing too.

Praful noticed that attitudes towards black and Asian people had hardened.

"I went to try and look for a place to live," he remembers. "Walking up and down Notting Hill Gate, trying to find a room for board was just discouraging, to say the least. Every single sign said: 'No coloureds and no blacks need apply.'"

His teaching qualification from a British institute in Kenya wasn't recognised in England, which is why he got a job as a dish-washer - and ended up at the YMCA, where he met the five young Indian men.

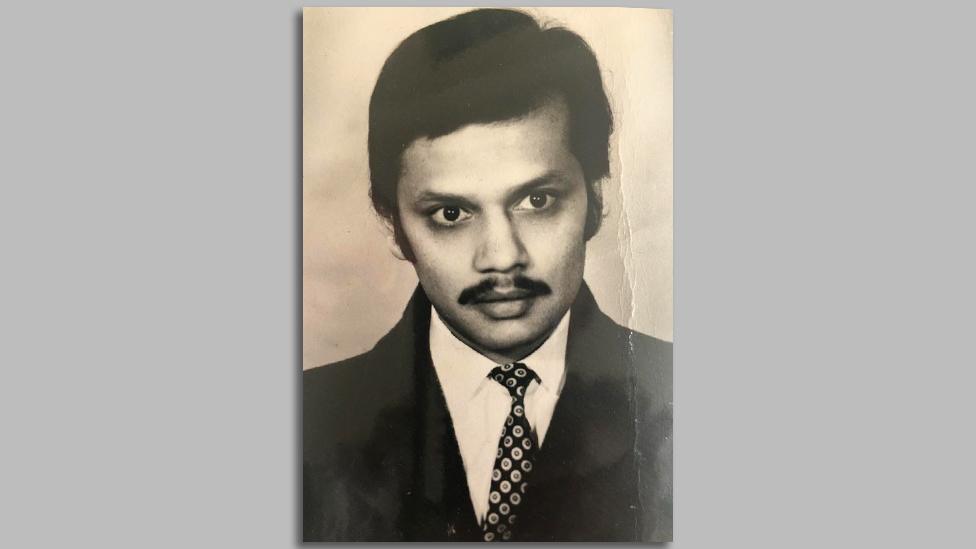

Praful at 23

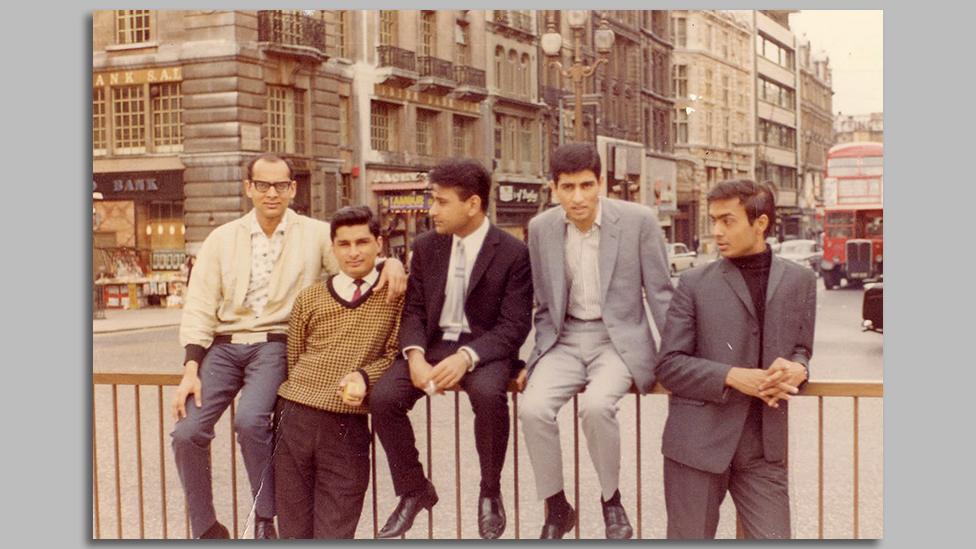

The group went on to become firm friends, one of them being my father, Chandrakant Thakrar, known to his pals as Chandu.

All would make an effort to don their smartest suits and arrange their hair in a perfect quiff, but Praful was one step ahead. It was commonly thought that he was more English than all of the YMCA crew put together.

"The clothes I wore and my mannerisms were very different to theirs. I used to go down to Carnaby Street. I bought purple roll-neck sweaters and Nehru-collared glittery shirts. At the time, these lads were not into that sort of thing. They were much more conservative, having just arrived here.

"They saw me doing things that they'd never, ever dreamt of doing. I mean, I had girlfriends, English girlfriends, and they used to come to the YMCA to meet me. And we'd go out and they'd stand there and they'd look at each other and say, 'Look at him!'"

A common history helped them bond; a childhood growing up under the British empire, a pride in their Indian ancestry and a sense of responsibility for the families they had left behind in those fallen colonies.

All of them came with a fierce work ethic, which they believe they inherited from family elders who had taken the leap to leave India decades earlier in search of economic opportunity.

One evening, in their usual catch-ups in the YMCA lounge, one of Praful's new friends, Indu Mamtora, turned to him and asked, "So Praful, is this it for you now, working as a clerk, waiter and barman? Don't you want to get yourself a professional qualification?"

That was the nudge he needed. With their guidance and encouragement, Praful completed his A-levels and went on to study law at Holborn College - all while holding down three jobs. He eventually joined London's Lincoln's Inn.

The YMCA crew

This photograph was taken by Praful and shows, from left to right:

Champak Panchal - worked as an engineer in the oil industry and emigrated to the US

Fazal Musa - met an Australian woman, moved to a ranch in Australia and fell off the radar

Chandu Thakrar - the oldest of the group, now 80, a retired chartered accountant

Indu Mamtora - a successful lawyer, now sadly dead

Pravin Choksi - a grandfather of five, still working in a London tech shop

Praful's first job after qualifying was at the Treasury Solicitors' department, after a tip-off from Indu. But one day he got a call from the senior solicitor advising him to not work so fast. There appeared to have been rumblings of discontent from old hands, who worked at a slower tempo.

"I didn't want to just sit and let it all drift," he says. "I wanted to be active. So I left the solicitors."

Not able to find a job in law that paid well enough, he moved into management accountancy on my father's advice. From managing the books he went on to handle multi-million-pound contracts, he says, and later tried his hand successfully at sales.

He'd achieved the professional qualifications his father had so longed for him to get - but he often seemed to hit a glass ceiling. Applying for a job at one company he was told he'd have to take English lessons first - which made no sense as his English, learned at public school, was completely fluent. Later the recruiter told him the department was not yet ready for a "black salesman".

"Today, it might be called racism," recalls Praful. "But that's not how I saw it. If I saw an obstacle I had to get around it. I didn't try and break down the barriers of racism because I knew that is par for the course."

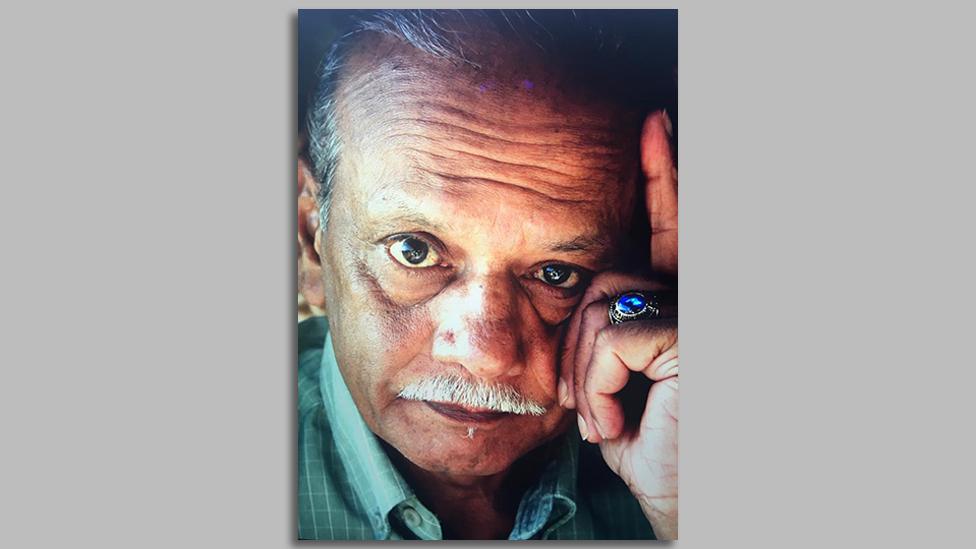

Praful at 66

A similar resilience was shown by others in the group of friends from the Central YMCA. One was Champak Panchal, now a successful engineer living in Texas. After he finished his studies in London, he began his first job at Handley Page Aircraft, only for them to go bankrupt soon afterwards.

Champak was told to sign up for benefits, and turned up at the unemployment office.

"They offered me £2.10. I couldn't survive on that," he says. "I told the guy I was a graduate engineer and I could not accept the money." Instead he accepted their help to find a job, and successfully got a clerical role at a government office.

My own father began managing the books at Central Middlesex Hospital whilst studying for accountancy. He failed his exams a few times but he remembered his father's words, "Chandu will keep knocking on those doors."

Retired now after a successful career, he is still endearingly quick to remind us he is a "chartered management accountant".

Praful with his wife, Lizzie

Those friendships have stood the test of time, despite ups and downs, including such things as illness, financial hardship, and moves abroad.

As for Praful, from his childhood in Kenya, to finding his feet in London as a British citizen, there was nothing predictable about his life trajectory.

"I was taken out of my surroundings in Kenya as a little boy and implanted in England. I didn't have anybody who told me what to do or what not to do. I was a pigeon let out into the air. I just flew wherever I fancied," says Praful. "Yet I love England. It's been uncomfortable at times, but it's home."

In his late 70s, Praful is in remission from leukaemia, and living in the Cheshire countryside with his wife Lizzie.

And after that first trip back to Kenya as a young boy - when he vowed never to forget his mother tongue again - he remains fluent in Gujarati.

Listen to the five episodes of Piccadilly, made by Krupa Padhy for Radio 4, on BBC Sounds

Update 3 June 2021 - After the publication of this story, one of Fazal's daughters got in touch to say that her father had emigrated from Australia to Canada, where he lived with his second wife and children. He died from cancer at the age of 47.

You may also be interested in:

An Indian student won acclaim in Wales as a bard and became the first woman to get a law degree from University College London. And although racial prejudice brought a heartbreaking end to a three-year relationship she never went home.