'How I escaped a hidden world of gangs and exploitation'

- Published

Aliyah

At first glance, Aliyah looks like any other 24-year-old - she loves fashion, posts selfies on Instagram and appears happy. But her smile conceals a background of abuse and exploitation - a pattern that experts warn is all too common among forgotten teenage girls.

Aliyah's earliest memories are not of family trips and teddy bears.

Instead, she recalls coming home from school and feeling relieved if she saw the front window was open. It meant her dad was letting in air.

Aliyah didn't know much about drugs back then. But she'd learned the open window meant he'd be in a good mood: "Whereas if the window is shut there was no smoke, so Daddy doesn't have what he needs," she says.

At the time, no-one outside the family knew what went on behind closed doors in their house in south London. She says there was violence in the household and sometimes it would be inflicted on Aliyah. She and her sister would hug each other on their bunk bed crying themselves to sleep at night.

Aliyah as a child

At times, money was scarce and, as a result, food could be as well - Aliyah recalls days when there was none in the house at all and she'd go to school hungry.

It would be years before Aliyah and her siblings were picked up by social services. Aliyah feels strongly that opportunities for safeguarding her and her siblings were missed - she remembers her parents putting on their "best faces" when authorities came around.

Stories like hers follow a classic pattern, says Kendra Houseman, a consultant in child criminal activity: "If home is not a safe place, that makes them vulnerable to exploitation." And she warns there are many more hidden girls out there like Aliyah.

But against all the odds, Aliyah eventually managed to turn her life around.

One sunny day, when she was eight, Aliyah's dad had friends round to celebrate his birthday. Someone gave Aliyah champagne. She drank so much she had to be taken to hospital with alcohol poisoning.

It was the beginning of Aliyah's descent into alcohol abuse. "After that, I'd just drink - I'd always want to drink," she says. By 13, Aliyah had become dependent on alcohol. "Drink became a problem - I was drinking because I was depressed."

Find out more

Amanda Kirton's documentary Hidden Girls looks at the forgotten world of girls in gangs and the extent to which they are criminally and sexually exploited

Watch on the BBC News Channel at 13:30 on Saturday 2 October or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Her parents' marriage broke down, her father left the family home and over time it became what is known in drug circles as a trap house - a property where drugs and weapons were held, and in which dealers would congregate.

Aliyah remembers being left alone there one time.

"I was 10, left with all these drug dealers in my house," she says. Still a young child, she assumed it was her fault, somehow: "I honestly didn't know what I'd done."

There was one man, a regular visitor at the trap house, who noticed something was amiss. "He showed more genuine care," she says. He would look after Aliyah, became a friend and remains in contact with her to this day. "I think he saw a little girl that didn't have her parents, the way she needed to have her parents, and I think he just wanted to show a bit of support here and there when he could."

Aliyah

But although Aliyah was on the child protection register she was still allowed to live in those circumstances - and Aliyah finds the conduct of the authorities difficult to understand. "I think they missed a lot of things," she says. "In this day and age, if that was going on in the home, the child will be gone straight away."

Eventually, when Aliyah was 12, she was taken into foster care. However, by that time she was already a deeply troubled child.

Aliyah says she was moved between around 20 foster homes over a three-year period. She would run away and sleep rough. She'd drink until she blacked out. At school her behaviour grew worse - she'd break things and bully other children.

She remembers feeling as though she had no way out - that she was existing in survival mode. She self-harmed and tried to take her life on many occasions.

While hanging around with older teenagers, she was drawn into a world of crime, violence and drugs. Aliyah began stealing, robbing and beating people up - the trauma of her childhood had set her on a destructive path, she says.

Aliyah as a teenager

Soon she gained a reputation - if someone in the gang stepped out of line, Aliyah would be the one given the job of punishing them physically.

"It was years of hurting myself and hurting other people," she says. "It was because of what I went through - the things that I didn't deserve to go through, it was affecting me.

"It did rob me of my childhood. It was taken away from me way too young. I couldn't get it back because things just got worse after that."

All this made her a prime target for grooming. Eventually, Aliyah met an older man in his 20s who convinced her they were in a relationship. "I thought I was in love with him," she says.

But the reality was very different. "He had me selling his drugs for him," she says. "I couldn't tell that I was being exploited." Soon enough, they broke up.

Rita Jacobs, a social worker in London, says this "boyfriend model" of exploitation is one that she has observed with increasing regularity.

"Some girls, they are unaware that they are actually being exploited - they do believe that they are in a romantic relationship with a partner, and what they don't realise is that partner is actually a perpetrator," says Jacobs.

Aliyah's grooming took place offline. But Hannah Ruschen, child safety online policy officer with the NSPCC, says that in the decade since, technology has made it even easier to target and exploit vulnerable girls.

According to the charity, 5,441 Sexual Communication with a Child offences were recorded in England and Wales during 2020/21 - a rise of 9% on the previous year and an increase of 69% from 2017/18, when the offence was first introduced.

The NSPCC also says over 80% of children who are groomed online are girls and that most of those children are aged 12-15.

"Because of the way that there's constant access to the child via the internet, it can happen very quickly," says Ruschen. "It can go from a simple act like a friend request and very quickly escalate to the sharing of images online."

At the age of 14, Aliyah ran away from her foster carers. She stayed at various friends' houses. She knew she'd been reported missing so couldn't go out.

Eventually the isolation became too much for her and she handed herself in at a police station. She was given a youth referral order and, for the first time, placed in a care home.

She didn't know it at the time, but this marked the first stage in turning her life around.

By the time she arrived at Bridges Lane, a sprawling building in Croydon, south London, Aliyah was 15. When she arrived, she put on a front, as though she wasn't afraid, but deep down she was - this was a new experience for her.

On her first day, an adult member of staff laid down the rules: there was a curfew and she had to be home on time. Every night all the residents would sit down and eat dinner with care workers.

"She just laid the law down to me and that's what I needed," Aliyah recalls. She'd never experienced discipline before. "I loved it. I just didn't show it, because I didn't trust no-one."

Aliyah had a rocky start at Bridges Lane - misbehaving, seeing how far she could push boundaries. "I think I was testing them, but I was also crying out for help," she says. "I needed a family. I just wanted to just cry and hug someone and I got to do that here. And I met Rowena."

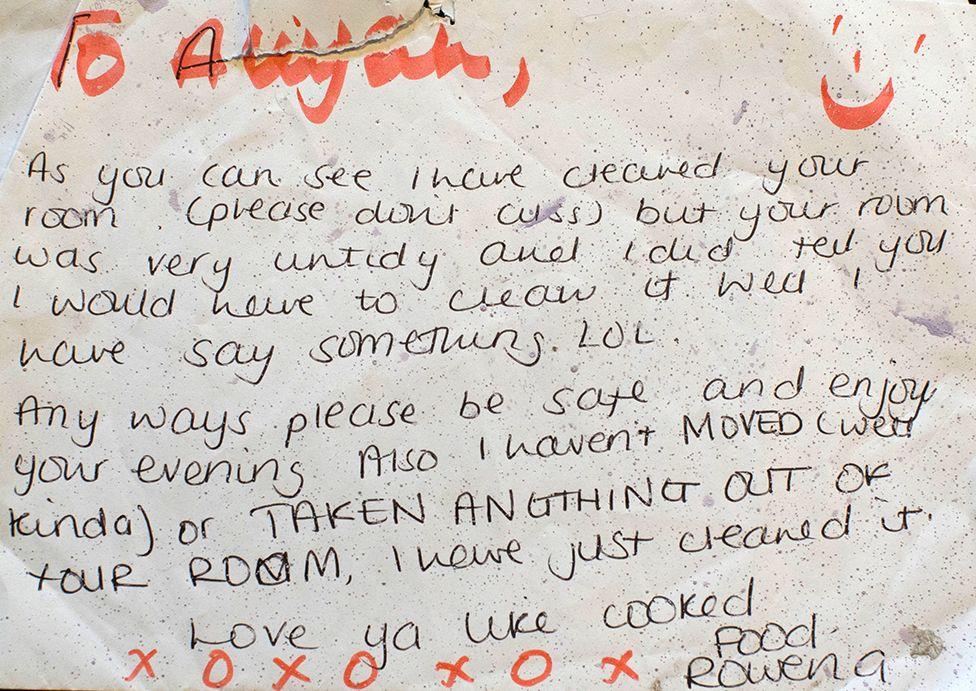

Note from Rowena to Aliyah

Rowena Miller was her assigned key worker - this was Rowena's very first job. Somehow Aliyah instantly knew that Rowena ultimately had her back. It was the first time in her life that she felt that someone believed in her.

"I was definitely traumatised from my life," she says. "And a bit of that still lives in me now.

"I know how to manage it a lot more than how I did before - because I didn't know I was traumatised. Before, I didn't know what was going on."

Watch: The moment Aliyah is reunited with her former care home mentor Rowena Miller

The effects of exploitation can last for years and many girls like Aliyah don't ever manage to escape it. But Aliyah did.

"That home toned me down," she says. "I wasn't lost any more."

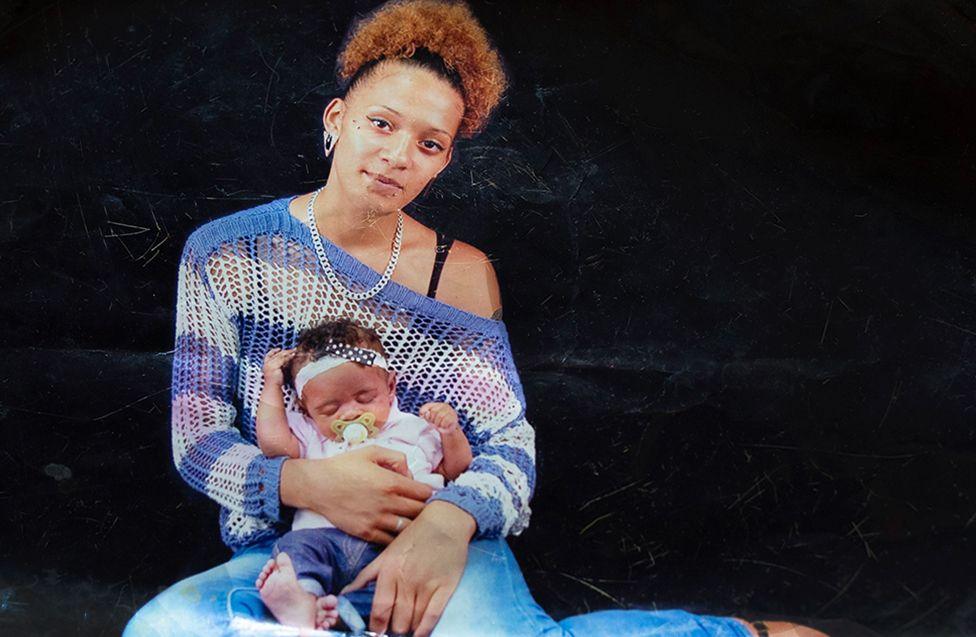

She left Bridges Lane with a new attitude. Then, aged 16, she discovered she was pregnant. It was a wake-up call. "I wasn't going to let my child experience even a quarter of what I went through," she says.

She knew she was still on the radar of social services and that her baby would be taken from her if she transgressed at all. She attended every single meeting she was called to, followed instructions to quit smoking and drinking.

Seven years ago, her daughter was born. It had been a hard pregnancy, but she believes the experience changed her life. "If it wasn't for her I wouldn't be here - she saved me," Aliyah says. "She's seven, and she experienced nothing I experienced when I was seven. And I thank the Lord every day for that."

Today Aliyah lives with her daughter in what she describes as not just a house, but also a home.

They live a normal life - Aliyah works, she enjoys writing poetry and is about to embark on studies to become a social worker so that she can help children in the same way that Rowena helped her.

"I'm still on a journey. My daughter is in my care. I'm a mum, I've got a home, not a house. I work. The community in the area that I live in, it smiles at me every day. I made it. And I'm in a better place."

You may also be interested in...

For many people, receiving a jail sentence would be the worst thing that ever happened to them. But when you've been experiencing domestic abuse - as most female prisoners have - you may see things slightly differently.