Sabotage and pistols - was Ellen Willmott gardening's ‘bad girl’?

- Published

She inspired the names of almost 200 plants, but the reputation of 19th Century horticulturalist Ellen Ann Willmott has been tarnished, with rumours that she sabotaged other people's gardens and carried a gun. In Chelsea Flower week, we look at a recent discovery which sheds new light on the gardening great - and her rude behaviour.

Miss Willmott's Ghost is a silvery, spiky sea holly that has a ghost-like appearance in gardens at dusk. Many gardening sites attribute its name to the infamous 19th Century horticulturist Ellen Ann Willmott. It was said Ellen would carry the seeds of this thorny plant in her handbag and scatter them surreptitiously in other people's gardens to sabotage their designs.

Rumour had it that Miss Willmott would carry around a loaded revolver in that handbag, too. But is this picture of a pistol-carrying guerrilla gardener accurate?

Ellen Ann Willmott was one of the leading gardeners, plant hunters and botanical photographers of her day. In 1897, she was awarded the Royal Horticultural Society's (RHS) most prestigious tribute, the Victoria Medal of Honour, a sign of how much her work was admired in an industry heavily populated by men.

Eryngium giganteum, otherwise known as Miss Willmott's Ghost

Of the 60 gold medals that were given out that year, only two were awarded to women - but Ellen never showed up to collect her award, sparking shock and disdain.

"The master of ceremonies kept having to say, 'Lady and gentlemen,' and he found this very embarrassing," says Sandra Lawrence, who has written a new book about the gardener.

Sandra, who has been fascinated with Ellen Ann Willmott ever since visiting her gardens as a child, says most people would just have assumed that Ellen couldn't be bothered to collect her medal and that it was typical of her.

"Nobody doubts that she was an incredible horticulturalist, a fascinating and very learned woman," says Sandra. But Ellen also had a reputation for not being very nice. "People have remembered her as being eccentric, grumpy, prickly. She gets accused of being both a miser and a spendthrift - and that she did unpleasant things."

But recently, Sandra discovered the likely reason for Ellen's no-show at one of the biggest events of her life wasn't rudeness, but the abrupt end to a love affair.

Ellen Ann Willmott grew up at Warley Place, a house and grounds in Brentwood, Essex. The family were comfortably middle class - but Ellen was a largely self-taught gardener, says Sandra, "because girls didn't get that kind of education". Still, under her influence the gardens at Warley Place became recognised internationally and were visited by the Royal Family. She cultivated stunning new species of daffodils and introduced a striking alpine rock garden, with cascading streams and a fern grotto.

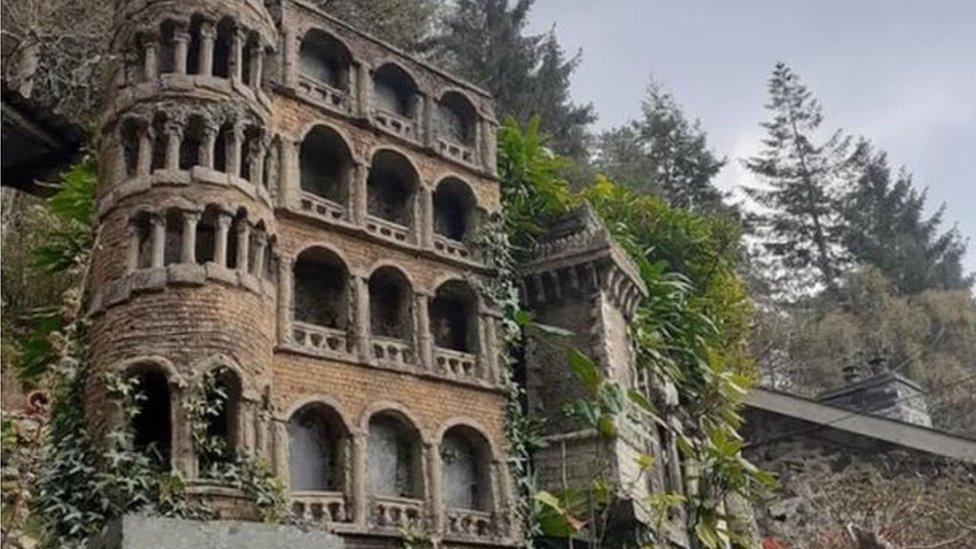

The house at Warley Place in Essex was demolished in 1939

As a child, Sandra used to explore the remnants of the alpine garden and hothouses once so loved by Ellen. "It was like my very own secret garden and I was sure there was treasure there," she says. Eventually she did discover riches - but not at Warley.

Following Ellen's death in 1934, her belongings were sent to Spetchley Park near Worcester, the home of her sister who married into the Berkeley family.

They languished there until 2019, when trunks filled with items were discovered rotting in a basement. With only days to clear it before builders arrived to start conservation work on the mansion, Sandra Lawrence and Karen Davidson, the Berkeley estate archivist, sifted through mouse skeletons, silverfish, dust, beetles and mould to uncover letters, documents, photographs, journals and receipts, transferring what they could salvage into bankers boxes.

They called it the "Willmott tombola", as they never knew what they would pull out.

"I put my hand in once and found a 1771 letter from the Empress Maria Theresa," Sandra says. They dug out the remains of a 100-year-old chocolate bar and the first eight pages of a lost Purcell sonata, as well as an autograph book for thumb prints, known as a "thumb-o-graph".

A trunk filled with Ellen Willmott's possessions

Sandra set about cross-checking her findings with other sources such as old newspapers, journals, diaries and train tickets. She even made an appointments diary for Ellen to recreate her movements.

Sandra discovered Ellen was a much more "nuanced individual" than the stereotype would have us believe - someone who pushed at the boundaries imposed on women.

Ellen made it her ambition to join learned societies where previously only men had been allowed. The Linnean Society, described as "the world's oldest active society devoted to natural history", were blackballing women and Ellen became one of the first to join.

"She was trying to get in with the big boys who'd had public school education, who had been to university, who read Latin, who could understand science and were already masters in their field," says Sandra. Despite this, she thinks Ellen lacked confidence. "I think she was dogged her whole life by thinking that she wasn't good enough and that somebody would find her out at some point."

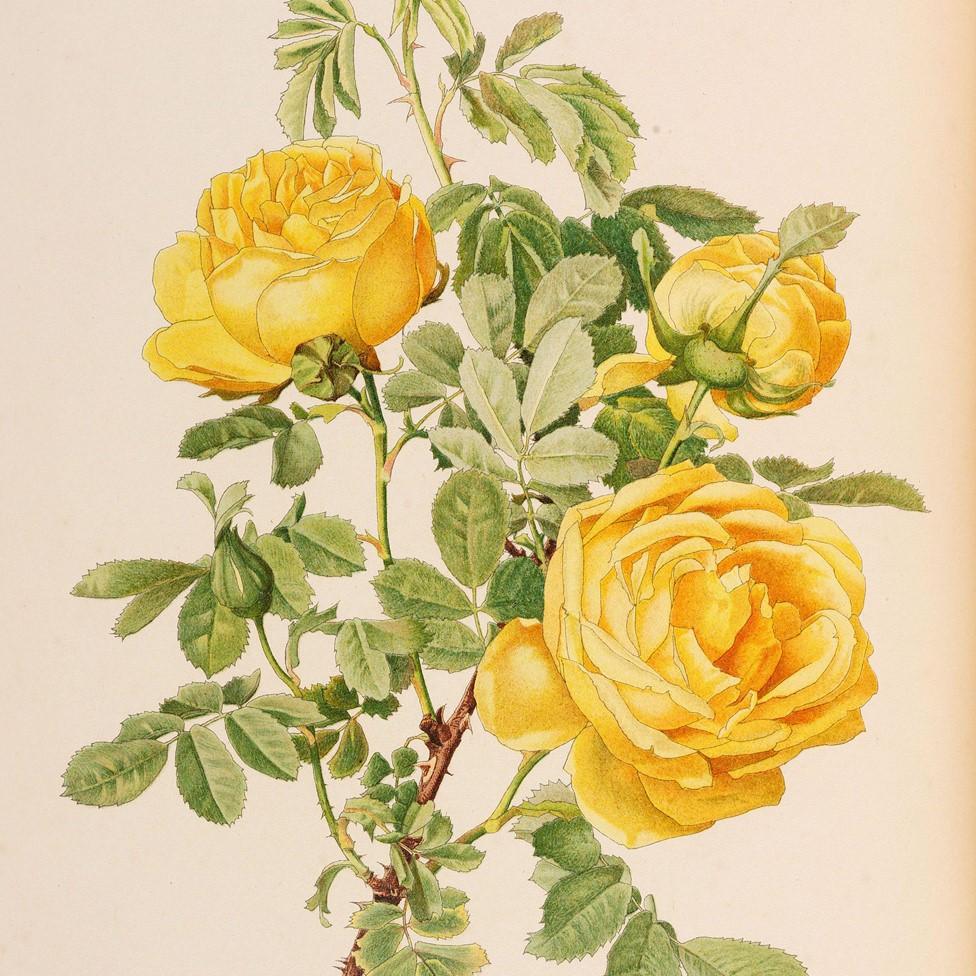

An illustration from Ellen Willmott's book The Genus Rosa

Sandra also thinks she knows why Ellen didn't show up to collect her prestigious RHS award.

Among the documents, Sandra and Karen found letters from a Miss Georgiana Tufnell, or "Gian". Gian had been one of Ellen's closest friends and worked as a lady-in-waiting to a member of the Royal Family, Princess Mary Adelaide. The letters from Gian suggest that she and Ellen had been deeply in love and were in a relationship together.

Gian first met Ellen in 1894 when she was 29 years old and Ellen was in her mid-thirties. Letters hint at the intimacy between the two. "You couldn't love me as much as you do and not know something of what I feel," Gian writes.

Sandra's research suggests that the women did not hide their affection. But after three years everything changed.

The health of Gian's employer, Princess Mary, had been deteriorating throughout 1897 and her death would have left Gian in a financially unstable position. Sandra describes how, on 13 October, to the shock of everyone, especially Ellen, an announcement was made about Gian's engagement to the very wealthy - and elderly - Lord George Mount Stephen, who was 35 years older than his future wife.

Lady Gian Mount Stephen

The wedding was scheduled to take place on 27 October, the day after the RHS ceremony in which Ellen was meant to receive her prestigious award. Sandra feels that if Ellen had been in London at the time, she would not have been able to avoid going to the wedding - and so she ran away to her property in France instead.

"I think she had a broken heart," says Sandra.

At the very last minute, however, the wedding had to be postponed until November, due to Princess Mary's sudden death following an emergency operation.

But what of Ellen's reputation as the malicious saboteur - secretly scattering the seeds of her namesake plant, Miss Willmott's Ghost?

"Of course it's a myth," says Sandra - and a fairly recent one at that. "It was only in 1980 [in a biography] that we first hear that story about her seed-bombing people's gardens - and it's a very handy one because it works as a really good metaphor for a prickly personality."

Besides, Sandra says she has never been able to get Miss Willmott's Ghost to take seed. "So it's not a very successful plant to seed bomb."

The story of how the plant became associated with Miss Willmott in the first place also remains somewhat of a mystery, says Sandra. "Back in 1966 a garden writer called Graham Stuart Thomas asked in a journal, 'Where did [the name of this plant] come from?' Nobody knew, and he got no replies."

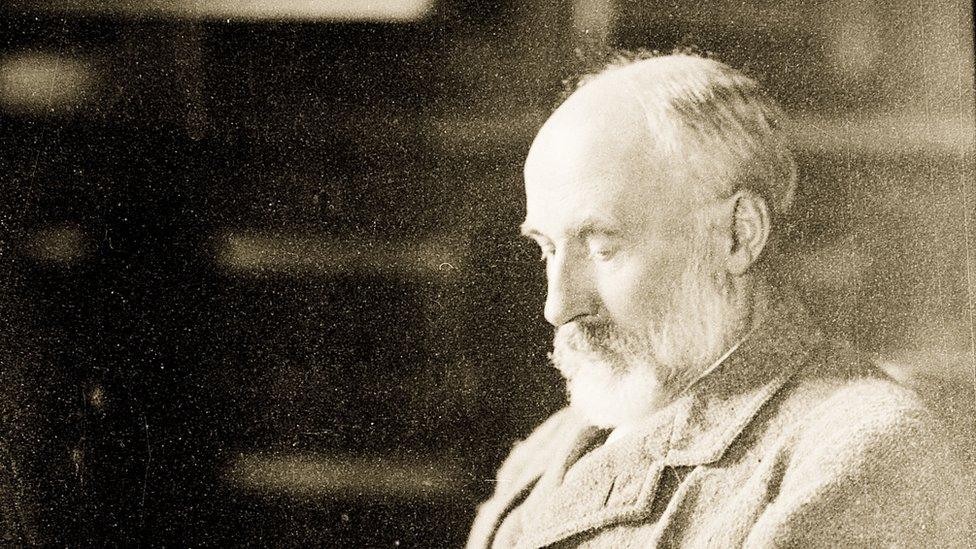

Ellen Ann Willmott

However, says Sandra, Ellen's pistol-wielding reputation is deserved.

"She carried a revolver in her handbag and I found a knuckle duster, but that's not necessarily for the reasons we might think."

When Sandra first found the knuckle duster among Ellen's possessions, she burst out laughing. "I had this idea of this 70-year-old woman who was spoiling for a fight, but I think she carried those things because she was scared."

In later life, at the end of the 1920s, Ellen had run out of money, "mainly because she spent it all", says Sandra.

Since she could no longer afford a car, Ellen had to travel by train and Sandra believes she carried the weapons for protection when walking to the station along a remote country lane.

A sea of daffodils at Warley Place Nature Reserve, near Brentwood in Essex

There are still more Willmott archives to process. In the end, Sandra hopes that Ellen - often omitted from the lists of gardening greats - will be judged more kindly and realistically.

"She was seminal in horticulture. I think her reputation now should be one of a human being that had huge amounts going for her." We should accept, says Sandra, "that none of us is perfect".

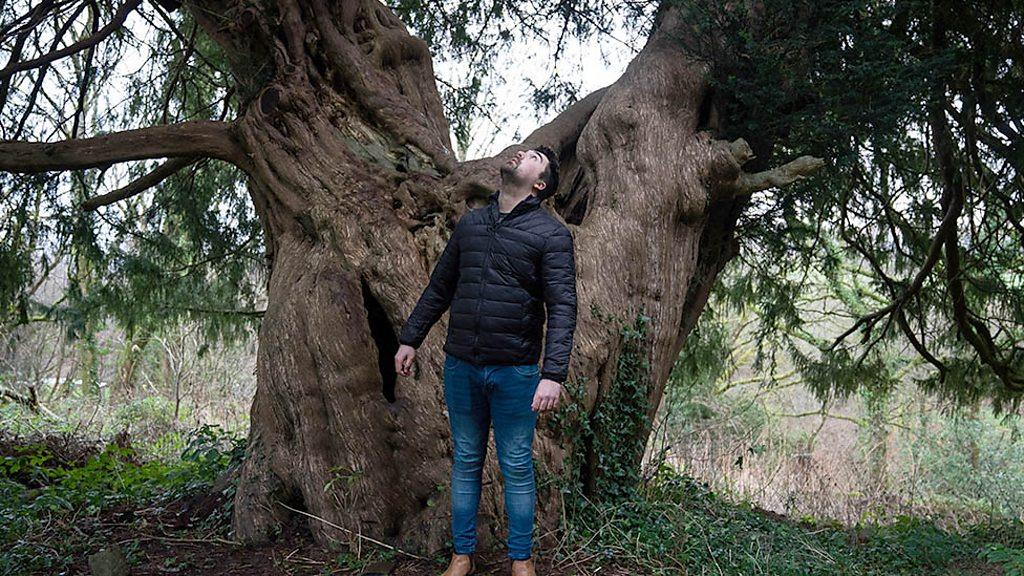

Warley Place is now a 25-acre nature reserve maintained by Essex Wildlife Trust. Yellow daffodils pop their heads up in spring and plants from across the world can still be found growing there - the real ghosts of Miss Willmott's legacy.

Sandra has written a book about her research entitled Miss Willmott's Ghosts.

Photographs of Ellen Ann Willmott and the house at Warley Place courtesy of the Berkeley family and the Spetchley Gardens Charitable Trust.

Related topics

- Published5 June 2021

- Published23 January 2022

- Published16 February 2021

- Published22 April 2022

- Published22 October 2021