Brains take over from video game controllers

- Published

Jonathan Fildes tries out the Emotiv Epoc

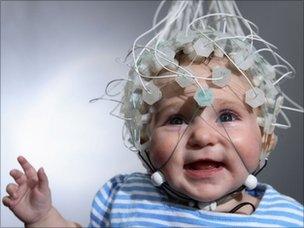

A wireless headset that can interpret brain waves to control video games and other onscreen action, had been shown off at a hi-tech conference.

The Emotiv Epoc claims to be the first neural headset aimed at consumers.

The system, which is already on sale, uses a century old medical technique to read electrical signals in the brain.

The technology then uses a series of algorithms to convert them into onscreen movement.

Home use

Although it can be used for gaming, the firm behind the technology believes that it has uses for interacting with computers and mobile phones, as well as controlling smart homes and even medical devices.

"Up until now the way we communicate with machines has been very limited," said Tan Le of Emotiv at the TED Global (Technology Entertainment and Design) conference in Oxford.

The headset uses non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG), a technique commonly used to diagnose and monitor epilepsy.

However, medical headsets cost thousands of pounds and specialist staff.

The Epoc headset is easier to set up than EEG systems used in medicine.

The Epoc headset, by comparison, costs less than $300 (£195) and can be used with a standard laptop.

It consists of 14 sensors that read the electrical signals from billions of nerve cells - or neurons - in the brain. These are transmitted wirelessly to the laptop.

"You train the system to recognise your specific way of thinking about something, then you can use that in any way you want," she said.

Teaching the device on a simple application takes a matter of minutes.

During a demonstration at TED, Ms Le showed someone making a cube on screen rotate and move using just their thoughts.

The headset was first released in 2009 and has so far largely been used by researchers, universities and companies interested in building applications, rather than gamers

Ms Le said that "tens of thousands" had been sold but it was far from being a mass-market device.

"For us, at this point the jury is still out whether this is a technology that will reach ubiquity - we know that," she told BBC News.

"We don't want to try to flood the market with a device that it is not ready for.

"Our focus is supporting the development and research community to bring out as many possible applications."

Processing power

Currently under development for the device are games - such as mind-controlled Tetris - and software to sort through photos.

Others are using it to build controllers for medical devices, such as prosthetics and wheel chairs.

Ms Le said there were also firms trying to merge the technology with other devices, such as mobile phones.

"Instead of thinking about pressing a series of buttons you would just think about calling a particular person," she said.

Many conference-goers tried the headset

Other firms were also using it to explore the possibilities of neural marketing, a technique used by advertising firms to see whether a potential buyer reacts favourably to ads.

"We take a direct biosignal from you that is very objective," she said.

The firm is currently working on refining the technology and allowing it to be used with other operating systems, such as Mac OS X and Linux.

Ms Le said Epoc had its sights set on refining the technology to make it capable of picking up and processing more subtle signals to make it more acceptable for everyday use.

"The greatest challenge we have right now is computational power - it is the challenge of optimising a set of algorithms that you can train on a normal PC within several minutes and have an immediate experience with the technology," she said.

"If we were going to build a brain technology that took months to train we could build in a lot more control."

However, over time, she said computers would inevitably become more powerful and more able to crunch more complex signals.

She said the firm was also thinking about introducing new elements such as kinetic charging, that would allow the device to be powered by a user's movements, rather than relying on a battery.

In addition, the firm hoped to shrink the technology for specific applications, such as mobile phones.

"We are only at the beginning of this journey," she said.

TED Global runs from 13-16 July in Oxford, UK.