Facebook data harvester speaks out

- Published

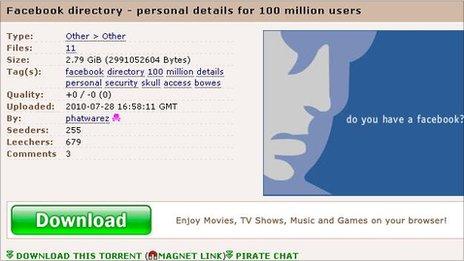

The torrent is attracting hundreds of downloads

The man who harvested and published the personal details of 100m Facebook users has spoken out about his motives.

Ron Bowes, a Canadian security consultant, used a piece of code to scan Facebook profiles, collecting data not hidden by users' privacy settings.

The list, which contains the URL of every searchable Facebook user's profile, name and unique ID, has been shared as a downloadable file.

Mr Bowes told BBC News that he did it as part of his work on a security tool.

"I'm a developer for the Nmap Security Scanner and one of our recent tools is called Ncrack," he said.

"It is designed to test password policies of organisations by using brute force attacks; in other words, guessing every username and password combination."

By downloading the data from Facebook, and compiling a user's first initial and surname, he was able to make a list of the most common probable usernames to use in the tool.

The three most common names, he found, were jsmith, ssmith and skhan.

In theory, researchers could then combine this list with a catalogue of the most commonly used passwords to test the security of sites. Similar techniques could be used by criminals for more nefarious means.

Mr Bowes said his original plan was to "collect a good list of human names that could be used for these tests".

"Once I had the data, though, I realised that it could be of interest to the community if I released it, so I did," he added.

Mr Bowes confirmed that all the data he harvested was already publicly available but acknowledged that if anyone now changed their privacy settings, their information would still be accessible.

"If 100,000 Facebook users decide that they no longer want to be in Facebook's directory, I would still have their name and URL but it would no longer, technically, be public," he said.

Mr Bowes said that collecting the data was in no way irresponsible and likened it to a telephone directory.

"All I've done is compile public information into a nice format for statistical analysis," he said

Simon Davies from the watchdog Privacy International told BBC News it was an "ethical attack" and that more personal information had not been included in the trawl.

"This is a reputational and business issue for Facebook, for now," he said

"They can continue to ride the risk and hope nothing cataclysmic occurs, but I would argue that Facebook has a special responsibility to go beyond doing the bare minimum," he added.

Snowball effect

Mr Bowes' file has spread rapidly across the net.

On the Pirate Bay, the world's biggest file-sharing website, the list was being distributed and downloaded by thousands of users.

Facebook hit its 500m user in mid June 2010

One user said that the list showed "why people need to read the privacy agreements and everything they click through".

In a statement to BBC News, Facebook confirmed that the information in the list was already freely available online.

"No private data is available or has been compromised," the statement added.

That view is shared by Mr Bowes, who added that harvesting this data highlighted the possible risks users put themselves in.

"I am of the belief that, if I can do something then there are about 1,000 bad guys that can do it too.

"For that reason, I believe in open disclosure of issues like this, especially when there's minimal potential for anybody to get hurt.

"Since this is already public information, I see very little harm in disclosing it."

Digital trends

However, he said, it also highlighted a new trend that was emerging in the digital age.

"With traditional paper media, it wasn't possible to compile 170 million records in a searchable format and distribute it, but now we can," he said.

"Having the name of one person means nothing, and having the name of a hundred people means nothing; it isn't statistically significant.

"But when you start scaling to 170 million, statistical data emerges that we have never seen in the past."

A spokesperson for Facebook said the list was "similar to the white pages of the phone book.

"This is the information available to enable people to find each other, which is the reason people join Facebook."

"If someone does not want to be found, we also offer a number of controls to enable people not to appear in search on Facebook, in search engines, or share any information with applications."

Earlier this year there was a storm of protest from users of the site over the complexity of Facebook's privacy settings. As a result, the site rolled out simplified privacy controls.

Facebook has a default setting for privacy that makes some user information publicly available. People have to make a conscious choice to opt-out of the defaults.

- Published29 July 2010

- Published26 May 2010

- Published21 July 2010