Campaign builds to construct Babbage Analytical Engine

- Published

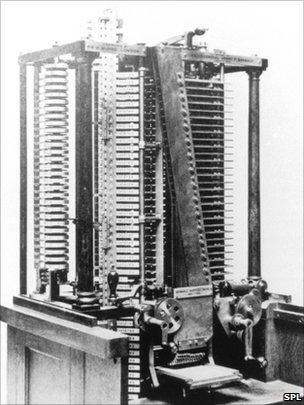

The Analytical Engine followed Babbage's work on the Difference Engine

A UK campaign to build a truck-sized, prototype computer first envisaged in 1837 is gathering steam.

More than 1,600 people have pledged money and support to build Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine.

Although elements of the engine have been built over the last 173 years, a complete working model of the steam-powered machine has never been made.

The campaign hopes to gather donations from 50,000 supporters to kick-start the project.

"It's an inspirational piece of equipment," said John Graham-Cumming, author of the Geek Atlas, who has championed the idea.

"A hundred years ago, before computers were available, [Babbage] had envisaged this machine."

Computer historian Dr Doron Swade said that rebuilding the machine could answer "profound historical questions".

"Could there have been an information age in Victorian times? That is a very interesting question," he told BBC News.

Number cruncher

The analytical engine was designed on paper by mathematician and engineer Charles Babbage. It was envisaged that it would be built out of brass and iron.

"What you realise when you read Babbage's papers is that this was the first real computer," said Mr Graham-Cumming. "It had expandable memory, a CPU, microcode, a printer, a plotter and was programmable with punch cards.

A complete Analytical Engine has never been built

"It was the size of a small lorry and powered by steam but it was recognisable as a computer."

Although other mechanical machines may predate the Analytical Engine, it is regarded as the first design for a "general purpose computer" that could be reprogrammed to carry out different tasks.

It was the successor to his Difference Engine, a huge brass number-cruncher.

"The Difference Engine is a calculator," said Dr Swade, who was part of a team that spent 17 years painstakingly building a replica. "It is not a computer in the general sense of the word."

He said that it would be "astounding" if the Anaytical Engine could also be built.

"The Difference Engine is already a legendary model, but it is dinky compared to the Analytical Engine," he said.

He said Babbage's many designs for the device suggested that it would be "bigger than a steam locomotive."

"That is with just 100 variables," he said. "He talked about machines with 1,000 variables, which would be an inconceivably large machine."

No one has built an entire Analytical engine, although various people, including Babbage's son and Dr Swade, have created elements of it.

Dr Swade said the most complex - although incomplete - recreations of elements of the machine have been built using Meccano by Briton Tim Robinson, external.

Confidence boost

Mr Graham-Cumming aims to recreate a design known as Plan 28 if his campaign is successful. However, he said, there would be a lot of work to do before then, including digitising Babbage's papers that are held at the Science Museum in London.

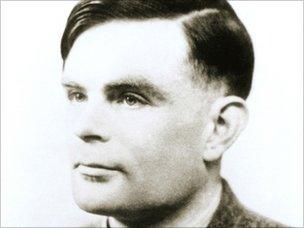

Mr Graham-Cumming previously led a successful campaign for a posthumous apology for Alan Turing

Dr Swade said that a researcher would also be needed to decipher Babbage's drawings and nomenclature.

"We would then need to build a 3D simulation of the engine [on a computer]," said Mr Graham-Cummings. "We can then debug it and it would make it available to everyone around the world."

Dr Swade, agreed that this was the correct approach and said a virtual recreation of the machine could solve "95% of problems" and allow them to use computer to design the thousands of individual parts needed to make the behemoth.

"Building a virtual engine is the only route of certainty to see the engine built in our lifetimes," he said.

When he built the Difference Engine, this route was not available he said.

First, however, Mr Graham-Cumming needs to raise the money to set up the non-profit Plan 28 organisation to oversee the work, external.

"I was a little worried whether enough people would care about a steam-powered computer, with 1k of memory that was 13,000 times slower than a [Sinclair] ZX81," he said.

However, he told BBC News, an earlier online campaign had helped persuade him that it was possible.

Last year he launched a petition on the No 10 website calling on the government to make a posthumous apology to World War II code-breaker and computer pioneer Alan Turing for his treatment by the authorities for being gay.

In August 2009, then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown wrote a letter in the Daily Telegraph saying that he was sorry for what had happened, external.

"That gave me the confidence that there are enough people that care about computing to get this kind of thing done," he said.