It's digital, but is it art?

- Published

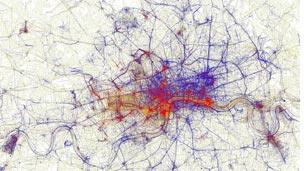

Maps plotting where tourists and locals take pictures in London creates unusual images

Bill Thompson likes the ways technology and art intersect.

At a recent conference on the future of the arts in a digital world the opening night panel was asked to name a digital art work that had impressed them.

All stumbled, perhaps unsure of who was doing 'interesting' work in this rapidly changing field, leaving the delegates at the Media Festival/Arts with the sense that digital might not really count as far as they were concerned.

My first thought was that the most interesting piece of digital art I'd come across in the last year was definitely the new album from The Editors.

In This Light and on This Evening is a wonderful work, and everything about it apart from the vibration of Tom Smith's vocal chords and the strings of Chris Urbanowicz's guitar is the product of digital technologies, first in the studio and as then it is distributed and played.

It surely has the right to be called a digital art work, even if it is then embedded in a commercial model that is struggling to adapt to the realities of the network economy.

One musician whose work is definitely - and sometimes defiantly - digital is cellist Peter Gregson.

On Monday evening I sat enthralled as he performed in King's Place London in a recital that combined his own compositions with works from Steve Reich and Max Richter, accompanied on screen by technology provided by Microsoft Research and others.

We enjoyed a World Wide Telescope fly-over of Iceland, the time-lapse photographs from a SenseCam worn by his collaborator, Microsoft's Tim Regan, as he delivered material to the venue and some of the astonishing maps Eric Fischer makes by plotting the location data from Flickr photographs of major cities, along with some astonishing data visualisations., external

I love Peter's work, but can't escape the realisation that I had been online for nearly five years before he was born.

He has grown up into a world infused with the potential of digital technologies, and it is clearly evident in his astonishingly confident and compelling performances in which he alternates between two cellos, a Colin Irving acoustic cello familiar from any string quartet, and a custom five string Erik Jensen electric cello, a strange skeletal beast that plugs directly into his digital toolbox to provide a transformed sound that he harnesses into music.

Later in the week I spent a fascinating hour in the company of Matthew Applegate, better known as Pixelh8, as he explored the realm of chip tunes - music made from old computers - in a talk at Kettle's Yard gallery in Cambridge, part of their celebration of the work of John Cage.

Hybrid world

Digital music is transforming how tracks are shared at parties

Matthew described his experience working with the old computers at the National Museum of Computing in Bletchley Park, and the joy of composing electronic music to the rhythm provided by hand-cranking an old mechanical calculator.

Both Peter Gregson and Matthew Applegate work in ways that simply do not recognise the boundary between digital and analogue, and they belie any claim that we now live in a 'digital' world.

Matthew's use of a soldering iron, and Peter's technical expertise with his instrument, remain profoundly located in the physical world, even if they incorporate digital technologies into their creative processes.

What they show is that we now live in a hybrid world.

I faced up to this hybrid world myself recently when I celebrated my fiftieth birthday and had to decide what music to play.

In the old days we'd have had a stack of 45rpm singles and invited people to choose what to play next, but my old singles are in a cupboard, untouched for years.

I toyed with the idea of making a playlist or two, but that would have meant planning in advance and also assumed that I could anticipate the way the tone of the party would change over time.

Shiny toy

This is tricky - I'm always ready to segue into The Clash's first album, but maturity has taught me that others can feel differently.

So I decided to follow the modern fashion in government and return control to the people, empowering the party-goers to find their own solutions to the problem of what to listen and dance to.

I plugged the loudest speakers I could find into my desktop computer and started iTunes, and used the Remote app on my iPad to select the songs.

Over the evening the iPad was passed around and anyone who wanted to could choose what we listened to.

Apart from a few rather painful transitions when people started their song playing too early it worked really well, and anyone who wasn't sure what to put on next could simply use the 'Genius' button to select similar songs to the one currently playing.

Using the iPad as control pad was fascinating, as a touchscreen device offers a far more intuitive and enjoyable way of engaging with what is on offer than any remote control ever could, with dozens of tiny buttons and obscure icons.

Remote on the iPad is exactly the same as using iTunes on the desktop, and even though it's a poorly designed piece of software it did the job remarkably well.

Of course my creative use of digital technology only involved connecting the pieces together and taking the risk that my expensive shiny toy would end up broken or soaked in prosecco, while Peter Gregson and Matthew Applegate are both exploring the artistic and performative potential that the new tools offer.

But I like to think that we are all moving in the same direction, and that we'll soon reach the stage where it makes as little sense to talk about 'digital art' as it does about 'new media'.

Bill Thompson is an independent journalist and regular commentator on the BBC World Service programme Digital Planet. He is currently working with the BBC on its archive project.