Is Kenya sabotaging its broadband future?

- Published

In 2009, the first undersea cable to bring high-speed internet access to East Africa went live. The BBC has returned to the region 18 months on to find out what has changed as a result.

"The internet is probably more important than water," says Dr Bitange Ndemo.

He is joking, but the laugh is forced.

The softly spoken permanent secretary of Kenya's Ministry of Information and Communications is preparing for a showdown.

In the previous week, a growing number of fibre optic cables that run around Nairobi and into the more affluent areas have been dug up in the middle of the night and cut, causing communication blackouts.

Dr Ndemo believes it is sabotage.

"It is not foolish people doing this," he says. "When they make a cut, they cut through the primary cable and the [back-up] cables."

The attacks have been blamed by many on digital turf wars between rival firms, keen to grab any advantage in the emerging broadband market. Others blame disgruntled employees.

But whoever is responsible, the government has made it clear they will not tolerate anyone jeopardising the country's digital future.

Dr Ndemo says he would like to see life sentences doled out to anyone found cutting cables.

In the meantime, the government has deployed security teams to protect key parts of the fibre networks and set agents to work investigating the cuts.

Eighteen months after the arrival of the first of three undersea internet cables to connect Kenya to the rest of the world, the government is not taking any risks.

Huge anticipation

Sabotage is just one of the teething difficulties of Kenya - and East Africa's - digital emergence.

But it should not overshadow the region's achievements or pace of development.

The race is on to wire up Nairobi and beyond

The country proudly boasts three separate cables - Seacom, Teams and Eassy - that connect it to the rest of the world.

More than 20,000km of fibre stretches inland and surrounds major conurbations, 3G mobile towers cover cities like Nairobi and long-range wireless masts using Wimax technology have appeared.

"We are moving at high speed," says Dr Ndemo, who was one of the most vocal supporters of the campaign to wire up the region.

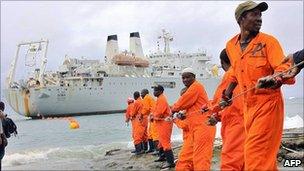

When the first cable landed, Brian Herlihy, the CEO of Seacom said its arrival marked "the dawn of a new era for communications".

"Turning the switch 'on' creates a huge anticipation but ultimately, Seacom will be judged on the changes that take place on the continent over the coming year," he said.

Since then, the increased bandwidth has given a boost to mobile services, the burgeoning tech scene of home-grown developers, programmers and designers, whilst it has also attracted big business.

"It would be disingenuous to say that they couldn't do business here [before the cables arrived]," said Paul Kukubo, head of Kenya's ICT board, which is responsible for promoting technology in the country and abroad.

"But it has given them the confidence to site their operations here."

It has also boosted the number of people online; the Communications Commission of Kenya estimates that the number of internet subscriptions in the country have jumped from 1.8m to 3.1m in the twelve months after the cables arrived.

But tellingly, almost all of the growth has been in the slower, cheaper mobile internet. This is, in part, because Kenya is almost saturated with mobiles.

But there are other reasons why for the vast majority of people in the country, high-speed broadband is still a pipedream.

"The government were saying it was going to be so cheap when the cable arrived," says Chris, a taxi driver in Nairobi.

"We thought it was going to be for everyone but instead it is still just for the privileged few."

Money demands

For some, this situation is difficult to reconcile, particularly when wholesale bandwidth costs dropped by 90% when the cables arrived.

Julius Opio of Seacom said that before the first cable was connected, bandwidth could cost $2,400 per megabit through a satellite. Now, he says it is a "few hundred dollars".

The situation has led to accusations of profiteering, collusion and price-fixing, something the ISPs deny.

They accept that the costs have dropped but they say the equation is not as simple as it may appear.

"Bandwidth is just one of seventeen costs," said Kris Senanu, managing director of the internet division of ISP Access Kenya, one of the country's largest providers. "The other sixteen haven't changed."

He says that the firm has also had to pay out to lay the fibre networks around the city and in some cases to wire up buildings.

"Landlords of buildings want payment to put fibre into their buildings," said Mr Senanu. "They say: 'I know it will make you a lot of money and I want my share'."

On average, he pays 5,000 Kenyan shillings (£40) every month to landlords who demand payment.

As a result, broadband prices have remained high, although speeds have increased.

Packages do exist that cost 999 Kenyan shillings (£8) per month, but they offer just 128Kbps on a shared line that is only usable at off-peak hours. A connection with speeds of 1Mbps cost around four times that price.

'Dirty tricks'

But there are other reasons why costs have remained high.

ISPs such as Access Kenya own their own networks - so far, the company has laid 140km of its own fibre in Nairobi.

Eighteen months from when the cable was brought ashore is still not available to all

"We can't rely on others," said Mr Senanu. "In this market, if you don't own it all from tip to toe you can't provide reliability."

This lack of trust has led other ISPs to do the same.

And in the race to recoup the high costs of laying this fibre, ISPs all target the most affluent areas of Nairobi.

As a result, some areas can have three or four fibre optic cables - all from different providers - running alongside each other.

For Dr Ndemo, this is one of the main hurdles to rolling out broadband more widely.

"They will never reduce costs when they are using infrastructure as a competitive edge," he says.

Some speculate that this situation is the root cause of the fibre optic cuts - as networks try to gain a competitive edge on their rivals in the most lucrative markets.

But as well as encouraging dirty tricks and keeping costs high, it also means that broadband is the preserve of elite digital ghettos.

"Those that actually need the internet are the very poor people," says Dr Ndemo.

He says that the ISPs are missing a trick by not rolling out their services to less affluent regions.

Steady pace

Now, he believes the government must step in.

"The only way [the price] can come down is if infrastructure becomes an open access platform just like the road network," he says.

He is now considering - along with the regulator finding "acceptable mechanisms to force these operators to share infrastructure", he says.

This already happens successfully in many countries - such as the UK.

In addition, he says, the government is already working on "last mile solutions" to bring the internet to those areas that may not be served by the market.

He is talking to local authorities to find ways to roll out fibre-to-the-home technology in less well off urban regions and also has a plan to roll out next generation mobile networks, using so-called high-speed Long Term Evolution (LTE) technology, to connect rural areas.

"Once we are done [the internet] will be affordable for everyone," he says.

Come back in 12 months time and the changes - and cheap broadband - will be there for all to see and experience, he says.

Critics point out that the government had similar soundbites when the first cables arrived. They are also sceptical about the government's ability - and budget - to do this.

But Dr Ndemo shrugs this off.

"Everybody laughed when we said we would bring fibre to Kenya," he says. "Nobody believed we would have a first world infrastructure."

He says he is happy with the pace the country is now moving.

"These things don't happen overnight - give us time."