Wikileaks' struggle to stay online

- Published

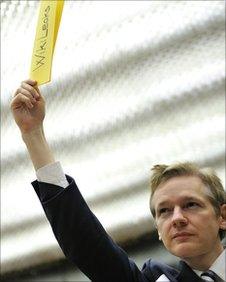

Julian Assange has now been arrested

For rolling news outlets Wikileaks has been a dream come true with thousands of US embassy cables dribbling out titbits of sensitive information and providing new headlines on a daily and even hourly basis.

But for the US government, the revelations are less welcome.

The site has become its bete noire and after making its displeasure clear, US firms that have dealings with it have been quick to turn their backs.

The troubles began for Wikileaks when Amazon which hosted its servers in the US, withdrew services saying the site was breaking its terms and conditions.

They continued when EveryDNS, the domain name firm which allowed the Wikileaks.org address to be translated into an IP address, withdrew services.

Without it, the .org site was effectively shut down.

EveryDNS said that it had terminated services because web attacks aimed at Wikileaks "threatened the stability of the EveryDNS.net infrastructure which enabled access to almost 500,000 other websites".

But despite losing many links in its supply chain, Wikileaks remains defiantly online.

So how has it avoided the noose that the US government seems determined to make for it?

"It has moved stuff to Europe where things are out of the reach of the US government," said Paul Mutton, a security expert at internet research company Netcraft.

It has created additional IP addresses, the raw information internet routers use to find content.

And it now has some 14 DNS servers which do the same job that everyDNS refused to do.

"It will be harder to take Wikileaks down because they are using so many domain name servers. Anyone wanted to shut them down would have to target companies in 14 different countries," said Mr Mutton.

Within hours of having its .org address cut off, Wikileaks moved to a Swiss address .ch, which pointed to an IP address in Sweden with servers located in France.

Wikileaks has effectively weaved itself a complex web of suppliers and it seems even the domain name companies are confused.

One of its providers, easyDNS, issued the following statement.

"There is some confusion around control over the wikileaks.org domain and who has it. To be honest, it turns out we are not dealing with actual Wikileaks people on the backend, but third-parties who are co-ordinating a DNS effort for them, including the initial fallback domain, wikileaks.ch," it said.

The company has been savvy enough to do dealings with firms which are likely to be sympathetic to its cause.

So in Sweden, for example, its web hosting firm is PRQ which describes itself as committed to free speech.

"If it is legal in Sweden, we will host it, and will keep it up regardless of any pressure to take it down," it said on its website.

In France, Wikileaks is hosted by provider OVH and in recent legal wrangles the web provider revealed that it only realised it was doing business with the whistle-blowing site after reading press reports.

It also revealed how easy it is to get a web service up and running.

"Wikileaks ordered a dedicated server with protection from cyber attacks through OVH's website using a credit card to pay the 'less than 150 euro bill'," managing director Octave Klaba said.

Web attacks

As well as having the official net channels it needs to function online closed down, Wikileaks has also been the victim of so-called distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

Such attacks bombard the site with requests for information making the site hard to access.

Some have speculated that the US government could be behind the attacks.

It would be very difficult to find out where they emanated from, said Ian Brown, of the Oxford Internet Institute.

"Unfortunately it can be virtually impossible to identify the actual source of a DDoS attack because the attack itself is mounted by tens or hundreds of thousands of computers.

These "bots" are ordinary computers that have been commandeered without their owner's knowledge or consent, often through a computer virus," he said.

Mikael Vibrog, head of Wikileak's Swedish service provider PRQ, said that such attacks are not uncommon.

"We have been suffering DDoS attacks for years, not just against Wikileaks but against our other customers too," he said.

But while they may be an effective way to take a site down they are unlikely to emanate from national governments, thinks Mr Mutton.

"Most governments would stick to legal methods for dealing with websites," he says.

So if a government was hell-bent on stopping Wikileaks, could it simply block access?

In France it seems the attempt is not running that smoothly.

French industry minister Eric Besson called for Wikileaks to be banned from French servers after the site took refuge there last week.

But a court in Lille has declined to force web provider OVH to shut down the site.

The site itself is only part of the problem for those determined to silence Wikileaks.

One of its biggest allies in the wake of it losing its .org address was micro-blogging site Twitter.

Wikileak's Twitter page responded immediately by publishing the site's IP address and alerting people to the mirror sites that popped up quickly after .org went down.

To date, there are over 500 of these mirror sites.

The site it seems is literally getting bigger by the day.

Even the arrest of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange in London on Tuesday will have no impact on services.

Secret file

"Wikileaks is operational. We are continuing on the same track as before," said Wikileaks spokesman Kristinn Hrafnsson.

It will be run by a group of people from London and other locations, he said.

But perhaps most importantly the information at the heart of the controversy is also already in the hands of downloaders.

"Wikileaks has released an encrypted file containing all of the embassy cables," said Dr Joss Wright, a research fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute. "The information is already out there."

Thousands of copies of that encrypted file have been shared using peer-to-peer networks, like BitTorrent. "Once the information is there, it's virtually impossible to stop people sharing it," he added.

One of the biggest lessons that can be learnt from the Wikileaks affair is that in an internet-age where information can be disseminated virtually in the flick of an eye, secret information needs to be better protected.

Jonathan Zittrain, professor of law at Harvard Business School and co-founder of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, predicts there will be a sea-change in how governments handle information.

"They may have to rethink how they treat secret material," he said.

- Published3 December 2010

- Published7 December 2010

- Published9 December 2010

- Published8 December 2010