Tech Know: Minty geeks and flirty beermats at the Maker Faire

- Published

Flirting beer mats, truth bracelets and robot bouncers: Ellie Gibson takes a tour of the Newcastle Maker Faire

There's no doubt that the net has helped those who enjoy tinkering with technology to find fellow enthusiasts to share their ideas with.

In warehouses and workspaces all over the country, face-to-face meetings of makers and hackers are taking place ever more often. However, there's only one national event that brings lots of them together all at once.

That place is the annual Maker Faire in Newcastle. This year the gathering was bigger than ever. There were more exhibitions to tempt the curious and the geeky. Everything from mushrooms that make music to steampunk jewellery.

Even the weather was on the side of those attending. The forecast rain never materialised, which was just as well as the Faire was so popular that some had to queue for almost an hour to get in on the opening morning.

Visitors to the Maker Faire were greeted by inventor Paka's fire breathing dragon

This being the Maker Faire, attendees did not simply have to stand and wait. There were entertainments and exhibitions in the square outside the Centre for Life museum.

Inventor Paka showed off his 8m-long fire-breathing dragon made of scrap. Bo the Clown cycled around on his connected bike and there was also the biology-inspired Bulge sculpture made of stretch cotton by Bethan Maddocks for folks to see, squeeze and squish.

Parked in the square was Tom Ward's Tech Truck, a panel van that had been converted into a mobile hacker space.

Those taking a turn inside could build a nippy little robot controlled via a TV remote.

Mr Ward plans to use the Tech Truck as he travels round the country running tech bootcamps at schools and other events.

"We'll be teaching kids soldering and practical skills that they probably won't learn at school," he said.

The focus on curriculum and exams has left little time to tinker and create, said Mr Ward.

"The kids get so much more interested when they can actually build something," he added.

Handy robots

Minty Geek packs easy to do electronics projects into a handy tin

Also aiding the efforts of the novices was Minty Geek, an initiative whose name builds on one of the unsung heroes of the hacking world - the mint tin.

These tins, once all the sweets have been eaten, have found a role in hundreds of hacker projects.

Thought up by Dr Mark Brickley, the idea behind Minty Geek is to produce a project every month that allows people to learn more about electronics.

The parts of each project, of course, come in a mint tin and some even use the confectionery container as a key part of the finished gadget. Projects that can be completed in the first kit include a cookie jar alarm, lie detector and egg timer.

Elsewhere at the faire, a team from Newcastle University was showing off an electronic bar that can read the position of beermats placed on top of it.

Projectors mounted underneath are used to display messages, passing from one mat to another.

Its inventors claim the technology could be used to help shy drinkers who can't quite manage human flirting.

Also fooling around with electronics was MBed Robots, an offshoot of UK chip designer Arm which is providing kits to build simple robotic systems.

As well as these new entrants, the Maker Faire featured lots of established organisations such as Element 14, Instructables, RoboSavvy, HACman and NortHACKton.

Moving parts

Jim MacArthur brought along not one, but two, mechanical computers.

But not all of the Maker Faire was about helping the novice, indeed part of its charm is its ability to turn up the utterly unexpected.

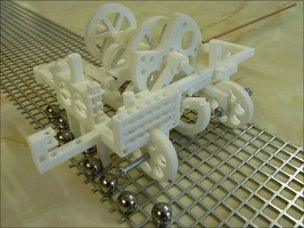

The machine, built by Jim MacArthur, certainly fits that bill. He has created a mechanical computer that is programmed by the movement of ball bearings.

Students of computer history will recognise it as a Turing machine, just like the one Alan Turing thought up and explored in the mathematical paper that kicked off the computer age.

All the processing in the mechanical computer is carried out via a chunk of wood with specially shaped holes in it that holds the balls, or "data".

It does have a power source but all that does is keep it moving along the track following the trail of ball bearings. Magnets and gravity do the number crunching.

"It's programmed by a sequence of ball bearings and its output is a sequence of ball bearings," said Mr MacArthur.

He added that his back-of-an-envelope calculation suggested that it would take a month of continuous operation to complete a sum like 1+1.

"Because it is a really simple Turing machine, it's really inefficient," he said.

He explains that the Turing machine took about a year to put together. But then, time matters little to the makers, whose sole motivation is a love of the craft.

- Published1 March 2011

- Published3 February 2011