Are secure websites still safe?

- Published

SSL is supposed to keep user data secure, but recent hacks have raised questions about its value

Ask anyone to recall a three-letter acronym associated with the web and they will probably trot out LOL, OMG, WWW and perhaps even WTF.

But quiz them on what SSL stands for and you are likely to get blank looks.

Yet those three letters and the technology they refer to are more integral to the web than almost all of the other acronyms.

SSL stands for Secure Sockets Layer and, along with the associated TLS system, it is the method by which traffic between a website and anyone visiting it is encrypted to prevent eavesdropping.

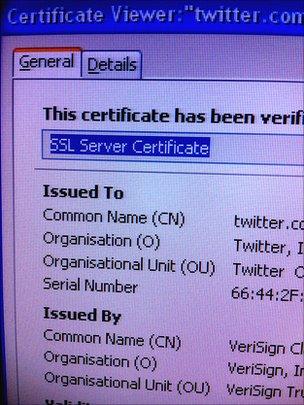

When connecting to a secured site, a user's web browser is able to automatically verify its authenticity.

It does this by requesting a digital certificate which is checked against a list held by a third-party "certificate authority".

Most people encounter the system when they visit an online shop and use a credit or debit card to make a purchase. SSL protects those card numbers and other identifying details as they fly across the web.

Increasingly e-mail and social networking sites are using secure connections to safeguard communications between themselves and their users.

Both Twitter and Facebook have recently introduced SSL encrypted options.

The technology is ubiquitous, embedded in the web and some believe, thanks to recent attacks on it, badly broken.

Several social networks, including Twitter, now use secure connections

Warning words

In March 2010, security researchers Christopher Soghoian and Sid Stamm published a paper, external which warned that the SSL mechanism was vulnerable to a variety of sophisticated attacks.

Sure enough, in March 2011, just such an attack was carried out against Comodo - one of the firms that helps to operate and administer the SSL system.

"This is one of those cases where I can say I told you so but it doesn't feel good to be able to say that," said Mr Soghoian.

The attack allowed a hacker to impersonate a series of high profile websites including Google, Yahoo and the site that hosts add-ons for the Firefox browser.

Paul Mutton, a security analyst at monitoring firm Netcraft, which gathers data about SSL, said the person responsible was probably trying to set up a situation where they sat between users and the sites that they wanted to visit.

That malicious middleman would have been able to scoop up data, read it, and then pass it on to the legitimate site.

"The attacker would be acting as a proxy and be able to see your user name and password," said Mr Mutton.

Given that the Comodo attack originated in Iran, some observers have speculated that it was part of an attempt by the Iranian government to find out more about protesters organising via web-based services.

Mr Mutton said that questions about the hacker's identity had only partially been answered when they posted to the Pastebin website, external details of the information used to perpetrate the attack.

"There's still speculation as to whether the hacker is an individual as he claims or not," he said.

The attack was only detected, according to Mr Mutton, because such high profile sites were chosen to be impersonated. Using sites with far less traffic might have gone unnoticed.

"It does make me wonder if this has happened in the past and no-one knows about it," he added.

Stuxnet attack

SSL certificates also played a key role in the Stuxnet attacks. The worm, which was designed to hijack industrial control systems, is believed to have been created to disrupt Iran's nuclear programme.

Stuxnet's creators are likely, according to the analysis produced by security firm Symantec,, external to have needed to get hold of SSL certificates in order to create files that had been "digitally signed to avoid suspicion".

Symantec surmises that to obtain digital certificates, someone may have physically entered the premises of the firms which issue such certificates and stolen them.

Papers please

Breaches such as Comodo and Stuxnet have sparked concerns that the SSL/TLS system is not as secure as previously thought and may be giving users false confidence.

Only a handful of certificate authorities are supposed to issue the guarantees of identity. In practice there are thousands of them.

The exact number has never been disclosed, explained Christopher Soghoian, and there is little scrutiny of how they operate.

What these episodes should trigger, he suggested, is a reduction in the number of CAs and greater oversight of who their partners are and how trust is transferred.

"As 90% of the certificates on the web are issued by 24 CAs, I hope we will now have some momentum to reduce their numbers," he said.

"There's a growing awareness that they are not serving the public interest."

- Published24 March 2011

- Published25 March 2011

- Published29 March 2011

- Published10 February 2011