The man who invented the microprocessor

- Published

40 years after Intel patented the first microprocessor, BBC News talks to one of the key employees who made that world changing innovation happen.

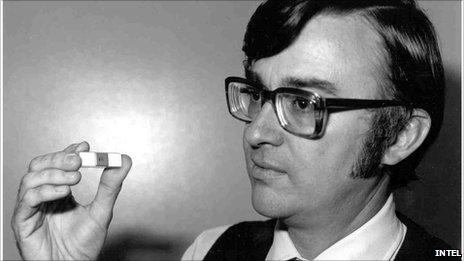

Ted Hoff saved his own life, sort of.

Deep inside this 73-year-old lies a microprocessor - a tiny computer that controls his pacemaker and, in turn, his heart.

Microprocessors were invented by - Ted Hoff, along with a handful of visionary colleagues working at a young Silicon Valley start-up called Intel.

This curious quirk of fate is not lost on Ted.

"It's a nice feeling," he says.

Memory

In 1967 Marcian Edward Hoff decided to walk away from academia, having gained his PhD in electrical engineering.

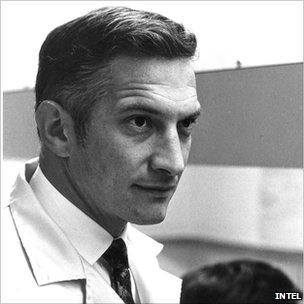

Robert Noyce, the "Mayor of Silicon Valley", head-hunted Ted Hoff for his new company

A summer job developing railway signalling systems had given him a taste for working in the real world.

Then came a phone call that would change his life.

"I had met the fella once before. His name was Bob Noyce. He told me he was staffing a company and asked if I would consider a position there," says Ted.

Six years earlier, Robert Noyce, the founder of Fairchild Semiconductor, had patented the silicon chip.

Now his ambitions had moved on and he was bringing together a team to help realise them.

"I interviewed at Bob Noyce's home and he did not tell me what the new company was about," says Ted.

"But he asked me if I had an idea what the next level for integrated circuits would be and I said, 'Memory' ".

He had guessed correctly. Mr Noyce's plan was to make memory chips for large mainframe computers.

Ted was recruited and became Intel employee number 12.

In 1969, the company was approached by Busicom, a Japanese electronics maker, shopping around for new chips.

It wanted something to power a new range of calculators and asked for a set-up that used 12 separate integrated circuits.

Ted believed he could improve on that by squashing most of their functions onto a single central processing unit.

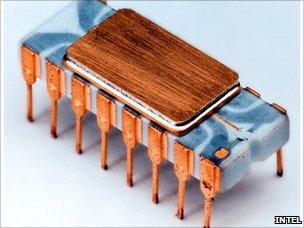

The result was a four-chip system, based around the Intel 4004 microprocessor.

Sceptics

The four-bit 4004 microprocessor was originally designed for a Busicom calculator

Intel's work was met with some initial scepticism, says Ted.

Conventional thinking favoured the use of many simple integrated circuits on separate chips. These could be mass produced and arranged in different configurations by computer-makers.

The entire system offered economies of scale.

But microprocessors were seen as highly specialised - designed at great expense only to be used by a few manufacturers in a handful of machines.

Time would prove the sceptics to be 100% wrong.

Intel also faced another problem.

Even if mass production made microprocessors cheaper than their multiple-chip rivals, they were still were not as powerful.

Perhaps early computer buyers would have compromised on performance to save money, but it was not the processors that were costing them.

"Memory was still expensive," says Ted.

"One page of typewritten text may be 3,000 characters. That was like $300 [£182].

"If you are going put a few thousand dollars worth of memory [in a computer], wouldn't it make more sense to spend $500 for a processor built out of small- or medium- scale electronics and have 100 times the performance.

"At that time, it didn't really make sense to talk about personal computers," he said.

Over time, the price of computer memory would began to fall and storage capacity increase.

Intel's products started to look more and more attractive, although it would take another three years and four chip generations before one of their processors made it into a commercially available PC.

Moore's law

Intel knew its system would win out eventually.

It could even predict when microprocessors would make the price-performance breakthrough.

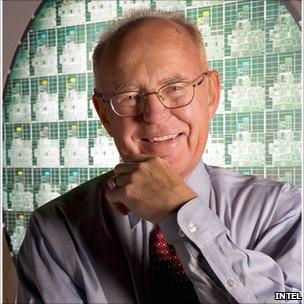

In 1965, Gordon Moore, who would later co-found Intel with Robert Noyce, made a bold prediction.

Gordon Moore's law continues to hold, almost half a century after he proposed it

He said: "The complexity for minimum component costs has increased at a rate of roughly a factor of two per year".

The theory, which would eventually come to be known as Moore's Law, was later revised and refined.

Today it states, broadly, that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit will double roughly every two years.

However, even Mr Moore did not believe that it was set in stone forever.

"Gordon always presented it as an observation more than a law," says Ted.

Even in the early days, he says, Intel's progress was out-performing Moore's law.

Ubiquitous chips

As the years passed, the personal computer revolution took hold.

Microprocessors are now ubiquitous. But Ted believes the breadth of their versatility is still under-appreciated.

"One of the things I fault the media for is when you talk about microprocessors, you think about notebook and desktop computers.

"You don't think of automobiles, or digital cameras or cell phones that make use of computation," he says.

Ted launches into an awed analysis of the processing power of digital cameras, and how much computing horsepower they now feature.

Like a true technologist, the things that interest him most lie at the bleeding edge of electronic engineering.

Attempts to make him elevate his personal achievements or evaluate his place in history are simply laughed off.

Ted Hoff (far left) receives the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 2010

Instead, Ted would rather talk about his present-day projects.

"I have a whole bunch of computers here at home. I still like to play around with micro-controllers.

"I like to programme and make them solve technical problems for me," he says.

But if Ted refuses to recognise his own status, others are keen to.

In 1980 he was named the first Intel Fellow - a position reserved for only the most esteemed engineers.

Perhaps his greatest honour came in 2010 when US President Barack Obama presented Ted with the National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

His name now stands alongside other winners including Gordon Moore, Robert Noyce, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Ray Dolby.

Like them, he helped shape the world we live in today.