A brief history of hacking

- Published

Sony has suffered a series of attacks by a variety of hacking groups

The world is full of hackers, or so it seems. In the past few months barely a day has gone by without news of a fresh security breach.

Multi-national companies have been left counting the cost of assaults on their e-mail systems and websites.

Members of the public have had their personal information stolen and pasted all over the internet.

In the early decades of the 21st century the word "hacker" has become synonymous with people who lurk in darkened rooms, anonymously terrorising the internet.

But it was not always that way. The original hackers were benign creatures. Students, in fact.

To anyone attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during the 1950s and 60s, a hack was simply an elegant or inspired solution to any given problem.

Many of the early MIT hacks tended to be practical jokes. One of the most extravagant saw a replica of a campus police car put on top of the Institute's Great Dome.

Over time, the word became associated with the burgeoning computer programming scene, at MIT and beyond. For these early pioneers, a hack was a feat of programming prowess.

Such activities were greatly admired as they combined expert knowledge with a creative instinct.

Boy power

Those students at MIT also laid the foundations for hacking's notorious gender divide. Then, as now, it tended to involve mainly young men and teenage boys.

The reason was set out in a book about the first hacker groups written by science fiction author Bruce Sterling.

Young men are largely powerless, he argued. Intimate knowledge of a technical subject gives them control, albeit over over machines.

"The deep attraction of this sensation of elite technical power should never be underestimated," he wrote.

His book, The Hacker Crackdown, details the lives and exploits of the first generation of hackers.

Most were kids, playing around with the telephone network, infiltrating early computer systems and slinging smack talk about their activities on bulletin boards.

This was the era of dedicated hacking magazines, including Phrack and 2600.

The individuals involved adopted handles like Fry Guy, Knight Lightning, Leftist and Urvile.

And groups began to appear with bombastic names, such as the Legion of Doom, the Masters of Deception, and Neon Knights.

As the sophistication of computer hackers developed, they began to come onto the radar of law enforcement.

During the 1980s and 90s, lawmakers in the USA and UK passed computer misuse legislation, giving them the means to prosecute.

A series of clampdowns followed, culminated in 1990 with Operation Sundevil - a series of raids on hackers led by the US Secret Service.

Group dynamic

But if Sundevil's aim was to stamp out hacking in the United States, it failed.

As connected systems became ubiquitous, so novel groups of hackers emerged, keen to demonstrate their skills.

Grandstanding was all part of the job for collectives like L0pht Heavy Industries, the Cult of the Dead Cow, and the Chaos Computer Club, along with individuals such as Kevin Mitnick, Mafiaboy and Dark Dante.

In 1998, L0pht members famously testified to the US Congress that they could take down the internet in 30 minutes.

Nintendo has also been hit by hackers keen to embarrass the gaming giant

Mafiaboy showed what he could do by crashing the sites of prominent web firms such as Yahoo, Amazon, Ebay and CNN.

Dark Dante used his knowledge to take over the telephone lines of a radio show so he could be the 102nd caller and win a Porsche 944.

Such actions demonstrate how hackers straddle the line separating the legal and illegal, explained Rik Ferguson, senior security researcher at Trend Micro.

"The groups can be both black or white hat (or sometimes grey) depending on their motivation," he said.

In hacker parlance, white hats are the good guys, black hats the criminals. But even then the terms are relative.

One man's hacker could be another's hacktivist.

Worldwide threat

If hacking was a business born in the US, it has gone truly global.

"In more recent times, groups emerged around the world in places as far flung as Pakistan and India, where there is fierce competition between the hackers," said Mr Ferguson.

In Romania groups such as HackersBlog have hit various companies. In China and Russia, many hackers are believed to act as proxies for their governments.

Now, in 2011, it is hacker groups making the headlines once again.

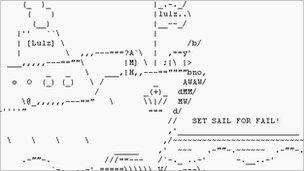

The Lulz Security hacker group pays homage to early computing with an ASCII image on its website

Two in particular, Anonymous and Lulz Security, have come to prominence with high profile attacks on Sony, Fox, HBGary and FBI affiliate Infragard.

"These stunts are being pulled at the same time as national governments are wringing their hands about what to do in the event of a concerted network attack that takes out some critical infrastructure component," said veteran cyber crime analyst Brian Krebs.

"It's not too hard to understand why so many people would pay attention to activity that is, for the most part, old school hacking - calling out a target, and doing it for fun or to make some kind of statement, as opposed to attacking for financial gain," he said.

A current favoured practice is to deface websites, leaving behind a prominent message - akin to the graffiti artist's tag.

According to Zone-H, a website which monitors such activity, more than 1.5 million defacements were logged in 2010, far more than ever before.

2011 looks like it will at least reach that total.

The sudden growth in the number of hackers in not necessarily down to schools improving their computing classes or an increased diligence on the part of young IT enthusiasts.

Rather, the explosion can likely be attributed to the popularity of Attack Tool Kits (ATKs) - off the shelf programs designed to exploit website security holes. Such software is widely available on the internet.

Bruce Sterling, with his future gazing hat on, has a view of what that will mean.

"If turmoil lasts long enough, it simply becomes a new kind of society - still the same game of history, but new players, new rules," he wrote.

And perhaps that is where we are now. Society's rules are changing but we're not sure who is doing the editing.

- Published6 June 2011

- Published7 June 2011

- Published2 June 2011

- Published3 June 2011

- Published7 February 2011