Hoax: From the Hitler diaries to gay girl in Damascus

- Published

- comments

Konrad Kujau convinced journalists he had Hitler's diary

Has the web made it easier to fool the world and journalists in particular? The answer seems obvious after a number of recent web hoaxes.

The famous New Yorker cartoon, external now needs updating to "on the internet nobody knows you're not a Syrian lesbian", after the gay chronicler of the Syrian uprising turned out to be a bearded American living in Edinburgh.

As plenty of reporters have discovered in this and previous cases, it is getting ever harder to verify the identity of someone who comes to you with a great story. The web provides a brilliant platform for a dissident in a repressive state or a whistleblower inside a corrupt corporation to tell the world the truth without revealing their own identity.

But in the online world, how do reporters go about the process of checking that such sources are genuine? In the case of the gay girl in Damascus, journalists did carry out interviews with the blogger, but they were conducted via email. Oh for the days before the web, traditionalists cry, when reporters went out and met people face to face and such hoaxes were impossible.

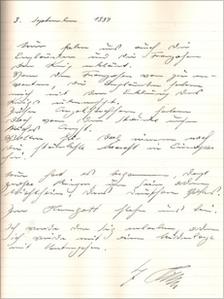

Not so fast. Just take a look at the document I've posted here. It's a page from Hitler's diaries, a massive scoop which I offer to readers of this blog before anyone else gets it.

I found this valuable document when rooting about in my attic over the weekend, and let me swiftly come clean. It's not actually Hitler's diary, it's a fake - or even worse, a fake of a fake.

It dates from 1985, when I was a young producer working for BBC News. Because I spoke some rudimentary German, I was sent to Hamburg to interview the man behind what was probably the most spectacular hoax of the last century. Konrad Kujau had succeeded in fooling first Germany's Stern magazine and then Britain's Sunday Times and America's Newsweek with his forgeries of Hitler's Diaries.

He was in prison awaiting sentencing after a trial which saw both him and a Stern journalist convicted of forgery and fraud. As we completed the interview, I handed over my notebook and he sketched out an entry for 3rd September 1939, the day the war with Britain began.

In John Simpson's report at the end of the trial - he'd been diverted to some breaking news story in the Middle East so couldn't make it to the interview - you see Konrad Kujau sign Adolf Hitler at the bottom of the page.

Kujau was a showman, and skilled at manipulating his contact, the journalist Gerd Heideman, who was something of an obsessive when it came to Nazi memorabilia. The forgeries were pretty crude, made on modern paper and full of historical inaccuracies. But they fooled not only some very experienced journalists but the distinguished historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who vouched for their authenticity - until a chaotic press conference when his doubts emerged.

Now just imagine that the same story emerged today from some anonymous blogger who put his documents online. The web, which makes it easier to spread stories true or false, also makes it easier to check their veracity. Surely the combined resources of bloggers, scientists, and world war two buffs would quickly discover the gaping holes in the story, long before a mainstream publication decided to go to press?

So we shouldn't be too sniffy about modern journalism and its inability to spot a hoax. After all, the real identity of the gay girl in Damascus was unveiled far more rapidly than the name of the man behind the Hitler Diaries. Though most of that detective work was done not by mainstream journalists but by bloggers who knew the Middle East and felt something about the Syrian posts did not ring true.

And that's what's both risky and rewarding about journalism in the networked era. There's far more information - true and false - coming at us to process, but there is also far more help available to sort the fool's gold from the real thing.