Graphene technology moves closer

- Published

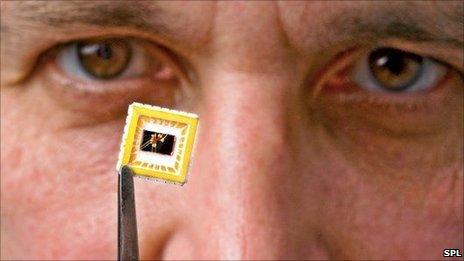

Graphene transistor (pictured) has now been integrated onto a single platform

Graphene is a "wonder material" waiting to happen.

Since this super-conductive form of carbon, made from single-atom-thick sheets, was first produced in 2004, it has promised to revolutionise electronics.

But until recently, it existed more in the realm of science than technology, with limited production techniques and only theoretical applications.

Now a couple of breakthroughs are promising to take graphene out of the lab and into real devices.

The first relates to how it is made.

Currently graphene is "grown" at sweltering temperatures using chemical vapour deposition.

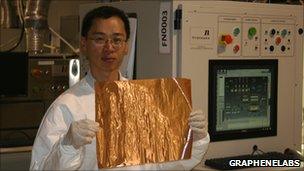

Graphene is "grown" at sweltering temperatures of 1000C

"In the process, a mixture of gases is passed above the catalyst metal - a piece of copper foil or thin nickel film - heated to about 1000C," said Dr Daniil Stolyarov, chief technology officer at New York-based Graphene Laboratories.

"Methane molecules decompose on the surface of the metal and release carbon atoms, which then assemble into a graphene film."

The system is complex and relatively low yield.

Now researchers at Northern Illinois University (NIU) have found a much easier way to manufacture high volumes of graphene - by burning magnesium in dry ice.

The scientists say that the method is simple, faster and greener.

Reporting their findings in the Journal of Materials Chemistry, the team revealed that it had managed to produce "few layer" graphene, several atoms thick.

The NIU discovery happened as a by-product of research into creating carbon nano-tubes.

"It surprised us all," said Narayan Hosmane, professor of chemistry and biochemistry.

Faster chips

The second major breakthrough exciting materials scientists centres on a possible application for graphene.

Its conductive properties are well known and it has long been the vision of chip designers to construct graphene-based processors.

IBM made early inroads in 2010 when it created a basic graphene transistor.

This month, the company announced that it had gone a step further, integrating it into a circuit known as a broadband frequency mixer - an essential component of TVs, mobile phones and radios.

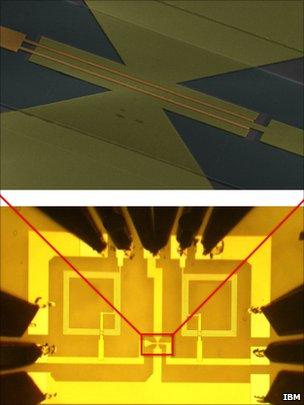

First-ever integrated circuit with a graphene transistor

"When a radio station broadcasts at a high frequency through space, the wave is then received by your radio, but the high frequency cannot be heard, so it must be converted into a low frequency wave that we can hear," the lead scientist of the project, Dr Phaedon Avouris, told BBC News.

IBM calls its research an important milestone for the future of wireless devices.

Perhaps more importantly, it demonstrates the capability of graphene integrated circuits.

Previously, scientists had experienced difficulty preserving the integrity of the material during the silicon etching process. Getting it to work alongside other chip materials had also proved problematic.

"Our work demonstrates that graphene can be used as practical technology, that it's no longer some individual material," said Dr Yu-Ming Lin, one of the scientists on the project.

"This is the first wafer-scale production of graphene-integrated circuit - and we've shown that graphene can be integrated with other elements to form a complete function, which enables higher performance and more complex functionalities in a circuit."

The results appear impressive.

In their paper published in the journal Science, the team explained that the circuit could operate at high frequencies of up to 10GHz (10 billion cycles per second), and at temperatures of up to 127°C.

Big surprise

IBM's work surprised many - even the physicist behind the material's discovery.

"I never suspected we would get there so fast," said Dr Konstantin Novoselov of Manchester University.

He is the man who, together with a colleague Dr Andre Geim, first produced this highly conductive, extremely strong and transparent material in 2004.

The two scientists, both originally from Russia, managed to extract graphene while experimenting with plain old sticky tape and graphite, commonly used in pencils.

The pair won the prestigious Nobel Prize for their breakthrough.

"This integrated circuit is a logical step forward, and it's somewhere in the middle between the first experiments and real-life applications," said Dr Novoselov.

"But I was surprised to see that someone managed to do it that quickly."

Other applications

Electronics giants as well as small labs have been eyeing graphene's future prospects, hungry for smaller, faster, thermally stable and more powerful electronic components.

Yu-Ming Lin (l) and Phaedon Avouris (r) are part of the IBM team working with graphene

Korea's Samsung has invested heavily into graphene research, and the Finnish firm Nokia has just announced its plans to team up with partners - among them the two Nobel-prize winners - to explore graphene opportunities.

Besides electronics, graphene could be used in optics and composite material applications.

A number of graphene-based prototypes have already been developed in labs around the world - and it seems that possibilities are almost endless.

It has also proven a hit with biologists - as the most transparent, strongest and most conductive material on Earth, graphene could be an ideal candidate for Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Samsung has promised to release its first mobile phone with a graphene screen in the near future.

Professor Andrea Ferrari of Cambridge University says that besides being totally flexible, a touch screen of a phone or a tablet made of graphene could even give you "sensational" feedback.

"We went from physical buttons to touch screens, the next step will be integrating some sensing capabilities," says Professor Ferrari.

"Your phone will be able to sense if you're touching it, will sense the environment around - you won't have to press a button to turn it on or off, it will recognise if you're using it or not."

Also, he said, one day we might not need to carry around GPS devices - along with other graphene-based sensors, they could be woven into our clothes.

"Besides GPS, you could have something that will monitor your heart rate for instance - and it'll be integrated into the fabric," explains Professor Ferrari.

And graphene could even help airplanes "communicate" with pilots.

The scientist explained that electrical properties of graphene change depending on the strain it is subjected to - like when there are strong winds, for instance.

So the casing of the plane would be able to sense if it is under great or small stress, and feedback the information directly to the cockpit, without the need for additional sensors.

- Published5 October 2010