When the home help is a robot

- Published

Machines are tested on their ability to carry out domestic tasks

In the future, we will have robots in our homes. They will do all the dirty and boring jobs that we don't want to do because we've got better things to do such as sip cocktails or play with our children.

Or at least that's what many films, novels and media articles have promised. Reality is taking some time to catch up. So far, the only domestic robots enjoying significant success are toys or, in a distant second place, those that vacuum the floor.

Intelligent machines that can greet our guests, serve drinks and do the laundry are still the stuff of science fiction.

But progress is being made.

Home work

Some of that progress was on display at the 2011 RoboCup. Although most of the tournament is about getting intelligent machines to play football, one of its constituent contests is for robots designed to interact with people in their homes.

RoboCup@Home pits machines created in labs around the world against each other to see which can do the best job of serving their human masters.

The competition sets tough goals because of what robots will have to do when they start to live alongside us, said Dr Sven Wachsmuth from the University of Bielefeld, who oversees the RoboCup@Home competition.

"It's about human-robot interaction and skills," he said. "They need to communicate with humans and navigate their environment."

The competition is not about producing a better robotic floor mopper or carpet sweeper. For AI researchers, those problems are not interesting or difficult enough.

"Those tasks do not need human-robot communication," he said. "But there are other tasks that rely on that."

It's those tasks that demand some interaction between robots and people that the RoboCup@Home tests.

"We test if the robot is friendly and helpful and if it is it polite to me," said Dr Wachsmuth. "Does it show the natural interaction that we are used to?"

Object lesson

The contest takes place in a denuded apartment made up of several rooms including bedroom, kitchen, hall, utility room and living room.

Robots are allowed to explore this mock home to create their own mental map and get to know the fixtures distributed around it - washing machine, table, shelves, cupboard, microwave - and the objects that adorn it - crackers, flowers, shoes, a tea box, crisps and soda.

To do the mapping and object spotting, many of the robots taking part in the RoboCup@Home had adopted and adapted the Kinect sensor produced for the Xbox 360 console.

The robots get to know a limited set of the objects people use

The sensor array used in the gadget proved very useful when robots were finding their way around or looking for a specific object.

Dr Xiaoping Chen, who heads the Wright Eagle robot project at the University of Science and Technology in China, said there was another reason the Kinect is proving attractive.

It is cheap.

Sensors that can map the world with the fidelity of the Kinect used to be very expensive, he said. But cheaper parts will mean more robots.

"Price is a very important factor if robots are to get into everyone's homes," said Dr Chen.

The tests the robots are asked to perform are contrived to catch them out and see if they can work out what to do. For instance, in one test a human asks the robot to retrieve a drink from the kitchen.

Unbeknownst to the robot there are no cans of that brand of drink in the fridge. When it finds this out, the robot must decide what to do. Should it take what it finds even though it knows it is wrong or ask what else that person would like instead?

Other tasks test the robot's ability to deal with the messy realities of human life such as sorting washing.

Humans find these tasks easy if dull, but for robots, unschooled in social niceties and without any evolutionary history to draw on, working out what to do is tricky.

"There are so many things we take for granted as humans," said Dr Nathan Kirchner, who heads the University of Sydney's RobotAssist team. "But when you get a machine to do it there's nothing for free. It has to learn every action."

Small steps

Some robots did a good job of navigating around the mock apartment used in RoboCup@Home

The computation involved in working out what is happening and what to do about it is formidable. The RoboCup@Home contest showed off some of those different approaches. For instance, the Nimbro team from the University of Bonn based the decision making system of their Cosero robot around probabilities.

In all situations it weighs up its options given where it is, the actions possible in that place, and measures it against what it has been asked to do.

The competition showed that progress is being made. Some robots navigated the mock apartment well, did a good job of recognising people and guests and were not fooled by the tricky questions.

Technology is developing rapidly, said Dr Wachsmuth. So much so that every two years the rules for RoboCup@Home have to be revised because the robots have caught up and mastered the tasks they were presented with in earlier years.

"We're making it more complicated every time," he said.

Despite this and the success of many of the robots taking part, Dr Wachsmuth believes that other types of robots will appear in homes before robot valets. Robots that help with communication and telepresence are more likely to turn up first.

"You might have a robot dog rather than a real dog so you can turn it off when you go on vacation," he said.

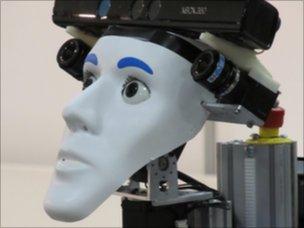

Some robot makers encourage interaction by giving their creations a human face

What is clear is that robots in our homes that know what we want and can help us get it are going to be more important. Demographics tells us that, said Dr Chen.

"China, like many other places, is changing from an aging society to an aged society," he said. "It's changing dramatically and we need to adapt to that."

"We want to make a robot think like people and live alongside people so it can aid people," he said.

"We do not think of a robot as a tool, we think of it as a friend."

- Published11 July 2011

- Published8 July 2011