Click listeners test 'filter bubble'

- Published

Click listeners shared their search results through the show's Facebook page.

How personalised is the web? That's the question that Click listeners all over the world have been helping us answer.

The worry is that we are cosseted in an information cocoon based on personalised results from search engines, automated recommendations from online bookstores and social networks that feed us gossip and news only from our innermost circle of friends.

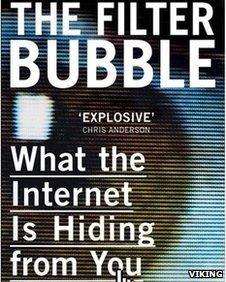

On Click radio a few weeks ago, we interviewed Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You, external. He told us "People don't use Google as a tool which is personalised; they don't expect it to deliver a subjective version of the world. Google has this whole mythology around page rank, this algorithm that collects the truth from all of these different web sites and democratically arrives at the right answer and that's not really how the search engine works any more."

Mr Pariser is concerned that there is an illusion of objectivity in Google search results, when in fact they are filtered according to what we are most likely to click on when we browse the all important front page of results. He cites the hypothetical conspiracy theorist who searches for '9/11 bombings' and only sees other conspiracy websites rather than articles that debunk the crackpots.

Before we spoke to Eli Pariser, we asked Click listeners to put his theory to the test by Googling the same word whatever their location, browser, platform, device or language. After much consideration in the office, we came up with the word 'platform'. It is a widely used word, largely politically neutral and with multiple meanings whether pertaining to computing, railway stations, oil drilling or outlandish shoes from the 1970s.

We suggested that listeners try the same search with the personalisation settings on or off and also logged in and out of Google. To share their results, we invited our volunteers to post screen grabs to our Facebook listeners group, external.

Our Facebook group was soon deluged with screen grabs. As I write this, three weeks on, they are still coming in. To date, over 150 Click listeners have taken part from 29 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, the USA, South America and Oceania. With nearly 300 individual screen grabs to pore over, Click team member Nelida Pohl was enlisted to try and make sense of them.

If Eli Pariser is correct then one might expect significant variations in search results, based on each user's own interests. However Nelida says "the same websites showed up over and over again, especially within countries. In an individual country, most had the same seven or eight websites in the first five hits and most of the differences I found were between countries".

Results

Participants were asked to search for the word 'platform' using Google

In all countries, the Wikipedia entry for 'computing platform' came up. This was mostly in English, but also in other languages depending on the country. In the UK, most of the top five searches included an intermediary of the Co-operative Bank called 'Platform'. There was a software company called 'Platform' in the US. The listings also included the electoral platform of the American Libertarian Party. Google Canada listed the equivalent pages for country's Green party. In Australia, a common return was a modelling agency.

We were surprised to find that it did not make much difference whether users were logged in or out of Google or whether they had disabled the personalisation settings. When we put these initial results to Eli Pariser on our Click programme a few weeks ago, he suggested that the apparent lack of personalisation may have been down to the word we chose. "Google handles different queries quite differently from each other and there are some queries that mostly seem to return similar types of results and others that you'll see different results depending on different people."

This experiment was part of a series on openness we have been making in association with the Open University. In a specially recorded podcast on the subject, Tony Hirst of the University's Department of Communication and Systems joined me to discuss the results and provide expert analysis.

Eli Pariser suggests that users are seeing their own world view reflected online

Even though within countries the same links tended to appear in the top few results, Tony Hirst believes the changes in rankings, however subtle, should not be understated and that they are evidence of personalisation. "If you have just a slight change in the ordering, particularly something that might bubble up from eighth to third or fourth on the screen where you're far more likely to see it, then just that simple change in ordering might have a huge influence on what you click on".

The Filter Bubble suggests paternalism to Google's search algorithms; that we are always fed just what we want to read. Tony Hirst says that relevance is a key part of Google's offering but equally it is not good for business to overdo the filtering. "It's in Google's interest to keep people engaged and to spend time looking at the results page where they have adverts. So if they can give results that are of interest to you whilst not necessarily directly reinforcing your opinion, you may go back to that results page and click on one of those links".

On Click, we like to put theories to the test, no matter how persuasive they appear at face value. With the help of our listeners we've done that with The Filter Bubble. Of course our survey is far from scientific; the sample size is relatively small and is only based on one search term. It does not refute Eli Pariser's hypothesis. In fact his book serves a valuable purpose by reminding us that the services we use online are becoming increasingly personalised and that there is more to search results than purely objective page rank.

I have been blown away by the enthusiasm of Click listeners to go to the trouble of taking all those screen grabs and posting them on Facebook. Thanks to some impressive Click-style crowd-sourcing, we have a slightly better idea of whether or not we really are all living in the filter bubble.

- Published22 June 2011

- Published22 June 2011