3D interactive journey into the Great Pyramid of Khufu

- Published

Interactive 3D film about a theory of the construction of the Great Pyramid of Khufu in Egypt has now migrated on to the home desktop

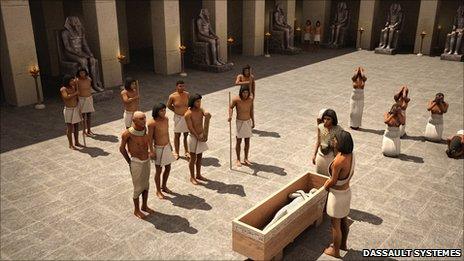

A mouse click - and a member of a pharaoh's burial procession turns around.

One more click - and the animated figure invites you inside the snaking, narrow corridors of one of the world's most magnificent structures - the Great Pyramid of Khufu, also known as the Great Pyramid of Cheops.

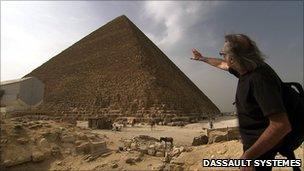

Peering into the screen through his funky red and blue 3D glasses, ancient Egypt enthusiast Keith Payne is gripped by the centuries-old story unfolding before his eyes as if through a time-travel lens.

"This is amazing!" he says. "I think that being able to use a 3D simulation tool to explore Khufu's pyramid is really a whole new way of both learning and teaching.

Jean-Pierre Houdin's controversial theory is totally different from all other hypotheses

"Being able to pause the narration and virtually take control of the camera to go anywhere in the scene and explore for yourself, and then return to the documentary where you left off is a way of learning that was never really available before now."

This interactive journey, first presented to the public in a 3D theatre in Paris, has now migrated onto the home desktop.

To watch the film, users simply download a plug-in and don a pair of 3D glasses - although the software gives the sensation of depth without them too, to a lesser extent.

And it works with 3D TVs, too.

Controversial theory

With help of cutting-edge 3D technology, the video lets users take a peek inside the 146m-high Great Pyramid, the last of the seven wonders of the ancient world still standing.

The scene appears as it might have 45 centuries ago - full of the loyal people of the second ruler of the fourth dynasty.

But the film is not pure entertainment - besides the educational aspect, it tries to explain one of the theories behind the pyramid's construction.

Lying north of modern-day Cairo, the largest and oldest of the three pyramids of the royal necropolis of Giza is believed to have been built as Khufu's tomb.

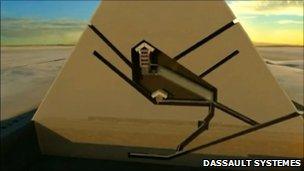

Inside, it contains three burial chambers - one underground, a second known as the Queen's Chamber which was possibly intended for the pharaoh's sacred statue, and the King's Chamber.

This latter is located almost exactly in the middle of the structure, and it is there where the pharaoh's granite sarcophagus lies, but no mummy has ever been found.

What we don't know is how this colossal monument, made of two million stone blocks that weigh an average of 2.5 tonnes each, was actually built.

The interactive 3D film outlines one hypothesis.

The enigma of the Great Pyramid's construction has intrigued people for centuries and sparked many theories

"It is a theory that explains how the Egyptians, who had no iron, no wheels and no pulleys, were able to build such a massive structure," says the project's interactive director Mehdi Tayoubi from French software firm Dassault Systemes, external.

"Most of all, it explains how they managed to get huge beams weighing around 60 tonnes each all the way up to the King's Chamber."

The idea has been drafted by French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin.

It differs sharply from another popular theory which suggests that ancient engineers used an outside stone ramp, spiralling its way to the top. No physical evidence to support such a system has ever been found.

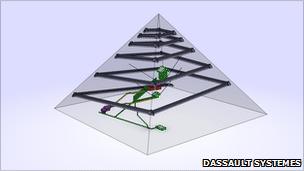

Instead, Mr Houdin insists that the ramp was inside the pyramid - hence it is invisible from the outside.

The computer simulations done with Dassault Systemes seem to support this belief.

Djedi, a tiny robot, has been exploring the Great Pyramid of Khufu for the past two years

But not everyone agrees. Professor of Egyptology at Harvard University, Peter Der Manuelian points out that this theory too lacks solid proof.

"Mr Houdin has worked very hard to try to explain many of the features inside the Great Pyramid, he's certainly a dedicated researcher," he says.

"But until we can do some non-invasive means of confirming or denying his hypothesis, we will have to leave it as just a theory."

But the architect insists that there is some scientific backing to his thoughts.

For instance, in 1986 a French team used microgravimetry - a technique that measures the density of different sections of a structure to detect hidden chambers.

The resulting scan showed a curious pattern - a hollow that seems to wind the walls up the inside of the pyramid.

Infrared imagery

And it is possible to get even more evidence, says Mr Houdin.

The theory suggests ancient builders used an internal and not external ramp

Cracking the ancient monument open not being an option, his team decided to measure the reaction of the pyramid to exterior factors - such as heat.

To do that, they got in touch with specialists in infrared imagery from the University Laval in Canada who have decided to set up special cameras around the pyramid.

"In Egypt, air temperatures vary greatly between day and night - and rocks in the pyramid react accordingly," explains Mr Houdin.

"If the pyramid is a solid structure, then according to our computer simulations, in the summer at noon it will be hotter at the top as there's less mass, and cooler at the bottom, where the cold ground helps to cool it from below.

"But if there's an internal ramp, it will be the other way around - the pyramid will be cooler at the top."

Setting up a few cameras may seem simple enough, but for this next step to succeed, the joint international venture must be okayed by the Egyptian authorities - who have so far been reluctant to give any kind of positive response.

Djedi robot

Besides the infrared proof, one other explorer could also help reveal what is hidden in pharaoh Khufu's eternal resting place.

Meet Djedi - a tiny robot that has been exploring the pyramid for the past two years.

Its name, although reminiscent of the Star Wars warriors, belongs to an ancient Egyptian magician whom Khufu consulted when building the pyramid.

The project is a separate one from Jean-Pierre Houdin's construction analysis, but has also been developed with help of Dassault Systemes - and in collaboration with an international team of researchers.

Djedi's mission is to continue the work of its predecessors.

After the pyramid's main chambers were discovered, researchers were puzzled by one interesting fact.

They found two straight narrow shafts 20cm by 20 cm that connected the King's Chamber with the outside world which were thought to have been used for ventilation.

There are two similar shafts that go from the Queen's Chamber, but never reach the walls, mysteriously stopping seemingly nowhere.

In 2002, a robot crawled to the stone in the end of the shaft and boldly drilled a hole in it, transmitting live images so the entire world could witness the moment of unveiling.

But that mission failed.

The King's Chamber sits in the middle of the Great Pyramid with the Queen's chamber below it

A second door, unseen for more than 4,000 years, blocked the way - and Djedi now has to drill a hole in that too.

"The Great Pyramid is a truly unique and wonderful structure - the shafts and "doors" do not exist in any other ancient Egyptian building," says the project leader Shaun Whitehead.

"Finding out why they are there will give us a greater insight into the techniques and motivation of an amazing civilisation from 4,500 years ago."

The robot crawls forward as a mechanical inchworm, armed with an endoscopic "snake camera" that can look into difficult to reach spaces.

It is also equipped with a drill, hopefully long enough to reach and pierce the second door.

And it has already sent back some exciting images.

In May 2011, Djedi found what looked like ancient graffiti in-between the two doors.

As these two separate, but interrelated projects progress, we may be on the very edge of uncovering some our past's greatest secrets.

The 3D film takes viewers back to ancient Egypt, as it was 45 centuries ago

- Published9 June 2011

- Published25 May 2011