Is technology to blame for the London riots?

- Published

Did social media and mobile telecommunications fuel this weekend's violence in London?

A number of politicians, media commentators and members of the police force have suggested that Twitter and BlackBerry Messenger, in particular, had a role to play.

Undoubtedly, some of those involved chose to chronicle their exploits live - from the midst of the action - using mobile phones.

A few were apparently even foolish enough to upload pictures of themselves posing proudly with their looted haul.

Others offered suggestions for where might be good to attack next, leading the Met's deputy assistant commissioner, Steve Kavanagh to say he would consider arresting Twitter users who appeared to incite violence.

But some experts fear the extent to which technology is to blame may have been overstated.

Misquoted

In its coverage, the Daily Mail quoted one tweeter, AshleysAR as follows: "Ashley AR' tweeted: 'I hear Tottenham's going coco-bananas right now. Watch me roll."

However, AshleysAR's full, unedited quote on Twitter reads: "I hear Tottenham's going coco-bananas right now. Watch me roll up with a spud gun :|".

Suddenly the tone of the message becomes markedly less sinister. Ashley later threatens to join in with a water pistol.

Despite the claim of Tottenham MP David Lammy that the riots were "organised on Twitter", there is little evidence of their orchestration on the site's public feeds.

Looking back through Saturday night's postings, DanielNothing's stream offers some promise of substantiating the theory with his comment: "Heading to Tottenham to join the riot! who's with me? #ANARCHY".

But it is followed soon after by: "Hang on, that last tweet should've read 'Curling up on the sofa with an Avengers DVD and my missus, who's with me?' What a klutz I am!"

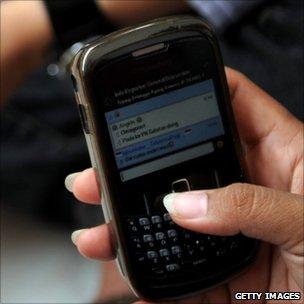

BlackBerry's BBM requires users authenticate their contacts with a PIN

Another user - Official Grinz - appears to have been the first person to tweet the words "Westfield riot", referring to the west London shopping centre. Although his message seems to be tongue in cheek and there is nothing to suggest that he was more than observer, commenting on events as they unfolded on television.

The subject of a Westfield riot became widely discussed, but ultimately failed to materialise in the real world.

So why is the ratio of apparent incitement to action so low?

Freddie Benjamin, a research manager at Mobile Youth, believes that much of the online noise is just that.

"Once someone starts posting on a BBM group or Twitter, a lot of young people try to follow the trend," he told BBC News.

"They might not join the actual event, but they might talk about it or use the same hashtag which makes it sound like there is a lot more volume."

Such postings build what Mr Benjamin refers to as "social currency", elevating the messenger's sense of belonging to a group.

Private business

Away from Twitter's very visible feeds, there are perhaps more credible reports that rioters were using private communication systems to encourage others to join the disorder.

Following Saturday's trouble in Tottenham, a number of BlackBerry users reported receiving instant messages that suggested future riot locations.

BlackBerry's BBM system is known to be the preferred means of communication among many younger people.

Users are invited to join each other's contacts list using a unique PIN, although once they have done so, messages can be distributed to large groups.

BBM is both private and secure, partly due to the phones' roots as business communication devices.

For that reason it is hard to evaluate how much information was coming out of the riots or how many people were suggesting alternative targets.

But despite the closed nature of BlackBerry Messenger, police may still have a chance to examine some of the communications that took place.

Research in Motion, which makes Blackberry phones, issued a statement in which it promised to work with the authorities.

It pointed out that, like other telecoms companies, it complies with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) which allows law enforcement to gain access to private messages when they relate to the commission of a crime.

Recruiting tool

What will concern investigators most is the extent to which recipients acted on any messages sent out.

Dr Chris Greer, a senior lecturer in sociology and criminology at London's City University believes that smartphones will have aided those involved, but are unlikely to have persuaded reluctant recruits to join the rioting.

"I don't think it is having any impact on the motivation to protest in the first place," he said.

"But once people have mobilised themselves and decided to take to the streets it is certainly much easier to communicate with each other."

Dr Greer pointed to the example of the 2009 G20 riots in London.

A report into the police handling of the protests, produced by Her Majesty's Inspector of Constabulary (HMRC) found that technology had aided the rioters more than the police, he explained.

"Their methods of communicating with each other or pointing out where the police were at any given time and therefore where the protesters shouldn't be, and basically organising themselves was so much more sophisticated than the police."

It may turn out, after a more careful examination of the various messages being pinged around, that this was indeed a social networking crime spree.

The Met has indicated it is ready to act on any information it finds.

But that will take time and a more methodical study.

The extent to which investigators are able to sift out genuine rioters from the internet 'echo chamber' and then bring real world prosecutions will provide valuable lessons, both about the use and abuse of technology, and also law enforcement's capacity to deal with it.