Will we all be tweaking our own genetic code?

- Published

WATCH: Professor George Church explains his vision for the future of genetics

You have to wonder what's going on in the DNA of Harvard genetics professor George Church.

What extra bit of code does he have that the rest of us don't? If genes tell the story of a person's life, then some altered sequence of 'A's, 'C's, 'G's and 'T's must be at play, because his brain works like almost no one else's.

About 30 years ago, Prof Church was one of a handful of people who dreamed up the idea of sequencing the entire human genome - every letter in the code that separates us from fruit flies as well as our parents. His lab was the first to come up with a machine to break that code, and he's been working to improve it ever since.

Once the first genome was sequenced, he pushed the idea that it wasn't enough to have one sequence, we needed everyone's. When people pointed to the nearly $3bn price tag for that first one, he built another machine.

Now, the cost is down to below $5,000 per genome, and Prof Church says we're quickly heading toward another 10- or 20-fold decrease in price - to roughly the cost of a blood test.

Genes: read, write, edit

To Prof Church, routine whole-genome sequencing will herald the beginning of a new era as transformative and full of possibilities as the Internet Age. But this is not just about insurance companies wanting to have every customer's entire genome in their files.

For Prof Church sees this only as a beginning of the project, rather than the culmination of three decades of work.

Helping to develop the machines to sequence the human genome was Prof Church's first big achievement

He's pointing to at a bigger goal: Now that reading DNA code is almost simple, he wants to write and edit it, too.

He envisions a day when a device implanted in your body will be able to identify the first mutations of a potential tumour, or the genes of an invading bacteria. You'll be able to pop an antibiotic targeted at the invader, or a cancer pill aimed at those few renegade cells.

Another device will monitor your outside environment, warning you away from sites that pose a health risk.

A range of genetic disorders will be identified at birth, or even conception, and tiny, preprogrammed viruses will be sent into the body to penetrate compromised cells and correct the damage. Changing the adult body at the first signs of illness will be just as easy, he predicts.

There's no reason, Prof Church says, why people won't be able to live to be 120, and then 150.

"There used to be this attitude: here's your genetic destiny, get used to it," Prof Church says. "Now the attitude is: genetics is really about the environmental changes you can make to change your destiny."

Democratic science

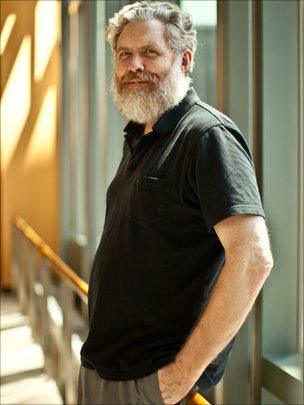

Standing at 1.93m, with a bushy reddish-grey beard, George Church is hard not to notice. The 57-year-old is both imposing and unassuming. There's an awkwardness to Church, like an 8th grade boy after a summer growth spurt, and an openness that makes him easy to like. His manner is the same with a Harvard faculty colleague as with the technician operating a machine he helped design.

This democratic instinct comes through in his science. Church advises 20 of the 30-or-so advanced genomics companies in the United States, but his heart is clearly in academia, doing basic science that helps everyone.

As he pushes for the mapping of more and more complete genomes, he also pushes to make those genomes public, so researchers can learn about medical conditions by comparing them. He's put 11 up on the web already, including his own, and is aiming for 100,000 more.

Once thousands of people with diverse backgrounds have made their genomes and health status public, researchers will be able to delve into a wide range of diseases and disorders, from schizophrenia to heart disease, diabetes to learning disabilities, looking for patterns.

"You bring down the price and many blossoms bloom," he says.

Prof Church doesn't want to make these discoveries himself. The pace of that kind of science is too slow for him, and not driven by technology.

Prof George Church at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard

'Evolution on steroids'

There's a climate-controlled room in the middle of Church's generous lab space, where a small tray shakes back and forth, jostling pellets of E. coli DNA.

In a four-hour production process, researchers can turn on or off a single base pair of that DNA, or whole regions of genes to see what happens. The goal is to find a way to improve production of industrial chemicals or medications, or to test viral resistance.

"You could think of this as driving evolution to very rapid rates," Church said. "Sort of evolution on steroids."

The machine is a second-generation Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) machine, built with help from industry; the first one, which sits across the street not far from Church's corner office was a doctoral student's PhD thesis. Another thesis project sits just on the other side of the wall from new MAGE. Called the Polonator, this open-source genome-sequencing machine can read and write a billion base pairs at a time.

These two machines put Church's lab at the forefront of synthetic biology, a burgeoning new field that aims to make things Mother Nature never thought of, like high efficiency, non-polluting fuels, and viruses that can carry cancer drugs safely to a tumour.

With these machines, Prof Church is doing to synthetic biology what he's already done to personalised genomics: making it cheaper, faster and available to everyone.

Take a snip of DNA here, insert a snip of DNA there

Ethical concerns

"He's beginning to transform synthetic biology to a larger scale," says James J. Collins, a professor at Boston University and Prof Church's colleague at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard.

Prof Collins acknowledges that some people will have ethical concerns about scientists writing genetic codes. But, he said, the reality of synthetic biology is nowhere near as scary as the hype. No one is creating doomsday species or humanoids. They're just barely able to create a single new cell, says Prof Collins.

"I think we as a community have a need and a role and responsibility to educate the public as well as to take precautionary safeguards to make sure we're not introducing something that's problematic," says James Collins, who builds his cells with programmable kill switches, so they self-destruct before reproducing or mutating.

George Annas, chairman of the department of health law, bioethics and human rights at Boston University, agrees that it's too early to be troubled by the ethics of synthetic biology. "At this point, we don't know how synthetic biology will turn out or even if it will work at all," he says.

Of the possible fears about new life forms: "I think we're in the realm of science fiction right now," Mr Annas says.

Reality check

Prof Church's optimism about the power of reading and writing DNA is contagious, but not irresistible.

"You need George's imagination and his vision if you're going to do make any progress at all. But you've got to be foolish to think you're going to make as much progress as he [imagines]," Mr Annas says.

American medical care is going broke as it is, he said. Adding more personalised treatment is only going to drive up the cost. And medicine may be able to add years to someone's life, but the quality of those years is unlikely to be good, warns Mr Annas.

Chad Nussbaum agrees.

"There's a statistical chance of being hit by a truck that's going to make it hard to live to 150 no matter how healthy you are," says Mr Nussbaum, co-director of the genome sequencing and analysis program at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, a genetics research institute, where Church is an associate member.

Extreme aging isn't all about genetics, Mr Nussbaum says, it's basic engineering: parts just wear out over time. "It's wonderfully naive to think all we have to do is learn all the genetics and we'll live to be 150."

But Chad Nussbaum says he still admires Prof Church's vision and his "genius."

"It's a great thing to think big and try to do crazy things," says Mr Nussbaum. "If you don't try to do things that are impossible, we'll never accomplish the things that are nearly impossible."

- Published18 August 2010

- Published27 October 2010

- Published23 June 2010

- Published5 July 2011