75 years on from BBC television's technology battle

- Published

Singer Helen McKay took part in trial broadcasts ahead of the official launch

75 years ago on 2 November 1936 the world's first high definition TV service was created.

A momentous occasion, but the road towards it had been rocky, with corporate uncertainty, government intervention, multiple egos and a race against time.

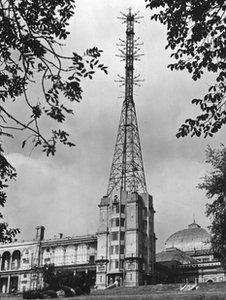

Eventually Alexandra Palace was chosen as the the setting for history to be made.

The location was chosen mainly because of its location, high above London, but also because of the project's time scale.

With a mere 18-month deadline, it was deemed cheaper, easier and quicker to convert an existing building than to build new.

And so 'Ally Pally' - as it was named by an early TV performer Gracie Fields - with its extraordinary TV tower, became the iconic visual for 1930s TV.

Broadcast battle

Then began the race for TV. Two competing systems of television were to be tested for a period of six months in two different studios.

In studio A was the Marconi-EMI system, all-electronic on 405 lines.

It had the advantage of being flexible: three cameras could be accommodated, and most importantly, the cameras could be moved on wheeled dollies to follow the action and to provide close-up shots.

The BBC used the Alexandra Palace studios until July 1981

Studio B housed the Baird system on 240-lines (devised by John Logie Baird), which was a mainly mechanical system, much more limited in range and capacity.

Live announcements were made from a cramped "spotlight studio" which scanned the head and shoulders of the announcer with an intense beam of light.

Physically uncomfortable for the presenter, it also made use of a very delayed form of TV (the Intermediate Film Technique for the cognoscenti).

Under this system, the film passed into a processing tank of cyanide where it was developed, providing a TV picture only 58 seconds later.

Test run

The official opening ceremony was on 2 November 1936.

After the toss of a coin, the pilot programme was transmitted first on the Baird system and then after a brief pause, the entire programme was done again live on the Marconi-EMI system.

So the BBC's second television programme was also its first repeat.

Within three months the decision to go with the Marconi-EMI system was made and the Baird studio at Alexandra palace was closed down.

Baird had been the best of propagandists for the new innovation of television, but as Rebecca West said of him he was "doomed to be the man who sows the seed but does not reap the harvest".

Three years later, on 1st September 1939 World War II loomed and the staff at Alexandra Palace were instructed to switch off the transmitter and close the service down for the duration.

The last programme seen on air was a Mickey Mouse cartoon; when the TV service re-opened on 7th June 1946, its first programme was that very same cartoon.

The Marconi-EMI system was selected over rival technology from John Logie Baird

It was followed the next day with a major outside broadcast of the Victory Parade on the first anniversary of Victory in Europe.

Moving out

BBC television quickly outgrew the two original studios at Alexandra Palace.

Additional studios were provided at Lime Grove and the Television Theatre in west London, and then in 1949 the BBC purchased a 13.5 acre site at White City for a future "Television Centre".

News moved to Alexandra Palace in 1954 for a decade or so, and in 1970, the newly-launched Open University had its programme-making base there till 1981.

Thirty years later, and 75 years after television started, much of the original structure is still there and it is now the earliest surviving example of a television station anywhere in the world.

The men and women who worked there took television from a scientific novelty and set it firmly on the path to become the most powerful communications medium of the 20th Century.

We owe a debt of gratitude to the scientists, engineers, production teams and performers who have given us such a wealth of entertainment, information and education over the last three quarters of a century.

- Published2 November 2011