Bee hive hums recorded to monitor insects' health

- Published

Honey bees use vibration to communicate while inside the hive

Monitoring devices are being put in bee hives across Scotland as part of a project to keep an eye on their health.

The monitors record temperature and use a microphone to record the hum the bees make while working and resting.

Already the project has started to show the many different hums bees use to co-ordinate their work.

The project is also helping to work out which environmental forces and factors are behind the decline in bees and other pollinators.

Sound stage

The monitor is the invention of Huw Evans, who swapped his former trade of electronic engineering for beekeeping.

He said the desire to get a better idea of what was happening inside a colony came to him after a few bad experiences with hives on the verge of swarming.

Mr Evans knew of the work done in the 1950s by BBC sound engineer and beekeeper Eddie Woods, who created a device that analysed the sounds made by bees in a hive.

Mr Woods claimed that more than 90% of the inspections beekeepers made of their hives were unnecessary because, most of the time, the bees were fine.

In those cases, all a beekeeper did when he looked through the combs was upset the bees and stunt honey production.

To fine tune his beekeeping, Mr Woods produced a device called the "apidictor" that helped spot when hives needed help because they were sick, running low on stores or close to swarming.

The downside of using the apidictor was that a beekeeper still had to visit a hive and insert a microphone to listen to the hum within.

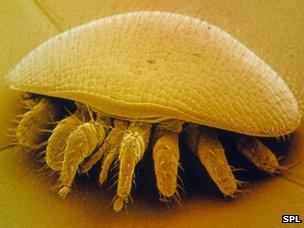

The varroa mite is one of many pests that sap the health of a colony of bees

Mr Evans' monitor updates the apidictor using modern digital signal processors and algorithms designed to recognise different hums. He has set up a company called Arnia to commercialise the device.

"Every job a bee does inside a hive makes a slightly different noise," he said. "So if we can listen to the mass of sound within the hive and possibly dissect that, we can find out a lot about the inner dynamics within the hive.

"We started off looking for swarm prediction but when we began trawling through the data we noticed some other features. The monitor can give an indication of the strength of the hive, the fitness of the hive, how fast the hive is building, their intent to swarm and other such things."

The monitor is a flat black box about the size of an iPhone that regularly measures the temperature of the brood inside a hive and the sound of the bees. This data is regularly sent to a separate master unit, which collates responses from several monitors. It also keeps an eye on rainfall and external temperatures.

Every so often the master unit sends the information it has received from all the other monitors, plus weather data, back to a server via the mobile network.

Noises off

While developing the monitor, Mr Evans has been refining the analytical tools that dissect the different hums in a hive. He hopes these will help the many scientists researching the problems that afflict bees, by giving them hints about what was happening before a colony failed.

Mr Evans is working with the Scottish Beekeepers Association, and the little black boxes are now sitting in about 70 hives across the region.

The data gathered by the monitors is also aiding the research of Chris Connolly from the University of Dundee, who is taking part in theInsect Pollinators Initiative, external- a five-year, £10m project which aims to understand what is causing populations of these insects to dwindle.

Bees were a good indicator of the health of that larger insect population and were much easier to study as they lived inside a hive, said Mr Connolly.

The monitors are sitting in about 70 hives across Scotland

"We have monitors in hives to record how the colony builds in strength throughout the season," he said. "Hopefully, we can correlate that to events that occur on each individual hive, whether a particular treatment knocked bees back or not, and whether the weather and other factors also play a part.

"Bees are so important because they and other insect pollinators produce 30% of the food on our plates."

Communication

Mr Evans was also hopeful that regular monitoring of hive hums would pinpoint when bees were sick and what disease had hit them.

"We've noticed that ill colonies sound different," he said. "We haven't managed to characterise which diseases leads to which sounds but that's work in progress."

As well as helping beekeepers, the work of the hive monitor could also give great detail about a largely unexplored facet of the honey bee's life.

"We know less about acoustic communication than any other type of communication in bees," said Alexandros Papachristoforou, a biologist at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki who studies bees.

"Researchers tend to look at visual communication or chemical communication. They don't pay much attention to sound."

The hum in a hive is generated by the bees shivering their wings and abdomen as they go about their work in the colony. Although bees lack ears, the hum is believed to be very important to the co-ordination of hive activity, because bees often modify wax comb to be a better conductor of vibration.

Sound was hugely important inside the hive where vision was useless and chemical signals took time to propagate, said Mr Papachristoforou.

"It's a huge field we must pay attention to," he said. "There will be a lot of surprising findings coming out of it."

- Published7 October 2011