CES 2012: 3D printer makers' rival visions of future

- Published

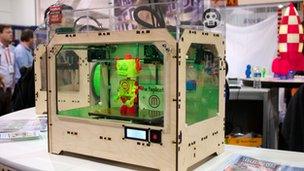

The Cube 3D printer could help you print your own toy shop

With a whir and a click the job is done. In the space of 20 minutes a plastic bottle opener has been constructed by the Replicator - a 3D printing machine capable of making objects up to the size of a loaf of bread.

The device is made by the New York start-up Makerbot Industries and was launched this week at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

The newly-created bottle opener feels warm to the touch and has to be prised away from its base.

It has been created by using extrusion technology - a process in which a spindle of plastic thread is unravelled, melted and fed through a print head which draws the object layer by layer - in this case at a rate of 40mm per second.

3D printing is nothing new - engineers and designers have been using it for more than two decades to create prototypes.

What has changed is that the printers are now being pitched at consumers.

Discount designs

The Replicator is being sold for $1,749 (£1,130) for the basic version that makes objects in one colour. An additional $250 buys a two-colour version.

Each spool of plastic sells for about $50 - enough to build a toy castle playset which would cost up to three times the price in a store.

"It's a machine that makes you anything you need," Makerbot's chief executive, Bre Pettis, tells the BBC.

"Handy in an apocalypse or just handy for making shower curtain rings and bathtub plugs.

"We want to get this into the hands of the next generation because kids these days are going to have to learn digital design so they can solve the problems of tomorrow."

Objects can be created on a computer using free online software such as TinkerCAD or Google Sketchup, before being transferred to the Replicator on a SD memory card.

Alternatively other people's designs can be downloaded from Makerbot's community website Thingiverse.

The site follows open source principles - any design uploaded to it must be shared for free.

"We get asked a lot: 'When will I be able to buy objects?' and I think that is a relic of consumerist lifestyles," says Mr Pettis.

"I would like to live in the future where somebody creates a digital design - maybe a great faucet handle - and after that nobody needs to recreate a faucet handle because it's been done. Or maybe if they want to make it a little bit different it or add their initials they can do that.

"But I don't think we need a marketplace. It's a sharing world. We are at the dawn of the age of sharing where even if you try to sell things the world is going to share it anyway."

It is a chilling thought for defenders of intellectual property rights who have already seen piracy take its toll on the music and movie industries.

Printing pioneer

Makerbot chief exec Bre Pettis says the printer could be used in space

Take a walk to the other side of the convention centre and you will find another plastic printer maker with another new product, but a very different way of thinking.

3D Systems is a North Carolina-based veteran of the business.

"We invented 3D printers," its Israeli-born chief executive Abe Reichental says.

"For 25 years we have taken the classic journey of taking expensive, complex technology and bringing it down in price.

"We have about 1,000 workers worldwide. We are a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange. We have almost as many patents as employees."

App store

The firm is at CES to publicise the launch of Cube, its first consumer-focused product.

The $1,299 device is smaller than Makerbot's but looks more user-friendly, utilising cartridges rather than spools of plastic thread.

It also boasts its own app store. The launch library includes software to customise belt buckles, a program to turn your voice into a bracelet design, and perhaps most excitingly software from developer Geomagic for Microsoft's Kinect sensor that allows the peripheral to replicate the user's face.

Work is also ongoing on an app to allow owners to use Kinect to sculpt objects by shaping their hands in the air.

Like Makerbot, the firm also offers other people's designs for download. But unlike its New York competitor it offers creators the chance to sell their goods in an online store. Designers keep 60% of the proceeds.

"Our philosophy is that we want to give an economic incentive to anybody to create and make in 3D, and we want to do it in a way that developers can monetise their creative sweat equity in it," Mr Reichental says.

"The bottom line here is that we think democratisation goes hand in hand with monetisation.

"The monetisation here is primarily for the benefit of accelerating adoption.

"We can't come up with all the possibilities and we don't think that the average person will stretch themselves as deep as they can if there wasn't a monetary advantage."

Tie-ups

3D System's booth resembles that of Makerbot in that it is covered with self-made playthings including dinosaurs, planes and chess pieces.

Owners of Makerbot's Replicator have free access to more than 10,000 designs

However, unlike Makerbot, 3D System's embrace of capitalism means that it is already in talks with established toy makers and other companies about the potential of selling access to their designs.

For the time being it stresses that the Cube's main purpose is to drive creativity.

"There are so many different ways that people are looking to harness the power of this new communication and expression tool," says Mr Reichental.

"Because that's what this is. It's really not so much about printing as it is about realising and making something real from an idea."

Eco-unfriendly?

3D Systems says it aims to bring the cost of its machine to below $500 over the coming years to drive take-up.

However, the mass adoption of such devices could have consequences for the environment.

While both firms offer corn-based PLA plastic consumables which biodegrade, they also sell ABS plastics - the type used to make Lego - which does not break down unless treated.

A generation of new designers testing and refining their designs conjures up images of mountains of 3D printed waste.

Yet neither boss appears unduly worried by the prospect.

"The amount of plastic we are talking here is not a lot and it is recyclable," says Mr Pettis.

"I would suggest that people focus on innovation and the ability to make whatever they need, and by all means if there are things you can make with the biodegradable ones then do it."

Mr Reichental offers a similar sentiment: "When we look at all the opportunity to improve the quality of life for the betterment of mankind then so long as we apply some discipline then I think it is a good thing."

Moon bases

3D System's more advanced printers can print plastics in determined "a pixel at a time" as well as in metals, nylons, powders and liquids - offering the prospect of a future in which home made devices can replicate any object Star Trek-style.

For the moment Makerbot notes that its Replicator is advanced enough to build most of the components necessary to reproduce itself.

Both firms describe their efforts as having "democratising" effects with the potential to change the world.

"We can put this power of creativity in the hands of kids - imagine how much more powerful when they reach adulthood," says Mr Reichental.

Abe Reichental believes offering developers the chance to earn money will spur on innovation

"This may be the last toy that they have to purchase because they can begin to create their own toys and become creative and innovative in their own right."

Mr Pettis' vision is even more radical.

"We're delivering on that dream of the future where you can have anything you want - you can download it on the internet and just have it manufactured in your house," he says.

"It's my goal to put Makerbots on the moon building the moon base for us.

"It's my hope that if an apocalypse happens people will be ready with Makerbots, building the things they can't buy in stores. So we're not just selling a product, we are changing the future."

- Published16 September 2011

- Published21 September 2011